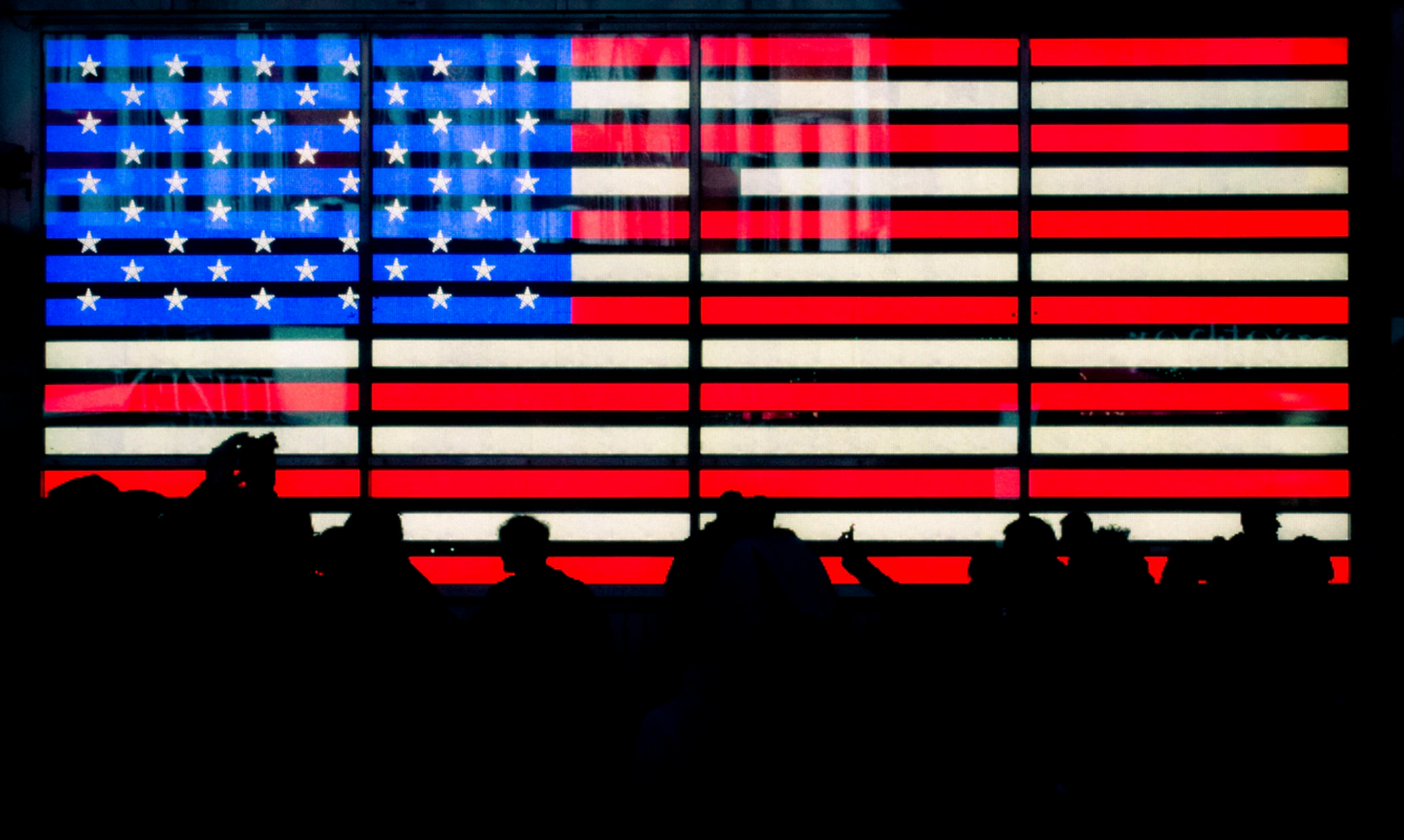

If 2020 taught us anything, it is that America is deeply divided.

In a year dominated by the COVID-19 pandemic, responses to the crisis diverged along party lines. Republicans more or less followed President Trump’s anti-mask messaging that encouraged Americans to ignore the virus, while Democrats more closely adhered to the public health guidelines which Trump flouted. Then, as America grappled with the murder of George Floyd and millions took to the streets to protest longstanding racial injustice and police brutality, 84% of Democrats supported such demonstrations while 50% of Republicans opposed them. Though Biden ran on the platform of reunifying a divided America — claiming that he would be a “president for all Americans” and making the theme of his inauguration “America United” — division over the election lingers. As of May 2021, six months after the 2020 election, 53% of Republicans and a quarter of all Americans felt that Trump was the “true president.”

Behind the headlines, partisans remained deeply divided with regard to their views on government and policy issues in general. As of an April 2021 poll, 36% of respondents who identified more with the Democrats trusted those in Washington to do what is right while only 9% of those who identified more with Republicans did. On policy issues ranging from climate change to foreign policy, in 2019 there was an average gap of 39 points between Republicans and Democrats’ responses to fundamental political value questions.

I argue that these public opinion findings reflect political polarization, the buzzword of our political era. While political polarization is not a new concern, it has risen dramatically over the last 25 years, and it feels as if that increase came to a head in 2020. One cannot turn on the TV or scroll through their social media feed without being bombarded by pundits and politicians alike decrying this polarization, invoking the same statistics from above. Hence, given the omnipresence of political polarization in contemporary American life, I can hear the reader at home silently ask themselves why reading a recap of the divisive issues of 2020 is constructive, and more broadly why a column on political polarization — the project I am embarking on here — is needed. After all, isn’t everyone sick of hearing that we are divided?

I know I am. But, I am more sick of hearing that we are divided without scratching the substantive surface of why, of hearing that we are divided without seeing work done to rectify that division by the politicians and pundits who decry it.

Americans always have been, and always will be divided. We are the United States of America because the individual states wouldn’t have survived without banding together at the time of our founding, not because there was agreement amongst the states on how to form a government. Fast forwarding to today, the notion that 330 million people with vastly different lived experiences could agree on much, if anything, seems impossible to me. And, every American should not agree on every issue; if that were the case, we’d be living under the tyranny of the majority that Hamilton, Jay, and Madison decried in the Federalist Papers of our founding.

Thus, I don’t see the lone fact that we are divided as an issue. Rather, the issue is the state of our division. Our division is one that is contentious and filled with animosity, separating families and friends across the country. Our division is one wherein both sides are so entrenched in their side — and their own reality — that moments of compromise are increasingly hard to find, sending the notion of “E Pluribus Unum” — “Out of Many, one” — into the wind. Our division is one that is destructive, both to American lives and institutions.

I opened this article with the notion that if 2020 taught us anything, it is that America is deeply divided. But 2020 did more than that — it also taught us that this division has the potential to be incredibly dangerous. Our division over COVID-19 has contributed to over 500,000 deaths as the American public was — and continues to be — unable to uniformly confront the pandemic, with mask wearing and vaccination becoming a political statement. Our division over George Floyd’s murder and subsequent protests allow inaction on addressing police brutality, perpetuating discrimination and racism in our country. Our division over who won the 2020 election is what likely led to the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, which 84% of Democrats say was “an attack on democracy [that] should never be forgotten” while only 18% of Republicans agree.

Given how pernicious our division is — and I emphasize “our” because we all contribute to it, all have ownership over it — we must all make an effort to understand it. Understanding why we are divided is a prerequisite for unifying, not even on political issues but rather, simply, as Americans. This is no easy task. The polarization which plagues our nation is a massive and complex political and social problem, and it requires a great deal of unpacking.

Like any political and social problem, political polarization has many causes, from rising economic inequality and the evolution of new media technologies to particularly polarizing political actors and broader political movements like the southern realignment. Like any political and social problem, political polarization has many effects, from gridlock in Washington and at Thanksgiving Day tables across the country to the events of 2020 that I’ve discussed throughout this article. And, like any political and social problem, scholars, politicians, and we the people contest these causes and effects and question the magnitude, nature, and implications of polarization.

Political polarization, the hot-button issue of our day, is paradoxically nebulous because of its complexity and enormity. While this characterization is daunting, we must step by step work to detangle this issue. 2020 taught us we’re divided. It also taught us that that division is dangerous, for Americans and their democratic institutions. 2020 brought — and continues to bring — pain to so many Americans; and our nation is nowhere near being healed. But, we are at the turning point, the moment when the smoke is starting to clear and we can meaningfully reflect on the lessons we learned from 2020 while still feeling their weight. We are living in the moment when we have a say in how we heal, in how we rebuild, in how we forge a new path forward — a path that should aim to open communication channels between partisans and restore constructive dialogue so that we take subsequent steps together. To determine the starting place of this path, I hope you join me on my tour of The Polarized State of America — after all, everyone loves a good summer road trip.