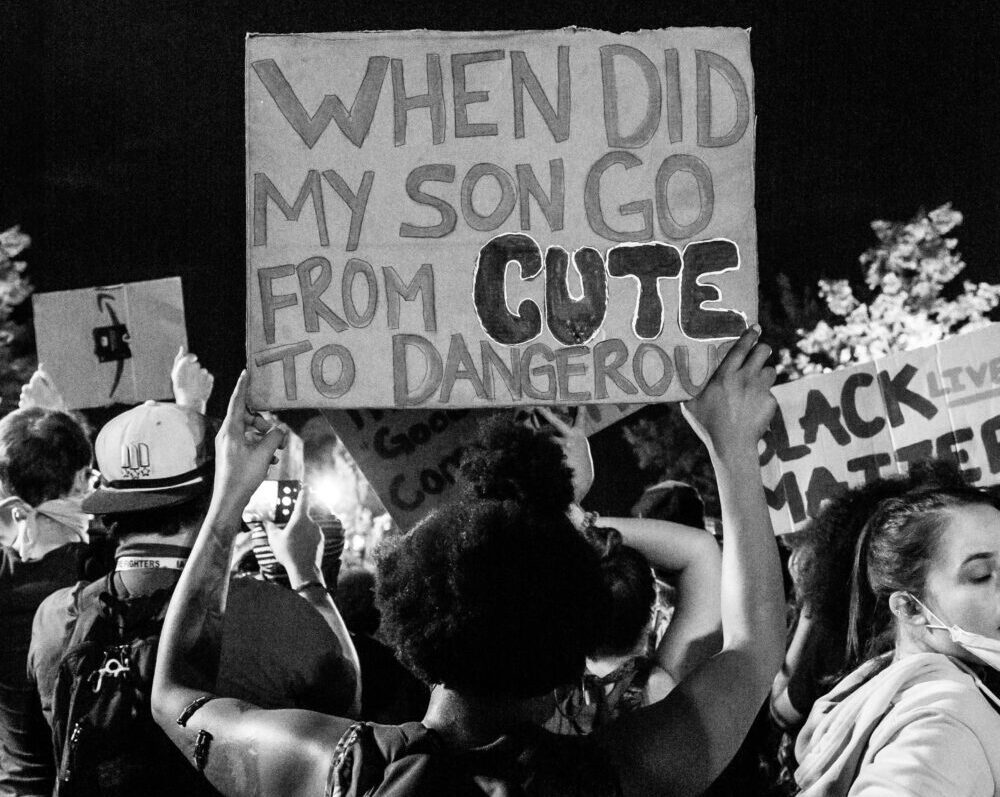

America stands at a crossroads, haunted by the specter of its history as it confronts the recent loss of two innocent Black men — Marcellus Williams and Freddie Owens — through state-sanctioned executions. These tragedies are not isolated incidents, but vivid reminders of a legacy of racial injustice that continues to poison the well of our national conscience. Many wish to sidestep discussions about race, believing we should have moved beyond these issues because of the “progress” we’ve made. Yet, when innocent Black lives are extinguished by the very systems meant to protect us, it becomes painfully clear that we cannot simply “get over it.” These men could have been my father, my brothers — or even me.

The executions of Williams and Owens are modern manifestations of a brutal past — a time when lynchings were not only tolerated, but often sanctioned by the state. From the late 19th century well into the 20th, lynching was a gruesome practice used to enforce White supremacy and instill terror within Black communities. These acts were public spectacles, grotesque performances intended to uphold a rigid racial hierarchy. Perpetrators operated with impunity, fostering a culture where violence against Black people was both socially accepted and legally ignored.

In 1972, the Supreme Court invalidated the death penalty, noting that it resembled “self-help, vigilante justice, and lynch law.” The Court, in its ruling in Furman v. Georgia, stated that the criteria used to impose the death sentence appeared to be influenced by race, which the court ruled constitutionally unacceptable. Southern legislators condemned the Court’s decision. Advocates for Georgia’s revised law demanded that “there should be more hangings. Put more nooses on the gallows. We’ve got to make it safe on the street again.” In 1976, the Supreme Court upheld Georgia’s death penalty statute, reaffirming the application of capital punishment and the racial disparities it perpetuates.

The story of George Stinney Jr., a 14-year-old Black boy from South Carolina, embodies this dark chapter of our history. In 1944, Stinney was wrongfully convicted of murdering two White girls after a trial that barely lasted two hours, with a jury composed entirely of White men. He was executed by electric chair, becoming the youngest person executed in the United States in the 20th century. Seventy years later, his conviction was vacated, with the presiding judge acknowledging the grave injustice inflicted upon an innocent child. George Stinney’s case is a haunting reminder of how the machinery of the state has been wielded against Black lives — a pattern that alarmingly persists today.

Today, the death penalty stands as a vestige of this violent history. It is a state-sanctioned mechanism that disproportionately targets Black Americans, perpetuating a cycle of injustice under the guise of lawful punishment. Studies consistently show that Black defendants are more likely to receive the death penalty, especially when the victim is White. Black Americans represent 41% of those on death row and 34% of those executed, despite accounting for just 14% of the overall population. This disparity is not a mere coincidence, but a stark indicator of systemic biases deeply entrenched within our judicial system. The executions of Williams and Owens, despite significant doubts about their guilt and the fairness of their trials, underscore the perilous intersection of race and capital punishment.

Marcellus Williams was convicted of a 1998 murder in Missouri, even though DNA evidence later suggested he was not the perpetrator. Despite this compelling evidence, the state pressed forward with his execution, disregarding the fundamental principles of justice it claims to uphold. Freddie Owens faced execution in South Carolina amid serious questions about his innocence, his mental health, and the adequacy of his legal representation. In both cases, the state’s relentless pursuit of the ultimate punishment, despite profound uncertainties, reflects a disregard for Black lives disturbingly reminiscent of the era of lynching.

The death penalty carries the irreversible risk of executing the innocent — a risk that disproportionately threatens Black individuals due to systemic racial biases. The finality of death leaves no room for rectifying miscarriages of justice, making the stakes impossibly high in a flawed system. Cases like those of Nathaniel Woods, Dustin Higgs, and Troy Davis highlight the irreversible consequences of capital punishment when doubts persist about the guilt of the defendants or the fairness of the trials. Despite controversies surrounding their convictions and claims of innocence, their executions eliminated any possibility for their exoneration if new evidence was to emerge. The moral and ethical implications of this reality are profound and demand our immediate attention.

Abolishing the death penalty is not merely a policy decision; it is a moral imperative rooted in the recognition of our shared humanity. It compels us to confront the uncomfortable truths about our history and the ways in which they continue to shape our present. By eliminating capital punishment, we take a crucial step toward dismantling the remnants of a legacy that has long sanctioned the taking of Black lives with impunity.

We must also address the broader systemic issues that allow such injustices to persist, particularly those enshrined in specific policies like stop-and-frisk, which disproportionately target minority communities, and the cash bail system, which incarcerates low-income individuals pre-trial due to their inability to pay. This involves reexamining laws like mandatory minimum sentencing, which strip judges of discretion and often result in harsher penalties for minorities, contributing to racial disparities in the criminal justice system. By confronting and reforming these procedures, we can begin to dismantle the biases that undermine fairness and equality for all citizens.

The discomfort some feel when discussing race reflects a deep-seated denial that hinders progress. Ignoring these issues does not erase them, it perpetuates them. According to a February CBS News Poll, around 40% of Americans feel uncomfortable talking about race, reflecting widespread unease across various demographics. This discomfort often stems from concerns about potential criticism, misunderstanding, or offense to others during these sensitive discussions. As society continues to grapple with racial issues, this statistic highlights the need for more open and empathetic conversations about race in America. True reconciliation and healing can only occur when we collectively acknowledge and address the systemic injustices inflicted upon Black communities for generations.

The deaths of Marcellus Williams, Freddie Owens, and George Stinney Jr. are not just individual tragedies: They are stark reminders of the unfinished work that lies before us. We owe it to them, ourselves, and future generations to confront these injustices head on. By abolishing the death penalty and committing to systemic reform, we honor their memories and move closer to a society that truly embodies justice and equality for all. Silence and indifference are luxuries we can no longer afford. The stakes are too high, and the cost of inaction is measured in lives lost and communities devastated.

We can’t “get over” the issue of race in America because, in truth, it has long since gotten over us — entrenched in our systems, embedded in our laws, and ingrained in our collective consciousness. The tragic executions of Marcellus Williams and Freddie Owens are not aberrations, but the grim echoes of a history that refuses to fade. As long as the specter of racial injustice looms large, casting its shadow over the very fabric of our nation, the idea of moving past these issues is not just naïve — it’s impossible. We cannot heal what we refuse to confront. If we do, the cycle of injustice will continue, haunting us all.