When I was in middle school, I felt like a man.

While nothing about my physical appearance conveyed masculinity, I didn’t feel like I measured up to the standards of femininity to identify as a woman. I associated femininity with beauty, and if I couldn’t see myself as beautiful, I couldn’t see myself as feminine.

In retrospect, I realize it was overly reductive to base my womanhood on how physically attractive I was, but, in some ways, that mentality persists. I often hear the words “I look like a man” escaping the mouths of my friends. What they mean to say, I think, is that they don’t look their best. Perhaps this is why I gravitated toward traditionally feminine things: skirts, dresses, and the color pink: I was compelled to overcompensate for my masculine inclinations by presenting hyper-femininely.

It’s the classic “sit still, look pretty” trope: the notion that my physical appearance is my most salient characteristic. Of course, no one in my close circle is actively pedaling that narrative — it’s been instilled in me through societal conditioning.

I’m in an environment where I don’t have to conform to a specific path: I can forge my own. However, the definitions of an empowered woman are narrow. If you’re not breaking boundaries in your career, you’re not empowered. This point of view is very dichotomous. You’re either a dedicated, aggressive, and progressive woman, or you’re complacent.

Women who dedicate their lives to their families are labeled as such. They are said to perpetuate an archaic view of women. Liking pink, dressing provocatively, or listening to degrading music are other characteristics of women likely to garner the label of complacency. When you’re complacent, you impede progress for women. You are a bad feminist.

I fall into this stereotypical category. I still love the color pink, dresses, flowers, and other traditionally feminine things. I often feel pressured to eviscerate my traditionally feminine characteristics to be progressive.” Isn’t it counterintuitive to suggest that to free women, you must restrict them? It eliminates women’s agency over their very character.

Men have been regulating women’s behavior for centuries, and now women are too.

These ideas are best espoused by writer Roxane Gay in her collection of essays entitled “Bad Feminist.” Gay expresses that the problems with feminism often stem from how it creates a monolith based upon its loudest voices. The concept of a feminist archetype excludes women who lie outside the boundaries drawn. However, she also warns that the problem isn’t necessarily with the feminism movement but rather with the voices that we have grown to associate with it. We take the biggest personalities, and we let them speak for a group that encompasses a wide array of people.

However, feminism is personal and subject to individual interpretation. There can be no ideal feminist. There is no one way to behave that can be considered aligned with feminism. I agree with Gay when she writes, “I believe [that] feminism is grounded in supporting the choices of women even if we wouldn’t make certain choices for ourselves.”

The only way for women to be truly equal is when they don’t have to conform to a specific character to be considered equals. Discriminating against traditionally feminine characteristics reinforces the perception that femininity isn’t good enough. It implies that you have to become masculine to succeed and thrive. In fact, I would argue that in order to achieve true equality, you must stop considering certain traits as feminine and others as masculine. This binary accentuates and further exacerbates the difference between women and men, making equality ever more distant.

Are men and women actually that different? Both men and women can exhibit characteristics typically classified as masculine or feminine. Differentiation of specific features makes them off-limits to the other gender.

Due to this, I often felt as though I didn’t belong within the constraints of one gender over others. I thought for a while that I might identify as non-binary. I didn’t dislike being a woman, and I certainly didn’t feel like a male. I just felt limited under the label of female.

I struggled with discerning whether this feeling stemmed from any aspect of being female or from my own understanding of the female gender identity. My conceptions of femininity didn’t necessarily have to be its end-all definition. My only constraint was mental.

Maybe I could be anything I wanted to be and still be female. Maybe gender was irrelevant to my actual personality. I needed to stop comparing myself to idealized constructs of femininity. Women can be anything that we want to be. We don’t have to be subject to any man — or woman — telling us who we are.

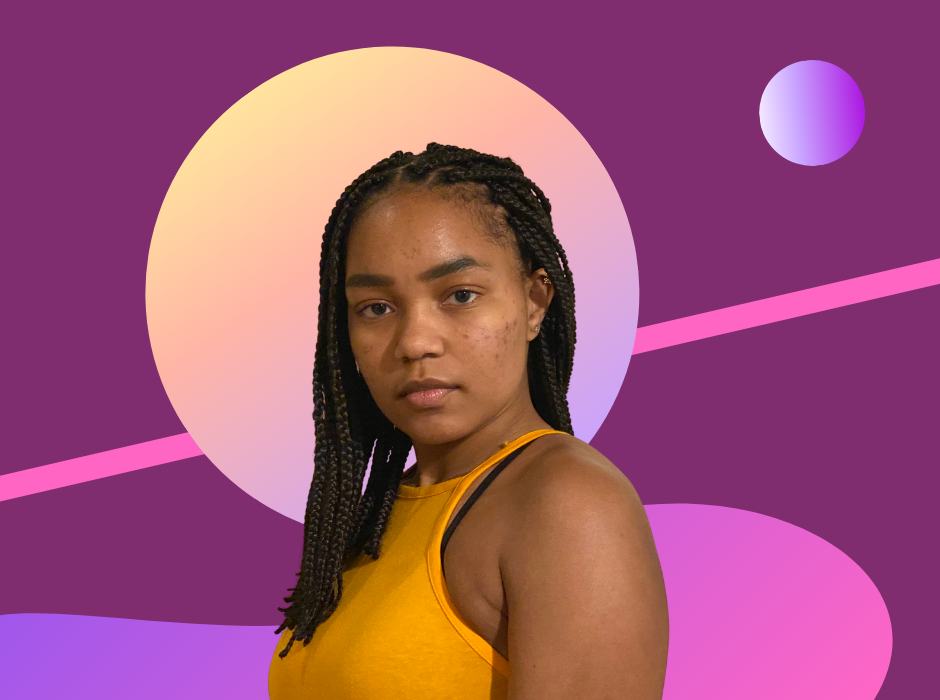

The original artwork for this article was created by Harvard College student Duncan Glew for the exclusive use of the HPR.