This year, my eighteenth birthday was marked not by candles and celebration, but rather by a whirlwind move across the country from California to Cambridge. While I felt tremendous excitement about my first semester at Harvard, I was also apprehensive — not only about typical pre-college anxieties — but also about my first time voting away from home.

On September 14, California held a special election to consider whether or not to recall Governor Gavin Newsom. In the weeks leading up to the election, I struggled to navigate the notoriously fraught out-of-state voting process.

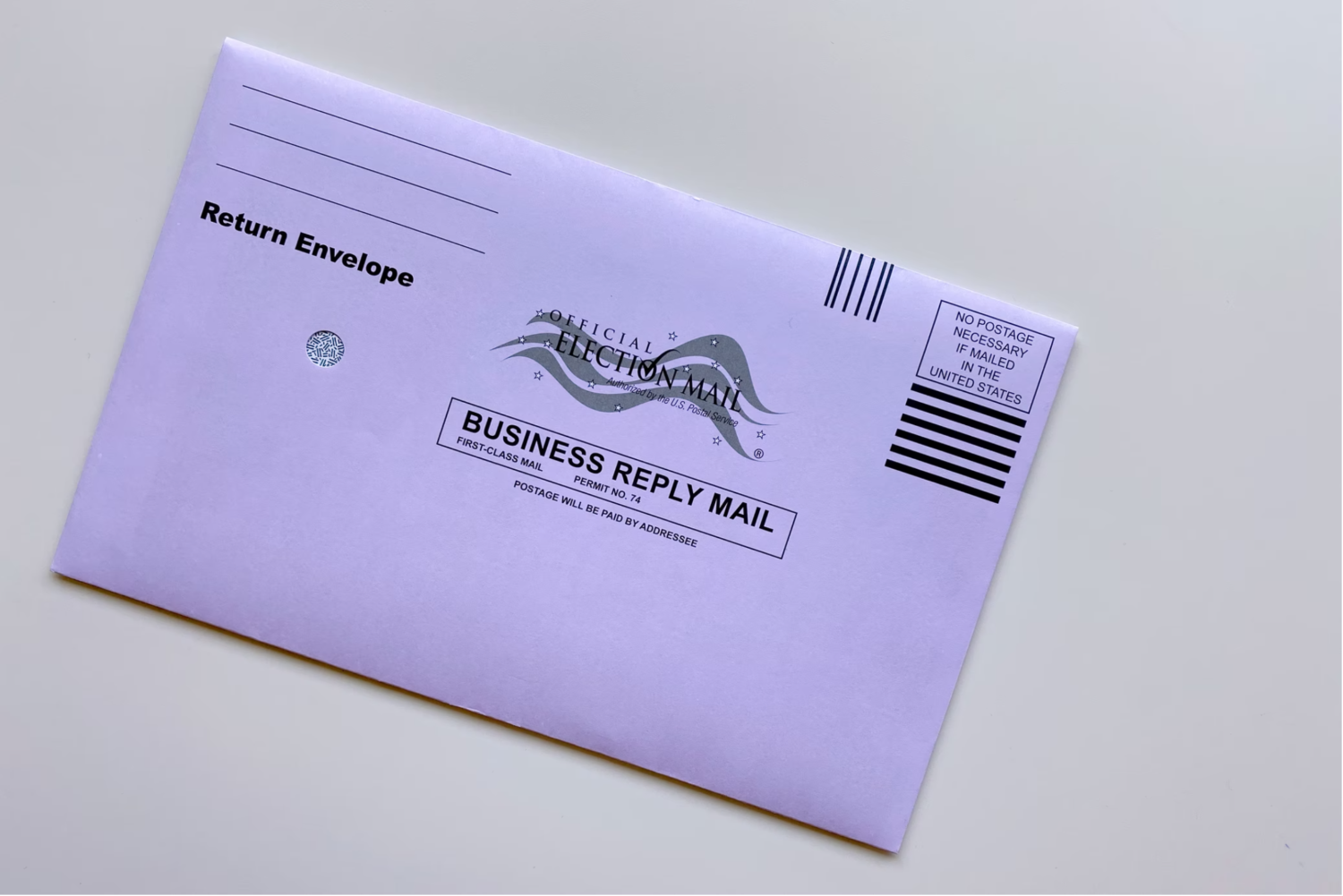

I finally managed to register to vote and request an absentee ballot two weeks prior to the election, but the Harvard Yard Mail Center did not process my ballot until Monday, September 20, nearly a week past the deadline. As a result, I was not able to vote in my first-ever eligible election.

This experience represents an unfortunate casualty of Harvard’s infamously decentralized mail distribution system. In the wake of a wave of historically significant local and statewide elections, now is the time for Harvard to update its mailing sorting system to expedite the delivery of absentee ballots.

College undergraduates have significant voting power. If it is harnessed effectively, students have the potential to influence election outcomes nationwide. There are nearly 20 million undergraduates, yet millennials have the lowest voter turnout rates out of any generation. For example, despite the best efforts of initiatives like the Harvard Votes Challenge, as of 2016, only 77.6%of Harvard’s undergraduates were registered to vote, and merely 57.8%of students actually cast their ballots in the presidential election.

So why is voter turnout so low among college students?

Many have attributed this phenomenon to a lack of interest or sense of civic engagement among young people, but in reality, this is not only a result of voter apathy. Instead, the significant obstacles and inconveniences intrinsic to voter registration and ballot-casting while in college inhibit college students from accessing the polls — a phenomenon many experts have likened to large-scale voter suppression.

Although all states require voters to be residents prior to casting a ballot in that state, different states have different requirements for authentication. For example, states like Iowa and Tennessee require voters to show proof of residency, like a utility bill or a mortgage statement — documents that college students who reside in on-campus dorms would likely not have.

Furthermore, other states like North Dakota and Arizona mandate that voters show a government ID that displays their permanent address. However, many students do not have driver’s licenses, and for those that do, their licenses display their hometown addresses, not their college residence’s state.

Nationally, student turnout in the 2016 presidential election was greater that of 2012, but it dropped dramatically in the state of Wisconsin during the first year that its statewide voter ID law applied to college students.

However, barriers to student voting extend far beyond swing states like Wisconsin. For instance, many voter ID laws in solidly blue states like Massachusetts also do not accept college student ID cards or out-of-state driver’s licenses as valid forms of voter identification.

This patchwork of voter residency laws and identification requirements results in confusion, particularly for first-time voters, constricting civic engagement and driving down voter turnout among undergraduates.

Research has repeatedly demonstrated that when voting procedures are more convenient, voter turnout increases. While there is no one reason for low voter turnout, evidence suggests that obstacles to college students voting have significantly contributed to its decline.

When trying to vote from campus, out-of-state Harvard students will likely encounter the hassles of providing proof of residency, deciphering absentee ballot procedures, and unraveling complicated voter identification policies. With substantial roadblocks to voter access already in place for college students across the country, Harvard should not exacerbate this issue by subjecting voter documentation to HYMC’s mail delivery bottleneck.

This is by no means a critique of the HYMC employees. They are charged with the formidable task of sorting the mail of over five thousand undergraduate students, and they must do so within the confines of a system they did not design. Harvard’s mail distribution problems are clearly structural, and thus, they demand structural solutions.

With the 2022 midterms on the horizon, Harvard should update its mail sorting system to accelerate the processing and delivery of absentee ballots and other voting-related documents. Doing so will ensure that every student who wishes to vote is not hindered from political participation, thereby fortifying Harvard’s institutional commitment to civic engagement and fostering a positive voting experience for its undergraduates, many of whom will be participating in this civic process for the first time next November.

HYMC may be able to mitigate voter suppression on Harvard’s campus by reconstructing its mail delivery system to expedite the sorting and delivery of absentee ballots, but the University can do much more to combat college voter suppression on a national scale. As an institution with tremendous influence over the political sphere both in its status as a prestigious university and in the graduates it produces — many of whom go on to occupy powerful political seats — Harvard alleviating voting barriers for its undergraduates would mark a substantial turning point in how academic institutions more broadly prioritize civic engagement. By taking an active stance against voter suppression, Harvard can truly uphold its institutional commitment to producing “the citizens and citizen-leaders for our society.”

Image by Tiffany Tertipes is licensed under the Unsplash License.