It seems as though everybody has an opinion on consulting. Collegiate rhetoric boasts an abundance of opinionated vocabulary describing the industry and those who choose to enter it, with phrases ranging from “corporate snakes” to “climbing the ladder.” The issue of consulting, however, is understandably not so simple. Whereas some Harvard students lambaste the ethical atrocities of Wall Street, others call into question discrepant degrees of privilege, and the consequent range of priorities in pursuing a post-graduation career.

Despite its contested nature, consulting continues to attract rising numbers of undergraduates with each passing year. Though the complete explanation behind such an increase is likely complex, the personal insights of students help clarify the phenomenon. For some, the promise of rigorous problem-solving and client interaction aligns with their original vision of an ideal occupation. Others admit they want a plush job with handsome pay. Another, often under-discussed undergraduate reality is that of low-income students, many of whom enter the consulting profession due to a combination of personal choice and financial necessity.

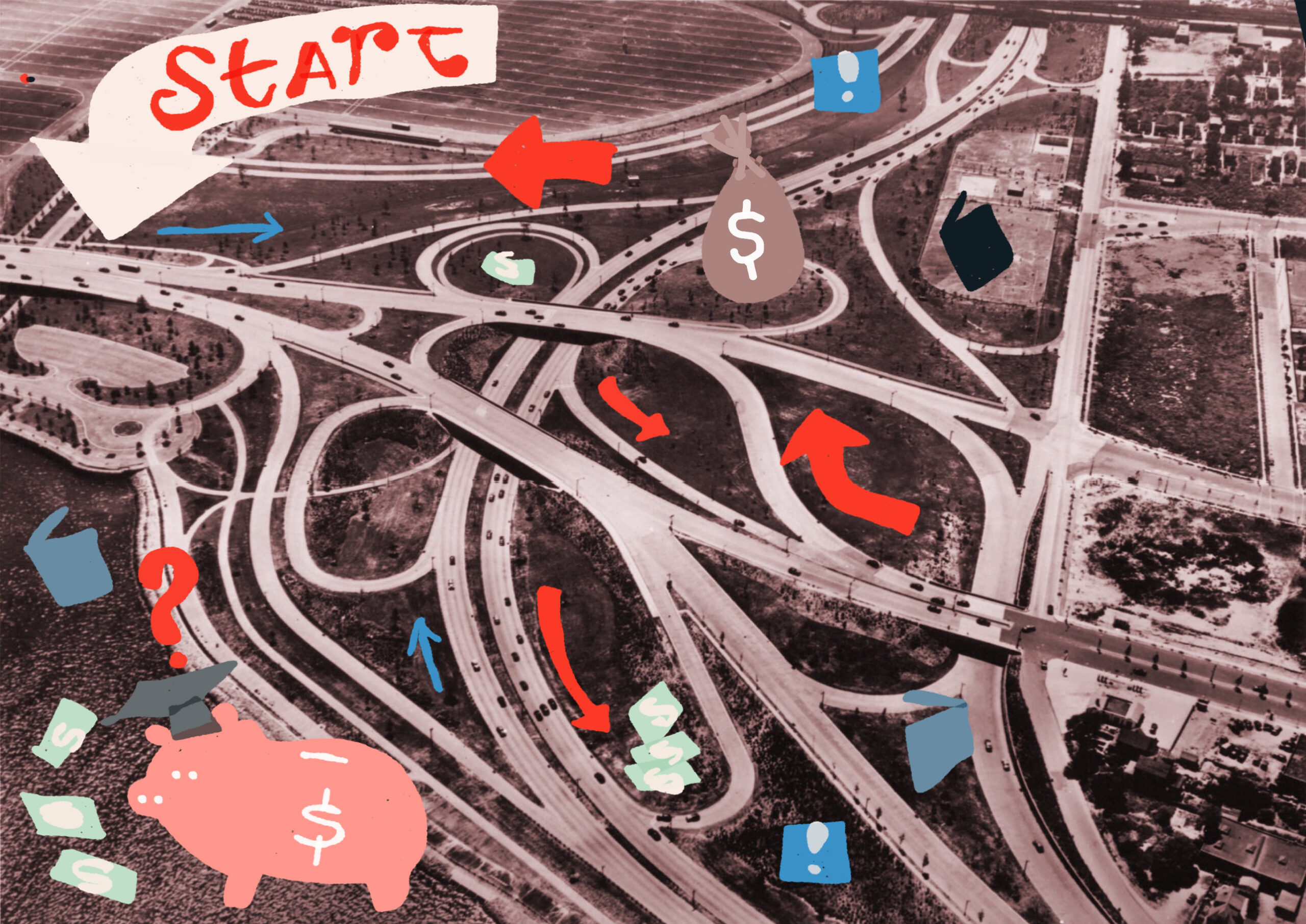

The variable of higher education further complicates this already convoluted equation of careerism, corporate fascination, and familial obligation. Why have institutions of higher learning, particularly Ivy League universities, become breeding grounds for corporate excellence and managerial prowess? Can this trend ever be compatible with Harvard’s lofty vision of a holistic liberal arts education? Or has such a model become an entitled delusion in our increasingly competitive status quo, one where incoming freshmen are already finalizing the blueprints of their lives?

The Profits of a Liberal Arts Education

“Before you can change the world,” Harvard asserts on the “Why Harvard” section of its Admissions & Financial Aid page, “you need to understand it.” Intellectual curiosity and individualistic courage are prized possessions at the undergraduate level, made amply clear by this portion of the University’s website, which claims that “Harvard’s liberal arts and sciences philosophy encourages you to ask difficult questions, explore unfamiliar terrain, and indulge your passion for discovery.”

How precisely does consulting — an occupation which broadly calls on analysts to advise individuals and businesses by devising solutions to a problem — interact with this idealized understanding of a liberal arts education?

Top management consulting firms are quick to advertise their services as indispensable to successful people belonging to successful companies. McKinsey & Company promises to “combine global expertise and local insight to help [clients] turn [their] ambitious goals into reality,” while Bain & Company contends that it assists clients to “achieve results that bridge what is with what can be.” Boston Consulting Group similarly proclaims itself as “[partnering] with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities.”

Despite the appealing definitions, some Harvard undergraduates are convinced these descriptions could not be further from the truth. What strikes first-year Michael Evans ’24 as particularly concerning, for instance, is the absence of individualistic creativity certain consulting responsibilities possess. “What are you innovating on yourself, what are you trying to build?” Evans asked. The confusion in his voice was palpable over the phone.

Confusion develops into concern for Evans when considering the undergraduate opportunities lost to the hands of consulting. “I think it’s really sad that a lot of the intellectual capital from top-tier universities is going there,” he told the HPR. “Harvard, I believe, has enough people to completely change the world.” Even with the pandemic restricting a vast majority of social interactions with fellow students, Evans said he has met “so many incredible people” in his first two semesters alone: “If we all decided to get something done, I think it could happen.”

Why, then, do the statistics continually point towards the opposite trend? In 2019, the University’s Office of Career Services reported that 13% of graduating seniors would enter financial services upon graduation and 10% consulting, compared to 5% in healthcare or medical services and 2% in both education and law/legal services. That same year, The Harvard Crimson’s annual “By the Numbers” feature reported a greater inclination toward those first two fields, with 18% of graduating seniors entering consulting and 17% finance. The following year, those numbers only rose; The Crimson published that 23% of graduating seniors entering the workforce were headed to the finance sector, with consulting following close behind at 22% and categories including public service/nonprofit, arts, government, and law each attracting a dismal 3%.

When extrapolating potential trends from these numbers, it is important to consider the limitations of student surveys and dynamic post-graduation plans. As explained by the Office of Career Services, the data published is a “snapshot of where students find entry-level opportunities at graduation, rather than a complete representation of what they end up doing later on after acquiring advanced skills through training.” In interviews with the HPR, members of the Office also questioned the representativeness of The Crimson’s sample size. Still, the percentages point towards a convincing trend of students gravitating towards finance and consulting, two pathways commonly perceived as lucrative.

One explanation for the growing undergraduate intrigue surrounding corporatism may lie in the dissonance between Harvard’s exterior identity as a champion of intellectual curiosity and the interior, often unspoken pressure among students to prioritize perceived status over knowledge. Evans describes the institution’s incentive structure as fundamentally “misaligned,” a system which routinely rewards individuals who fixate on particular high-paying industries which wield the brunt of financial and political power. “People end up being unrightfully drawn to careers that don’t really serve the best interests of society and themselves,” he argued.

Another hypothesis, as explained by a post in the Harvard Confessions Facebook page — an online platform dedicated to publishing anonymous, candid ruminations of Harvard students — suggests that the college’s hyper-competitive admissions process often motivates high schoolers to groom themselves in an overambitious and commonly disingenuous way. “Big assumption to think that the ‘intellectual curiosity’ the admissions office sees is usually real,” the post reads. “Prep schools are paid tons of tuition to create fake intellectuals who can dazzle ivy league officials with eNrIcHiNg ExPeRiEnCeS that they can drop once they’re admitted.” Rather than access their Harvard education as a window into increased academic rigor and personal growth, undergraduates are faced once again with the browbeating charge of progressing up yet another ladder — whether that be social, financial, or professional.

The anonymous user further contends that this socialization and subscription to conventional interpretations of success muddy an authentic impulse to foster meaningful change. “I think lots of Harvard people who enter finance/consulting do genuinely want to change the world but believe that those jobs are the only realistic options because they’ve been socialized to wealth and prestige,” the user wrote. “They’ll get the money and status to secure their family’s generational wealth then move into non-profits to feel better about themselves.”

Harvard undergraduates are not the only individuals questioning the social efficacy of consulting. Daniel Markovits, a professor at Yale Law School and the author of The Meritocracy Trap, argues that although individuals such as Pete Buttigieg — who himself entered the McKinsey & Co. after graduating from Harvard College — may blur the line between public service and consulting, technocratic management has played a “central role … in fueling the enormous economic inequalities that now threaten to turn the United States into a caste society.” Markovits writes that progressive thinkers assert American democracy “cannot be rejuvenated by persuading elites to deploy their excessive power somehow more benevolently.” On the contrary, certain members of the left contend that such a rejuvenation “requires breaking the stranglehold that elites have on our economics and politics, and reempowering everyone else.”

In fact, historical evidence suggests that management consulting is elitist by its very design, and has inflated the already disproportionate authority of top executives at the expense of middle- and lower-level management. As consulting firms bolstered their advertising efforts in prominent newspapers including The New York Times and TIME, they also increased layoffs, particularly targeting lower-level employees. In other words, exclusivity was becoming an intrinsic part of the operating system of these already selective firms. Markovits wrote that companies, some of which had historically embraced “no layoff” mentalities, began to “[downsize] in response not to particular business problems but rather to a new managerial ethos and methods; they downsized when profitable as well as struggling, and during booms and well as busts.”

The dubious ethics of top consulting companies’ operational landscape are not limited to their frequent slights of lower-level employees. In a March 2021 piece titled “McKinsey’s partners suffer from collective self-delusion,” The Economist argued that the absence of concrete metrics of competency made room for more questionable or “squishy” factors, or what Andrew von Nordenflycht of Simon Fraser University identifies as “social and personal characteristics” in his evaluation of how clients evaluate the competency of their consultant hires. In their Harvard Business Review article titled “Consulting on the Cusp of Disruption,” Clayton M. Christensen, Dina Wang, and Derek van Bever contend that “professionals’ education pedigrees, eloquence, and demeanor” regularly act as “substitutes for measurable results,” providing already prominent firms an additional competitive advantage. “Price is often seen as a proxy for quality, buoying the premiums charged by name-brand firms,” the article reads.

Such methods of measuring consultants’ aptitude and the success of their services portray a disconcerting trend in which individuals are handpicked for their possession of elitist characteristics, rather than actual critical thinking or problem-solving skills. For this reason, David Vega ’24 approached consulting with skepticism during his first year at Harvard. While the occupation was hardly a well known career choice among his high school peers, Vega realized that his Harvard peers regarded the industry with heightened seriousness, often even as an economic or pragmatic necessity.

“When I got to Harvard in the fall, I began to see that it really became less of a fallback,” Vega told the HPR. “I wouldn’t say it became a job by which people were really trying to go into — it seemed like something people just kind of fall into.”

Though Vega recognized that many undergraduates’ financial realities could not accommodate a career that may encourage more creativity but necessitate more risk, he could not help but predict a concerning trajectory for institutions of higher education. His disquietude was principally focused towards top-ranked universities such as Harvard, Yale, Stanford, and MIT which Vega defined as “incubators” for the future. “What tends to occur time and time again is that consulting almost becomes this mental handicap that prevents people from thinking creatively enough or taking enough risks to enhance something either in broader society or within themselves,” he said.

Vega identifies Harvard undergraduates’ transactional relationship with their collegiate education as a decisive explainer of the consulting craze. In the past several decades, according to Vega, there has been a “drastic” cultural shift in the way young people relate to institutions of higher learning in the United States. “There’s become a broad understanding of university as training for a job,” Vega said, despite the fact that these institutions are “not particularly well-tooled” to handle the responsibility. “I think a lot of first-years come in, and off the bat are looking for what will be their job that upcoming summer between freshman and sophomore year, what would be their job the summer after, and then eventually after four years of college,” Vega argued. “From day one, they’re trained to think that a job is the existential purpose of a university.”

A Glimpse Into the Low-Income Student Experience

“I’m a humanities/arts person, always have been. I’m also a first generation, low income student,” a user on Harvard Confessions wrote. “While in the past, especially on campus, I’ve gotten carried away in my concentration and convinced myself that I’ll be employable and will have a good income after college, this pandemic has really made me question that.” The student could not bear to think of their mother — a housekeeper and the family’s sole income earner — “working, doing physical labor and putting herself at risk anymore,” and wrote they were seriously considering reorienting their concentration and career paths.

Citing siblings back at home who had yet to attend college, the undergraduate admitted they felt “selfish” for pursuing their personal passions when they knew that the large sums earned at a firm had the capacity to alter their family’s livelihood. “I don’t know if I can justify to myself studying art and humanities anymore,” the user wrote. “I love all of my friends who study this, but they’re all wealthy and privileged. I’m starting to come to terms with the fact that maybe this happiness wasn’t meant for me but for my kids. I really don’t believe that I can afford to be an artist or a historian, but maybe in the future my kids will.”

Another anonymous student who identified as FGLI explained that they were “Just trying to climb the socioeconomic ladder and give [their] family a better life,” and expressed frustration over advantaged students who criticized their peers for entering into more profitable industries. “Check your privilege before you shame people for their career choices,” the post read. “How virtuous of you who were born into a rich family to shame those who want to give their kids what your parents gave you.”

Calvin Duran ’21, founder of Harvard Undergraduate Latinxs in Finance and Technology (LiFT) and an incoming associate consultant at Bain & Company, said that consulting is “definitely a well-worn path,” both extracurricularly and post-graduation.

“When I got to campus, there was a buzz around consulting, but being first-generation, low-income, I had no idea what the word actually meant,” Duran told the HPR. “I think that also prompted exploration on my end as well as a lot of curiosity from a lot of my peers who are in similar positions.” To add to the initial fascination, Duran described many of the on-campus consulting groups as being known for their “big social activities,” such as fancy formals.

Still, Duran confronted strong skepticism and often vocal criticism about the industry that challenged its intrigue. Duran told the HPR that it is common for students to refer to those involved in consulting as “sellouts” or “snakes,” and assume that prospective analysts only “want to get money out of [their] Harvard education.” As a first-generation, low-income student, Duran said, this attitude makes him feel “uncomfortable.”

“I feel that a lot of times in first-generation, low-income communities you have this expectation to give back in a very direct way, through public service or activism. Those are all things I think are very valuable and I care about,” Duran said. “But the reality is that my family’s poor, and I came to Harvard to increase my income earning potential, and so sometimes I feel as though those comments aren’t realistic or helpful.”

The disparate degrees of privilege among Harvard students was another critical factor Duran identified as a complicator of the consulting conversation. “Obviously, a lot of times the Harvard student body reflects a much higher average income than the entire United States. So it’s very easy to just write off people’s intentions as just, ‘Oh, they just want to get rich, they’re snakes,’” Duran told the HPR. “But there’s people here who have very real reasons for going into consulting.”

For those who are not familiar with the industry, Duran said that consulting can be a “really vague concept.” Duran continued that the “big learning curve” that accompanied the recruiting process “dissuades” undergraduates from trying, particularly those who belong to underrepresented minority groups. “The whole case interview, having to have done your networking, and even a requisite to get into a place like Harvard which is already very selective and already requires a learning curve — it’s almost this whole, entire other process that you have to navigate. The fact that so many accomplished people are undergoing that process and investing that time and effort can seem really intimidating.”

The expedited consulting recruitment process, Duran added, was another aspect of the industry that could easily render it inaccessible for students. By the time large firms were launching their recruitment cycles for diversity programs in his freshman and sophomore year, Duran was “still trying to navigate Harvard,” and “still trying to overcome the insecurities of trying to fit in, who [he] was, what [he] wanted to do, let alone trying to toss [his] hat into this even more unknown, far-off application process.”

Despite these initial barriers, Duran expressed appreciation and gratitude for his upperclassmen mentors who provided much-needed insight, perspective, and support throughout his personal entry into the industry. “I was really fortunate to have a lot of supportive people — and people who came from similar backgrounds and had successfully navigated the process — coach and mentor me. The more I got familiar with it, the more I realized that, at the end of the day, it’s just like any other job.”

Duran — who recently interned at Bain & Company — said that while the experience was unquestionably demanding, he was “surprised” by how accommodating the workplace environment had been. Rather than a “cutthroat corporate” affair, Duran described his internship as a “learning experience,” one which empowered him to make mistakes and accumulate critical tools for a future not only in the consulting industry, but also in other paths that could potentially follow. This divergence between perception and experience, Duran said, made him believe that “not getting caught up in a lot of what people were saying at Harvard and all the popular narratives” was a necessary step forward, particularly for those who were committed to the industry.

Though the efforts prominent consulting companies were making to increase diversity amongst analysts and leadership were commendable, Duran explained that they ran the risk of introducing a new problem in an attempt to solve an older one: “You have people from first-generation, underrepresented groups who have never even heard about or have not even heard other peers talking about recruiting.”

Having to be “in the know” early on in one’s Harvard career in order to secure these opportunities — despite an open interest in diverse applicants — cultivated a new pattern of elitism and exclusivity amongst minority groups. “You’re selecting from very privileged people from these groups — they are underrepresented and it’s important to have these people at the firms, but they are still coming from elite boarding schools and things of that sort. It is hard because there’s always a hand-off, because they want to combat it by creating these earlier programs, but counterintuitively, they can also select for a very specific, underrepresented person from a very privileged background.”

For Duran, the inspiration behind founding LiFT stemmed from his personal navigation of the on-campus recruitment process. “It was in the fall, and I just had absolutely no idea how to navigate this process and had no one to look over my resumé or cover letter. They said that they were optional — after the fact, I realized that they were definitely not optional. I also didn’t realize that people were talking to people at the firm, getting their name heard, prepping with people, and I just kind of went into it blind, dropped my resumé, and unsurprisingly didn’t get any interviews.”

Entering the competitive pool with little understanding of how to prepare, let alone how best to prepare, was a “very big wake up call” for Duran. “Coming into Harvard — especially as a first-generation, low-income student — you think that getting in is the hardest part. You’ll eventually get a job, but no. Now there’s another level, a next step of job opportunities that you have to jump through hoops to get into.” Duran also observed that there were not many undergraduates in the Latinx community who were in consulting, which made it even more difficult for him to seek the assistance necessary to succeed. “I just felt really frustrated, because I felt that there was no one.”

In his sophomore fall, Duran officially established LiFT. Initially composed of a handful of students, Duran shared that the organization now boasts approximately 200 members, 15 corporate sponsorships, and recognition as the 2020 Student Organization of the Year by the Harvard Dean of Students Office. Its three main components — formal mentorship programs, workshops and educational programming, and direct exposure — work together to holistically prepare prospective analysts with not only the skills but also the networks necessary to be a competitive applicant.

At an institution like Harvard, where it can seem as though everybody is prepared for just about everything, Duran told the HPR that creating a space on campus where students can “be vulnerable about these topics” was one of the most rewarding aspects of his leadership in LiFT. For an industry as particular as consulting — where the case interview can be foreign and daunting even for the most well-prepared, privileged high-school graduate — shouldering the burden alone is both emotionally exhausting and practically improbable. “You need to practice interviews with other people, network, and explicitly ask for help,” Duran explained. “Embracing that vulnerability of what you need to do, what the expectations are, and even things as little as how you should be acting in the interview, can be super helpful.”

Building LiFT’s programming and assisting fellow undergraduates is not only a fulfilling leadership experience for Duran, but also a personal opportunity to continue strengthening his own readiness for the industry and give back to the community. “I feel like I was able to give back to Harvard and future generations of Harvard students,” Duran said. “Honestly, the results have shown. Now, the amount of students I know who are Latinx who are really involved in these student organizations is definitely much more representative, and you see a lot more people getting in,” he said.

The previous fall, Duran was matched with a freshman through LiFT’s internal mentorship program. “He had no idea what consulting was, and I messaged him saying, ‘McKinsey launched a freshmen diversity internship program, you should check it out and apply, you’re a smart guy.’ I edited his resumé, we practiced interviewing, I helped him along every step of the way, and he ended up getting the offer,” Duran told the HPR. “For me, a freshman in the Latinx community getting an internship at a firm like McKinsey was unheard of. When I was at Harvard at that age, there was no one who could help me, and now it feels really nice to see my peers succeeding.”

COVID-19, Consulting, and the Uncertainty Variable

With a new, ever-changing normal introduced by the coronavirus, the uncertainty factor has reasserted itself powerfully amongst undergraduates. In a far-from-optimal reality where employers have been forced to let go of workers and an overwhelming number of businesses have had to close shop, the consulting industry appears as an increasingly stable — and consequently reassuring — option. Despite its infamous rigor, the path to becoming a partner is relatively straightforward, with generous benefits and the promise of societal status in tow. In comparison with the murky employment prospects of other fields, consulting becomes alluring in its simple promise.

Far earlier than the pandemic, however, consulting routinely seduced undergraduates through its unique capacity to conquer uncertainty with convenience. While seniors committed to the non-profit industry frequently brave a deluge of interviews alarmingly close to their graduation date, a vast majority of their consultant peers have already secured a job as early as the summer before their final undergraduate year. This frustration is aptly echoed in a Harvard Confessions post detailing how the public sector “needs to get their act together.”

“How am I barely hearing back for interviews from jobs that I applied to in January???” an anonymous undergraduate wrote. “Meanwhile, finance bro Ben has had a job secured since October. Imagine if recruiting happened in the fall along with private sector jobs, maybe 25% of Harvard students wouldn’t go into consulting out of fear for job insecurity.” Even beyond the nonprofit sector, numerous industries require undergraduates to wait considerably longer than their more corporate-oriented counterparts. Juniors who are interested in entering the architecture sector, for instance, customarily stand by until March or April to come across job postings.

Anthony Arcieri, director of Undergraduate Career Advising and Programming at Harvard College’s Office of Career Services, said the timeline of securing employment is largely dependent on the industry. “That’s another reason why some students find their way towards a more well-worn path, towards organizations and industries that hire earlier,” he explained to the HPR. “It’s comforting to know in September or October that you’ve got your summer plans lined up.”

With many undergraduates aiming to secure summer resume-builders well before their senior year, consulting has further capitalized on the attractiveness of its security by expanding its internship offerings, particularly for underclassmen. Deb Carroll, associate director of Employer Relations and Operations at Harvard College’s Office of Career Services, has witnessed this trend during the nearly 20-year period she has worked for the University. “It used to be that you didn’t have a taste of consulting until your senior year,” she told the HPR. “Like finance and tech, consulting firms are increasingly focusing on their internship programs, so we see more underclassmen hearing more about this sector, learning more about the sector, and having opportunities to apply earlier in their college experience.”

With prospective consultants securing jobs months before other students, the drastically early employment timeline can also explain an impetus among uncommitted undergraduates to fall in line with their analyst peers. “Most industries don’t hire that way, the vast majority don’t,” Arcieri said. “That’s another reason why there’s an imbalance there and why it seems like more students are going to consulting, because there’s so much more activity and noise in the early part of the year.”

Beyond the Binary

When Albert Mao ’21 first stepped foot in Cambridge as a first-year, he dreamed of becoming a doctor. The son of parents who had worked in the medical industry throughout his upbringing, Mao regarded the laboratory as the signature scene of his childhood and assumed it would become the backdrop of his own career. Graduating from a large public high school, Mao and a majority of his peers had developed skills in more traditional subjects such as science, mathematics, and literature as opposed to business and economics. “That’s kind of all I knew,” he said in hindsight.

Now a recent graduate entering a large management consulting firm in the fall, Mao is confident that his earlier aspirations did not align with his genuine interests. “I realized I did not like research,” he told the HPR. “I shadowed at a hospital, and I realized I wouldn’t like being a doctor.” Re-entering campus his sophomore year, Mao began committing to extracurriculars with a consulting bent, promptly recognizing that the skills these activities required fit snugly with his personal strengths and vision of maximum impact.

“[Consulting] suited my personality much more in the sense that it’s more fast-paced, interpersonal, problem-solving oriented, and challenging for me,” Mao said. “I thought I was making more of an impact than what I was doing in my freshman year, which was sitting in Lamont all day long memorizing chemistry equations and trying to maintain a high GPA to get into medical school.”

Mao’s first client in his consulting extracurricular was a pharmaceutical company. Throughout the course of several months, he had the opportunity to interface with top executives who revealed both their business strategies and projected benefits. “We had a huge impact on patients that quite frankly, I never would have been able to accomplish shadowing in the hospital or studying chemistry equations,” he said. Despite conventional understandings of consulting as overwhelmingly corporate, Mao’s firsthand experience was significantly more patient-oriented.

Another popular undergraduate characterization of consulting is its overwhelming monotony. Rather than enabling analysts to regularly pursue personal growth, it is believed that the high-paying occupation demands countless hours of repetitive conversations with clients, nearly identical strategizing sessions, and ultimately unfulfilling rewards. After nearly four years of collaborating with various firms, however, Mao believes that successful consulting is far more nuanced than what strangers to the industry may assume.

“There’s a consulting skill set, which is essentially being able to bounce ideas back and forth,” he told the HPR. “But there is also very niche expertise needed that is developed over decades.” Throughout his summers, Mao has come into close contact with senior partners who possess an overwhelming degree of expertise in sectors such as supply chain and digital transformation. “They’ve built up years of experience by doing hundreds of projects in that area,” he said. “It’s about combining knowledge with interpersonal skills to be able to solve a problem and also live with the solution in a way that drives impact.”

Contrary to what a considerable number of undergraduates may assume, Carroll agrees with Mao that consulting demands more than glib speaking. In fact, the hiring process itself is much more selective than some undergraduates may believe. “Landing these consulting jobs is not easy,” Carroll said. “The narrative that everybody does this implies that these consulting jobs are handed out to students who want them, but the interview and application process is pretty specific and pretty tough.” A majority of firms, for instance, will use the case interview at some point along the application process to whittle down the list of prospective analysts, an undertaking that demands considerable research preparation and communicative ingenuity. Carroll has heard from colleagues that Harvard Business School students preparing for their consulting case interviews can prepare for upwards of 100 hours.

Arcieri adds that it is critical to recognize the term “consulting” is an inherently far-reaching one, an occupation that is present in just about every sector imaginable. Throughout the duration of his time at the Office of Career Services, Arcieri has assisted countless undergraduates who enter lesser-known spheres of consulting which stray from the popular, often oversimplistic perceptions of the field at large. “I have students I advise who go into environmental consulting,” he said, a more niche speciality that is “very data-driven” and “more aligned” with the scientific disciplines Harvard offers to its students. “They’re working on issues related to regulations, stormwater runoff, and airports.”

William Leiter ’10, an independent consultant, discovered his more tailored profession after hiring freelancers to assist with marketing efforts while working at technology firms. Currently focused on growth and marketing for startups, Leiter said he appreciates both the degree to which he can become personally involved with a given startup’s development and the flexibility he has as an independent consultant.

“Startups are always short of people, so I like to make an impact in that way,” Leiter told the HPR. “It’s very tangible for me. I find it fun to be able to run tests, see what happens, and learn from them.” With much of his work being project-oriented, Leiter will undertake partnerships with clients which last between three months to well over a year. Unlike management consultants, Leiter takes a more “hands-on” approach to his commissions, not only providing recommendations but also proceeding to “[do] the thing,” such as constructing and running tests on a digital program.

“It’s a company of one, so that’s nice. That’s the appeal of doing freelance work,” Leiter added. “More and more people are freelancing, and you get a lot more flexibility doing that. Some people can get bored easily — they get tired of things and want to do something new every few months, so consulting can be good for that too since you’re going from project to project.”

Though some undergraduate courses may be more helpful than others in preparing students for his line of consulting, Leiter said a majority of skills he learned were amassed in real time. “I’m not aware of any class that would have prepared me to do the kind of work that I’m currently doing,” Leiter said. “Generally, you don’t learn it in school, you learn it on the job.” In contrast to management consulting, where graduates will immediately enter the industry as analysts, Leiter said that his expertise in technological growth and management matured through the steady accumulation of varied ventures and copious client interactions.

Other firms defy the corporate mold altogether by focusing entirely on the nonprofit sector. The Bridgespan Group, for instance, is a nonprofit organization which uses its aptitude for consulting to maximize social advancement. One subsection of their website, titled “Stories of Impact,” showcases a diverse array of nonprofits and philanthropic funds Bridespan has assisted over the years, including EdFuel, Harlem Children’s Zone, and the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation. According to Robin Mount, director of Career, Research, and International Opportunities at Harvard’s Office of Career Services, healthcare consulting is another field which has become an increasingly attractive option for Harvard’s prospective medical students.

Ithaka S+R, a nonprofit research and strategic advisory service with a mission of increasing access to knowledge and educational attainment, exemplifies an organization which challenges students’ traditional understandings of consulting services. Martin Kurzweil ’02, the director of Ithaka S+R’s Educational Transformation Program, focuses on various methods of improving postsecondary student success.

“The strategic part, which is closer to consulting, really runs the gamut,” Kurzweil said to the HPR. “We sometimes do research or program evaluation that is intended for internal purposes as opposed to publishing. We provide technical assistance on implementing different kinds of interventions or designing policies.”

Kurzweil argued that a fundamental distinction between Ithaka S+R and more traditional management consultant companies is the mission-aligned belief system encoded into his firm’s decision-making processes. “Fundamentally, consulting is about helping organizations solve problems,” Kurzweil explained to the HPR. “The way I pursue that is by making sure the problems are related to the mission that my organization and I have. We definitely have a perspective that we bring to the table. Obviously, we adapt to the particular circumstances of any given organization that we work with, but especially in choosing the work that we do and how we approach the advice that we give, we always bear that in mind.”

The American Talent Initiative — an undertaking involving Ithaka S+R and the Aspen Institute’s College Excellent Program designed to increase collegiate opportunities for low-income students — is one such example. “We’ve signed up 133 institutions whose presidents have endorsed our national goal, and we’re working with those institutions to set their individual goals aligned with the national goal,” Kurzweil said. Principal responsibilities of leadership include convening clients to further develop best practices and strategy, conducting research, and monitoring the progress of universities.

The mission-oriented approach of Ithaka S+R frequently fails to surface in its more mainstream management consulting counterparts. As explained by a business column published by The Economist titled “McKinsey’s partners suffer from collective self-delusion,” the top-tier firm habitually cold-shoulders accepted notions of moral do’s and don’ts. The editorial argues that McKinsey consultants “have a mantra that puts their clients’ interests above their own” as well as “a belief, drawn from the firm’s pristine heritage, that no one knows better how to distinguish between right and wrong.” As evidenced in several alarming scandals, one of which exposed the firm for considerable involvement in the exacerbation of America’s opioid epidemic, such a high claim strongly contradicts the status quo. Instead, it has been the case time and again that the firm’s “moral compass [goes] haywire,” a phenomenon the column attributes to the “lure of lucre.”

The career trajectory and legacy of Alysha Johnson Williams ’14 — the director of Pathways to Practice at Harvard’s Center for Public Service & Engaged Scholarship — closely aligns with that of Ithaka S+R and challenges the dominant narrative of larger consulting firms such as McKinsey. After graduating from Harvard College in 2014, Williams began work at a firm which provided consulting services to various school districts regarding K-12 education. Despite the “bad connotation” undergraduates routinely ascribe to consulting on campus, Williams told the HPR she was “really excited about tackling problems in education.”

Rather than be introduced to an employment opportunity with ambiguous logistical and moral obligations, Johnson said her first post-graduation commitment was straightforward in its various expectations and offerings. “When I received the offer, I was very cognizant about what I was going to that firm to do,” Johnson said. “I wanted to get a 30,000 foot view of education policy and practices, and that’s exactly what I was able to do.”

One question Williams encourages undergraduates to pose to themselves is the caliber of insights from lived experience they can provide to clients, particularly graduates who are entering firms fresh out of college. “That’s another difficult place consulting can put students in,” Williams said. “They’re in these really great positions to support people, but if they’re not coming with experience or on-the-ground knowledge, it can be a little presumptuous to come in and think you’re going to change things.” Though Williams said it was certainly possible for fledgling analysts to possess relevant insight, she stressed the necessity of remaining “cognizant” of this dynamic when considering “consulting as a profession.”

Despite what may be interpreted as skepticism, Williams said she never faults undergraduates for pursuing a career in the industry. The more fundamental issue, however, arises when students are conditioned to identify consulting as the singular, most viable post-graduation pathway. Williams described the consequence of this understanding to be undergraduates making the faulty assumption that “[using] their Harvard degree” is synonymous with boasting a staggering salary. “If your circumstances dictate that you’re going to need a certain level of income post-graduation, consulting may be able to do that for you,” she reasoned. “However, finances are just one piece of the puzzle. I wish more people would weigh all of the pieces of the puzzle before making that decision to go into it, especially if folks are just following that path for the money or for the ‘prestige.’”

It remains the responsibility of the University, Williams argued, to ensure students leave campus with not only a comprehensive understanding of consulting, but also the conviction that there exist manifold other career opportunities. “Consulting as a profession is something that’s interesting and unique, and it shouldn’t be discounted just because it has a negative connotation on campus, but it doesn’t have to be everything… the end-all-be-all, this marker of success,” Williams said. “I think that’s where the frustration lies — consulting is perceived as being this prestigious thing, and we can work to make sure that we’re presenting different options and different ways for folks to explore.”

The Confused Ambition of a Harvard Imagination

If there is any one thing in abundance on Harvard’s premises, it is ambition. It is omnipresent in the eyes of every burgeoning scholar, ceaselessly manifesting itself in the most ordinary and exceptional circumstances. It is very likely that a greater part of each year’s incoming freshman class genuinely fantasizes about transforming the world, as earnestly conveyed in the written application and interview process. It seems exceedingly clear that outgoing seniors, wisened versions of their first-year selves, will wave goodbye to Cambridge with that same — if not dramatically strengthened — desire to do good.

However, if consulting is considered a morally reprehensible field, the portrait above loses its glossy sheen. For many firms, consulting can be interpreted as assisting clientele who already possess a disproportionate degree of prestige, wealth, and societal influence. Though this framework of classifying the industry may be understandably judged as a reductive one, it is roughly applicable to numerous companies, especially those which listen to the siren song of money first and the quieter hum of moral decency second.

Each Harvard student must learn to wrestle with a unique amalgamation of ambition and conscience, of exterior anxieties and interior dreams. The throughline of these undergraduate experiences is the all too familiar desire to succeed — whatever interpretation somebody may have of the word. Too often, to no fault of the student alone, this desire to do well overpowers one’s original conviction to do good. Rather than embracing the broader, messier logic of transformative learning, undergraduates are compelled to collapse into the cleanliness of professionalism and operate under the straightforward — albeit brutal — logic of always having to finish on top.

Saffron Huang ’20 similarly argues that the fruits of a Harvard education yield a proficiency in management rather than an inclination to transform. Published in Palladium — a magazine focused on prospective governance and societal issues — Huang’s article titled “Harvard Creates Managers Instead of Elites” describes the University’s “lack of meaningful guidance and substantive vision, the insular bubble students live in, and the nudges towards marginal optimization” as the institutional assassins of “innovative, interesting, and socially beneficial ambition.” According to Huang, rather than cultivate a purposeful elite who wield their power with heightened sensibility, Harvard generates graduates who possess an “acquisitive-striver mindset,” a frame of reasoning which results in the “detriment of American culture at large.”

“It is possible to teach people to do visionary, generative, and purpose-defining work,” Huang contends. “And as Harvard students, admitted for talent and ambition and placed in a position of elite privilege, we are the exact people one would expect to be taught this. But the Harvard social environment never teaches students what this generative part of reality looks like. This creates a managerial, not a transformative and strategic, elite.”

Guillermo S. Hava, an editorial columnist for The Harvard Crimson, calls into question the existential calling of a Veritas-stamped undergraduate degree in his article titled “McKinsey, Snakes, and the Purpose of a Harvard Education.” Referencing McKinsey’s exposed complicity in the opioid epidemic, Hava reminds his reader that the company is occasionally referred to as “McHarvard” for its recruiting triumphs on campus. While the firm’s “aggressive hiring policy” may impel departing undergraduates toward consulting, he describes the outlook that students are without agency as “both naive and shortsighted.”

“A campus filled with overachievers is bound to seek easy indicators of prestige, and money and its comfort can be tempting,” Hava wrote. “Our courses teach the importance of curiosity, persistence, and intellectual promise. The halls where they take place and the elitist clubs that dominate our social life instill a very different story. Harvard remains an icon of an economic elite, not just an academic one — no matter the college’s efforts to the contrary.”

The undergraduate’s imagination is a necessarily restless one, loosely defined by personal truth and striving. Placed underneath both the institutional framework and social mechanisms of the world’s most prestigious university, it comes as little surprise that this imagination will instinctively mutate into a leaner, more unforgiving adaptation of its prior form. Still, the age-old conundrum of how best to embody one’s truest, most noble principles is a human riddle worth attempting to solve, no matter how elusive its solution.