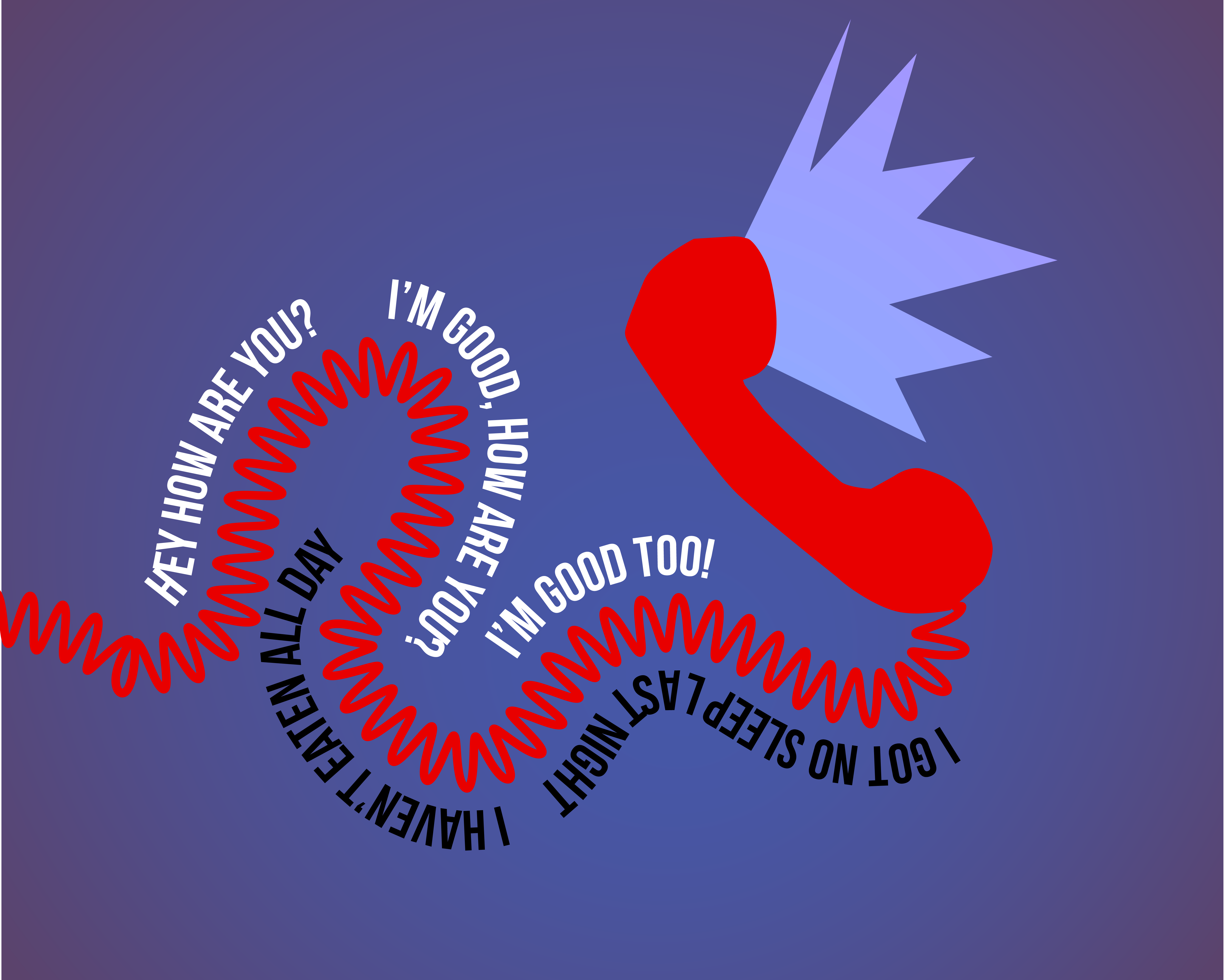

“Hey, how are you?”—a question, a ritual. The words tumble in response: “I’m good, how are you?” But you are not good, actually. And neither is the person asking you. She is feeling lonely and isolated from her friends, and you are feeling too anxious to sleep or eat.

And so there is an underground crisis, really. Students speak in hyperbole — “I want to die” or “I got no sleep last night” — so much so that the severity of campus’s worsening mental health landscape is drowned in a sea of other students adding to the chorus, making it normal, or at least not extraordinary. But it is. The overall mental health of undergraduate students at Harvard has worsened in the last five years, with the number of students self-reporting bouts of depression or anxiety increasing nine and 11%, respectively, from 2014 to 2018.

There’s more where that came from. Harvard’s “Report of the Task Force on Managing Student Mental Health,” released in July 2020, numbering nearly 50 pages and produced over the course of a year by a cohort of over 50 Harvard professors, administrators, medical professionals, and others, sought to examine the current state of mental health at Harvard, identify resources for addressing issues, and make recommendations for improvement. After conducting surveys, institutional data, and focus groups, the findings were clear:

“Our investigation confirmed that Harvard students are experiencing rising levels of depression and anxiety disorders, and high and widespread levels of anxiety, depression, loneliness, and other conditions. In addition, undergraduates reported high levels of stress, overwork, concern about measuring up to peers, and inability to maintain healthy coping strategies.”

But the problem cannot be traced to one source, only. The crisis is really twofold: institutional and cultural. These elements are not stratified, but rather inextricably linked. What I mean is this: The breadth of mental health services offered at Harvard are a tremendous resource, but only if they can be utilized. The potential for utilization comes down to the ability for CAMHS to clearly and effectively advertise how to get help, what kind of help is necessary, when, and also students’ ability to recognize when they need help. Harvard’s culture’s tendency to reward students for prioritizing external output over internal self-awareness hinders this utilization. And so here, we have the central mechanism eroding the mental health of Harvard students and amplifying a silent crisis.

Institution

Jordan Woods ’24 knew something was wrong in mid-March of his freshman spring. Given that freshmen had technically not been invited back to campus that semester due to COVID-19 that semester, he, like many at the time, was living off-campus with friends. After hearing his concerns, his proctor told him to set up an appointment with Harvard’s Counseling and Mental Health Services (CAMHS). Jordan visited the CAMHS website and took one of the depression “screening” quizzes, as he called them in an interview with the HPR, or non-diagnostic advisory evaluations of a student’s mental state and providing direction. “It said I might have depression,” Woods said.

Jarred by the result, he turned to the patient portal, which is supposed to be a one-stop-shop for all student health needs at Harvard. Here, students can schedule appointments, secure vaccines or flu shots, upload immunization records, and more. He made an appointment with CAMHS for an initial consultation over the phone. A few weeks later, a clinician called him at 9 a.m. They had a five-minute conversation, during which she gave Jordan information about counselors who were available for longer sessions.

Jordan is Black, so he knew he wanted to talk to a person of color, preferably a Black male. “They had about two of those,” Jordan laughed, referring to clinicians of color. “And there were no Black males.”

It wasn’t until finals week in May — almost eight weeks later — that Jordan had his preliminary session with a CAMHS counselor. By then, he had already moved back home to Harlem, NY, and, as the summer provided relief from a hectic year, the appointments grew inconsistent. He felt the issues he faced in March weren’t pressing or fresh enough to discuss anymore. “The ship had sailed,” he said.

“The whole experience was—” he paused. “Just really difficult.” He wished the process was more seamless, with fewer hoops and red tape, and that CAMHS could be a place he could go if he was feeling bad and just needed to talk to someone. It was a waiting game that kept him in emotional limbo for weeks, and because he didn’t feel his issue prompted emergency care, he “just had to soldier forth.”

The undergraduate students who participated in focus groups for the Task Force report would have likely agreed with Jordan. Appointments are always difficult to secure, whether it be for an initial consultation or for ongoing care. The longest waits take place during the fall semester and have generally increased since 2018. The Harvard Crimson reported in early March of this year that wait times have reached six weeks. Students in the focus group also reported that they had a hard time finding a provider who shared their identity.

And then there’s the challenge of navigating CAMHS in the first place. Jordan did have an option to seek immediate care — CAMHS launched a 24/7 mental health hotline in August 2021 that provides immediate support from licensed therapists. They’ve received 1,600 calls since their launch. But he didn’t know about it.

There are a myriad of resources available on campus: CAMHS, peer counseling groups like Eating Concerns Hotline and Outreach (ECHO), Room 13, Active Minds, and Indigo Peer Counseling. It takes time to learn the difference between what each service offers, how to access them, and which one is the right fit. Besides, not all students are comfortable going to a peer for mental health counseling. “Onus shouldn’t be on students, this shouldn’t be their job,” wrote one focus group participant.

“Above all, there seemed to be confusion about CAMHS as a resource” concludes the report. “Students were often unclear about when, where, and how to speak to a mental health professional.”

“I had no idea what the process was until the proctor told me what I needed to do,” said Jordan.

Institutionally, then, the problem is two-fold: Not only are there insufficient resources to meet the needs of students, but students themselves are also ill-equipped to identify and proactively navigate the help they need. It’s unsurprising that 76%of students said they’d prefer to deal with their emotional problems on their own.

Culture

During her freshman spring, at home for online classes, Nur Kader ‘24 began to notice that stress drastically reduced — even eliminated — her appetite. It wasn’t anything too severe, but she had never experienced it before: disordered eating. She thought about talking to a professional, so she reached out to CAMHS in February to schedule her initial consultation. The wait wasn’t too long, and she was able to receive ongoing care from an eating concerns specialist. But the specialist could only meet once a month, and, similar to Jordan, Nur was worried that the limited time wasn’t enough to get to the root of the issue. After all, an imminent emergency could come and go during the one-month gap between sessions, and outside of such periods, the underlying problem was chronic but usually repressible.

After less than 10 meetings, the specialist told Nur that she “had the tools to know what to do.” “It’s easy to say that when I’m not in crisis,” Nur said in an interview with the HPR. “If I’m in a stressful situation again, will I be okay, or will I revert back?”

It’s hard to know. Nur wasn’t able to continue sessions over the summer, so the “continuity of care,” as she puts it, was a bit lacking. But the meetings were generally helpful, and she felt hopeful going into her sophomore fall on campus.

As school life began to ramp up and the Boston chill set in, Nur began to notice the eating habits she had adopted last spring reemerge, but to a lesser degree. This time, Nur was more equipped to immediately recognize that something was wrong and that she wanted more constant care. So she talked to her parents about seeing an out-of-university specialist more frequently.

Receiving professional care, though, was only a small part of what Nur called a “total lifestyle switch,” which consisted of regulating her stress levels on a daily basis and practicing preventative rather than reactionary self-care.

“I don’t think we always have to take the harder way,” said Nur. “Some people think ‘the grind’ is paramount to everything else. I don’t think stress has to be our primary motivator.”

Nur is onto something interesting here. The phrase “grind” is used ubiquitously on campus to refer simply to doing work and living life. Even if it is not implied, though, the word has become synonymous with the unhappiness and intensity with which students go about doing things. Work is then linked to stress, and students believe that to be truly working, one must be “grinding”: If life’s not packed to the brim, you’re not doing or working enough. Even more problematically, to be on the grind, at the expense of your mental health, is almost a badge of honor. It’s a cultural indicator that you, too, are a part of this larger effort to “get things done.” People are not in a rush to tell others about their empty afternoons and the time they take for themselves. It may come off like they’re a slacker, or just not serious about school. Fear of being perceived as unproductive, thus, only serves to glorify the glorification of the unceasing “grind” life.

Somehow, though, Nur has managed to develop personal work habits that best serve her mental health. She realized she doesn’t get things done when she’s stressed. She doesn’t like saving all of her fun for the weekend.

Despite being “in a demanding field like physics,” Nur isn’t always “on the grind.” “Sometimes I think ‘Am I not as serious as a student?’,” she said. “No, I just work differently than other people might.” Amid pervasive “p-set (problem-set) culture,” the cultural phenomenon present in STEM fields that emphasizes extensive amounts of work and rigor, and the growing prevalence of the “grind,” Nur has established a work-life style that prioritizes what many like to call “self-care.”

Personal

The notion of self-care originated in the 1960s as a medical concept coined by those working in professions focused on patient-psychology, like trauma therapy or social work. But it wasn’t until the civil and women’s rights movements that self-care grew into an act of political defiance, particularly against White, patriarchal systems. Health, thus, became inextricably linked to preserving the well-being of the holistic self in the face of a high-pressure society, not just the absence of illness.

Since then, we can all agree that the idea of wellness has become commodified through the marketing of beauty products, clothing lines, dieting, and much more. Being “well” has become synonymous with an image of being White and thin. Regardless of what it has become, however, self-care was originally about what Nur has established for herself: a method of preventative preservation. In its nature, Nur’s process is not reactionary.

Harvard students are dominated by a certain cognitive dissonance. We know we must take care of ourselves to live. More often than not, however, this understanding is overpowered by a tendency to prioritize external output and often unreasonable levels of productivity. Instead, undergraduates are encouraged by others to rest, to take “self-care days,” and to prioritize their mental health. But sidelining work, even temporarily, to pursue wellness can ultimately manifest as procrastination and just causes assignments to pile up. At its worst, severe procrastination, while perceived as a mechanism of self-care, may only regress a student’s mental health issues and cause them to spiral.

Our outsides do not match our insides. That is, we do not know how to close the gap between our intentions and our behaviors, to do things that are aligned with what we know is good for us. We over-extend. We are too hard on ourselves. We skip meals. We do not sleep. Why? What are we chasing?

To truly fill the gap and find a solution, we cannot merely react to these mistakes once they’re made. For students to feel cared for when they do reach out, CAMHS needs to prepare ahead of time, staffing more clinicians and better-streamlining resource accessibility before waitlists become unmanageable. But beyond this, there is a responsibility we have to ourselves. We have to take the step to seek preventative rather than reactionary care. It is not enough to destigmatize mental health; we must also create a campus where seeking resources is not an act that requires a significant mental leap of recognition or is perceived as a gesture of defeat.

By doing so, we can develop the self-awareness necessary to understand when we are doing well, and when we are not. Seeing a professional helps us better know ourselves, which can in turn create a positive feedback loop that arms us the next time a crisis hits. Mental health is, then, holistic. It’s not just about talking to a counselor once a week or taking a pill. It’s about practicing consistent conscious dedication to taking care of oneself.

If the above measures are taken, a student may be able to make their life a little bit better, or more manageable. Only 34% of students at Harvard said they’d be comfortable seeking professional help if “confronted with an emotional problem.” This figure needs to be higher. Students are not to blame. No one is, really. Struggles with mental and emotional health are a result of cultural and institutional pressures, brain chemistry, home life, interpersonal relationships, and so much more Roadblocks will always exist. What matters is that we develop personal tools to ensure our well-being, and continue to reevaluate how our living influences our mental health. The work is hard. But getting there is so worth it.