In my first encounter with a United Nations agency in Viet Nam, I met two officers. One was a tall white woman with frizzy blonde hair, a crisp blue suit and tortoise glasses and the other was a Vietnamese woman, shorter in stature, with kind eyes and a stoic demeanor. Without much thought, I assumed that the White officer held a superior position. It wasn’t until I spoke to the Vietnamese officer in our native tongue that I realized I was wrong: It was she who had the final say.

UN country offices in Viet Nam, I later observed, have staff that are at least 80-90% local, serving positions ranging from P-2 (most junior officer) to D-2 (highest director level). The international staff hailed from a plethora of countries and regions, mostly Western, but other Global South countries as well. My agency’s Deputy Resident Representative, (second-in-command) at the time, was Afghan. The Vietnamese staff, too, hailed from diverse backgrounds, from previous youth activists to career diplomats and hardcore government officials. Though it was by no means a perfect working environment, the UN country office provided a nurturing space where I could advance youth voices in climate policy — my area of passion — while learning about the nuances of development work. Never have I been surrounded by more hardworking, earnest and inspirational colleagues.

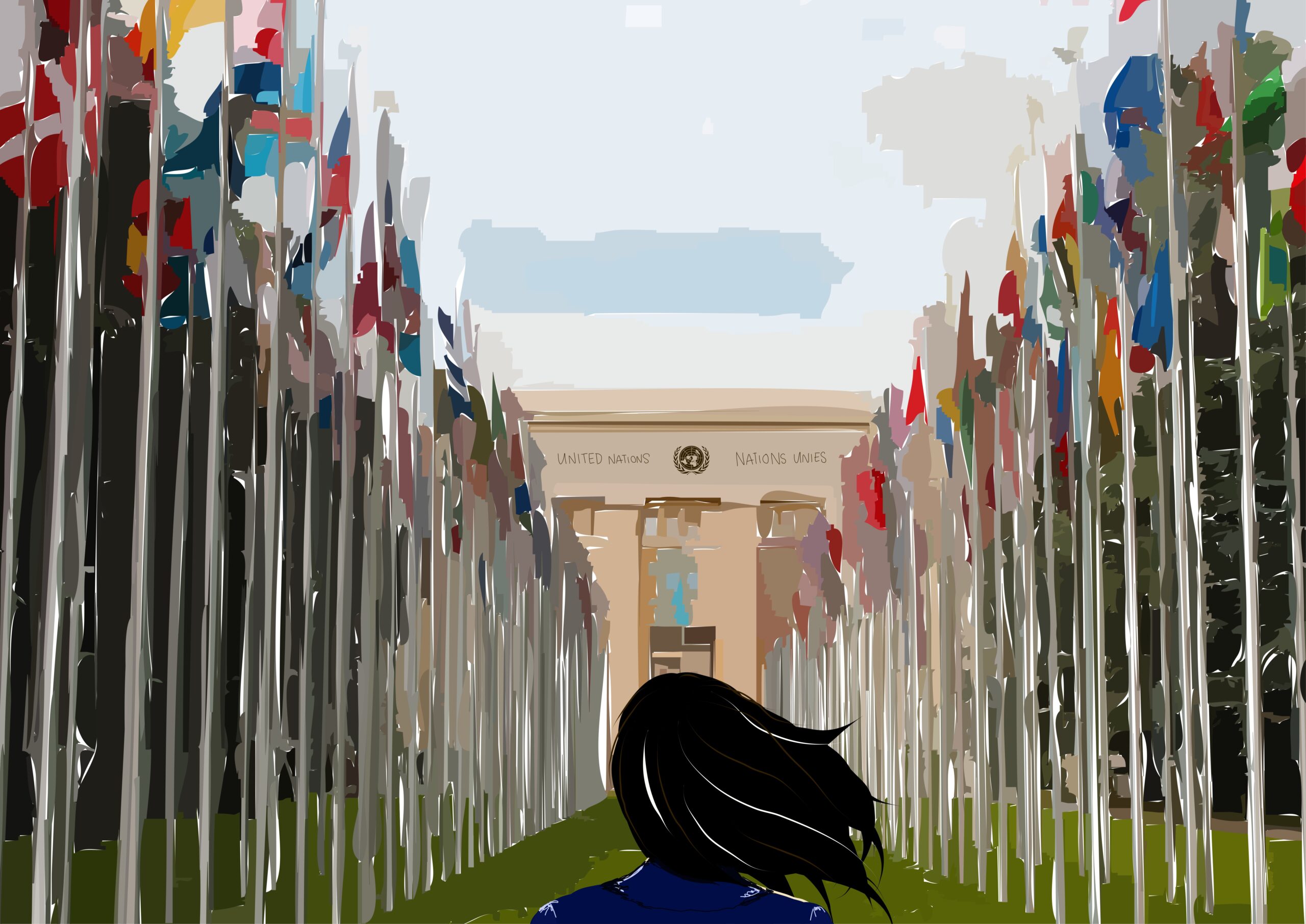

I quickly realized that two assumptions I had previously made about the UN were wrong: that it was a white-dominated institution and that its work consisted mainly of diplomats pointlessly arguing in an ivory tower.

The UN is a gargantuan and nebulous operation; most of those working within it still struggle to map out all the different councils, agencies and their overlapping mandates. If you’re a student in the U.S., chances are that your only encounter with this system has been through “Model UN” conferences, which produce more investment banking executives than future UN officials. What is broadcasted is drama and powerplay — the U.S.’s smug dominance, Russia’s theatrics, the vetoed resolutions and failed interventions.

What’s too often overlooked, or simply dismissed as an operation of “Western hegemony,” is the grueling on-the-ground work that happens within each agency, province, and operation. From installing flood-resilient houses or adding one line of text in a local law to ensure inclusivity, UN officials, oftentimes hailing from the same country or region as those they assist, resist the constraints of politics to implement real change at the national level. They can even act as liaison between civil society and close-minded, repressive regimes.

I am compelled to state, as every defender of the UN system is inevitably compelled, that I am not asserting the system is without fault. I am not blind to the alleged sexual assault within Peacekeeping troops, or the inefficiencies, politicking and window-dressing I myself witnessed within the country office. Nevertheless, I believe that too many diatribes against the UN are made from the perspective of armchair intellectuals, the American intelligentsia that jabs at the broad “ideology” or reputation of development work rather than engaging in rigorous, case-by-case analyses of its successes and failures.

In a perfect world, we wouldn’t need development agencies; we wouldn’t have colonialism, or slavery, or the systematic subjugation of entire peoples and regions by the old colonial empires. Stable institutions would evolve on their own with equal power, and the Human Development Index (HDI) would be equally green across the globe. But I’m not interested in arguing philosophy or theory; I’m writing about facts. And the facts remain that, due to a combination of historical and environmental factors, a large portion of the global population resides in areas that struggle to accumulate wealth over time without significant external investment.

Growing up in Viet Nam, the impact and importance of foreign aid was not something my peers or I could afford to ignore. Development work, therefore, is not a question of if, but how.

As a well-meaning U.S. citizen, or citizen of any donor country, you have tremendous power and responsibility to reject the current state of international development, while still actively engaging in development work. Dismissing the entire UN system as incurably biased or ineffective demeans the power of its 142 non-founding member states, nearly 75% of the organization’s membership, which hail from the “Global South”. It is they who demanded for a focus on the development agenda and North-South technological transfer we take for granted now, who played a central role in the creation of the UN Development Programme, HDI and Sustainable Development Goals, and who constantly redefine the answer to “How are you?” on an international scale.

The UN has changed in fundamental ways since its founding, and I believe that despite the bureaucracy and resistance of donor countries, it has the potential to become a better institution. I may be naive; after all, my experience was confined to six months with a truly exceptional and inspirational team in one country office. There are veteran officials much more disenchanted than myself.

But after all, what are institutions but the individuals they are comprised of? External criticism is important, but internal change—from the consultant who speaks the truth or the officer who advocates for those on the ground — is even more critical. Demographic change within UN staff, with greater diversity and representation from the Global South in leadership positions, is also happening. That gives me tremendous hope — a hope that the next young, bright-eyed UN staffer will have an acute awareness of the diversity of those they work alongside.

Ultimately, if you want to form your own judgment on the UN, or more broadly, development work as a whole, I encourage you to do research — look at the reports in local newspapers, scan the Guardian’s 70th-anniversary assessment, and read “Poor Economics,” a seminal evaluation of development which employs empirical data from randomized control trials. If you truly care, become a UN volunteer or consultant, engage with those who work on the ground. Perhaps then you will see this organization and its work for their concrete results: The small wins that, over time, accumulate to something more than a newspaper headline. If you’re lucky, you will see how your contribution changes others’ lives for the better. It will certainly change yours.