As part of its effort to address the looming threat of climate change, the Biden administration has set the widespread adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) as one of the nation’s top environmental priorities. In 2021, President Biden signed an ambitious executive order setting a target for half of all new vehicle sales in 2030 to be electric. Since then, the administration has implemented new tax credits, incentives for electrifying school bus fleets and investments to upgrade the USPS fleet with electric vehicles under the Inflation Reduction Act, strategies aimed at increasing the financial and logistical accessibility of EVs across the board.

Despite these record investments, American consumers still aren’t biting.

Although sales are growing year-over-year, the rate of growth in the EV market has been slower than many automakers originally anticipated. In 2023, EV sales constituted only 7.6% of total U.S. vehicle sales. In comparison, gasoline vehicles accounted for nearly three-quarters of total sales. Even once-disruptive EV companies such as Tesla are facing hard times, with the company’s sales dropping for a second quarter in a row and recovering to meet baseline expectations in the third quarter.

According to a 2023 BBC report, the cause behind the disappointing adoption of vehicles can be boiled down to three reasons: high costs, a lack of charging infrastructure, and a narrow range of models — all of which can be attributed to sluggish action from U.S. automakers and government officials.

For example, the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocated a record $7.5 billion to build a national network of open EV charging stations. Although analysts estimate that this funding is enough to construct 5,000 stations, only seven stations have been opened for public use mainly due to a scarcity of chargers that meet the administration’s quality standards. The Biden administration continues to assert that it anticipates achieving its target of 500,000 charging stations by 2026.

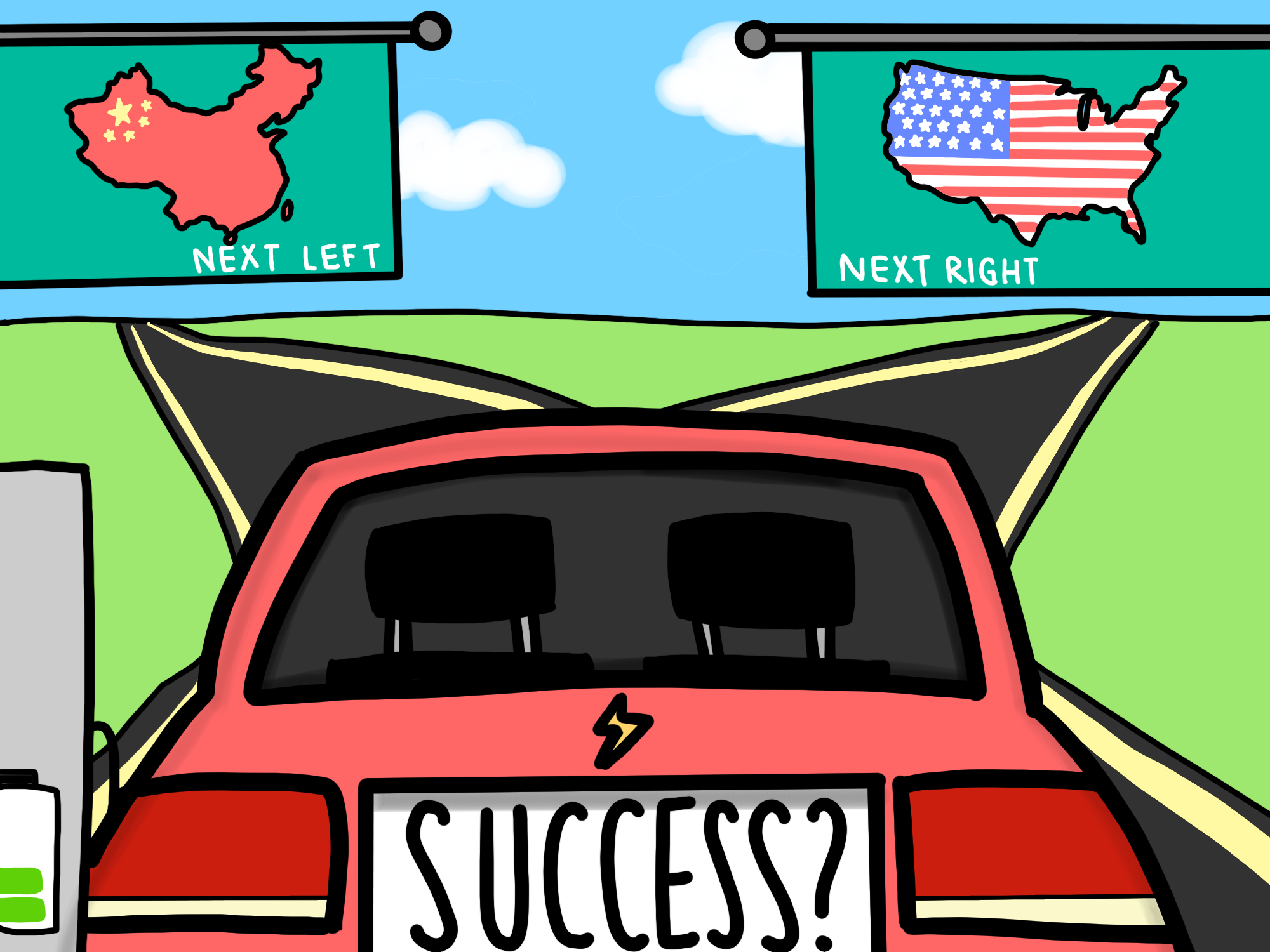

With news of slowing growth rolling in, government officials and environmentalists have become anxious that the policies currently in place are insufficient to meet the Biden administration’s original goals. These concerns are amplified by the rapid market domination of a superpower competitor: China.

As countries across the globe, particularly in the West, seek to reach their own EV adoption goals, China has stood out as an exporter of cheap cars at high volumes. In China, domestic EV sales increased by 82% in 2022, constituting more than 60% of global EV sales. Despite arriving on the global EV scene later than early EV adopters such as the U.S. and Scandinavian nations, China made up 35% of global EV exports in 2022. The preeminent Chinese EV automaker, Build Your Dreams (BYD), sold more EVs than Tesla in Q4 2023.

Yet, as Chinese EVs dominate overseas markets, they have been notably absent from American roads — which is no coincidence. Although cheap Chinese-made EVs may help the U.S. reach its sales goals, they pose a major risk to American national security and domestic production. Government officials, including U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, have warned that Chinese EVs could potentially transmit location data, microphone and camera recordings, and personal driver information to the Chinese government. In response to these threats, the Biden administration has increased tariffs on Chinese EVs from 25% to 100%, effectively cutting off Chinese automakers’ access to the American electric vehicle market.

However, history shows that blocking foreign sales does not automatically cause domestic markets to flourish. In 2012, a comparable Obama-era tariff on Chinese-made solar panels succeeded in restricting direct imports but failed to promote a domestic solar panel industry. Currently, the U.S. remains heavily dependent on solar panel imports from companies based in Southeast Asia, especially in Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, many of which have connections to China.

Thus, the only policies that can effectively drive sales of American-made vehicles are strong standards that drive innovation and the deployment of cleaner vehicles. Aside from the need to build much-needed infrastructure and increase EV tax subsidies, there are several creative policies that the U.S. could implement by looking at how China rapidly grew its EV market.

One unique initiative in China was a partnership between EV automakers and taxi companies to replace taxi fleets with EVs in cities. With such a large sample size of vehicles, EV companies could test and improve upon different charging schedules and charging station maps that would optimize the performance of the vehicles’ core battery technology.

EV companies also experimented with electric battery technology in adjacent target markets that would easily transfer to electric vehicles. One of the most useful targets was the electric bus industry, which requires more powerful and long-lasting batteries to carry the weight of a heavier frame and more passengers. These new batteries were not only on the frontier of battery technology, but also guaranteed to work for less-intensive vehicles.

If the U.S. government encourages companies to follow these strategies through policy or financial incentives, the resulting advancements in EV battery technology and normalization of EVs could create a diverse range of high-quality vehicles that rival gasoline vehicles, and lead the U.S. to reach its own EV adoption milestones.

However, it is important to note that the U.S. and Chinese governments operate in distinct economies. In China, the state heavily funds subsidies, controls state-owned enterprises, and mandates that private firms establish Communist Party committees. The government directs corporate goals through strict mandates. In contrast, the U.S. influences the private sector primarily through regulations and incentives, allowing market forces to guide corporate actions — giving U.S. national policies less authority over corporate action.

Despite these challenges, the hallmark free-market economy of the U.S. facilitated the rise of automotive giants, such as General Motors and Ford, which have left an indelible mark on the industry. With the right incentives, the same drive for innovation that led these companies to pioneer processes for the mass production of cars can be redirected toward the development of affordable and efficient EVs with the right incentives.

With 2030 coming up in six short years, it is either now or never that the U.S. gears up to reach the EV milestones it optimistically announced at the start of the decade. If the U.S. wishes to reach its sustainability goals and reap the environmental and economic benefits it seeks, then it needs to be willing to take the leap of faith to complete the full transition. By tying protectionist policies to strong standards that drive innovation and deployment of cleaner vehicles, the U.S. can jumpstart the type of growth that its automaking industry has been historically known for.