On the very last day of the Constitutional Convention, George Washington solemnly stepped forward to the stage in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. After back-and-forth debates about the size of the House of Representatives, the president of the convention himself took charge. In his history-changing speech, Washington openly supported Nathaniel Gorham’s motion to give Congress the power to expand the House of Representatives in accordance with population growth, ensuring a ratio of one representative for every 30,000 constituents. Washington’s speech convinced the rest of the founding fathers that increasing the size of the House would strengthen the “security of the rights and the interests of the people.” Gorham’s motion passed unanimously.

In line with Gorham’s motion, Congress enlarged the House from 65 to 69 members in 1791, following the first U.S. census. This change created a ratio of 33,000 constituents per representative in the House, aligning with Washington’s and Gortham’s hopes. Since then, Congress has passed bills to increase the size of the House incrementally to account for population growth.

However, congressional expansion stopped on Aug. 8, 1911. The Apportionment Act of 1911 capped the number of representatives at 433, with a provision to add two more seats after Arizona and New Mexico joined the union in 1912. Much, however, has changed since 1911. The U.S. has grown by two states — Alaska, and Hawaii. Women gained voting rights, doubling the number of voting constituents. The number of congressional representatives, though, has remained unchanged.

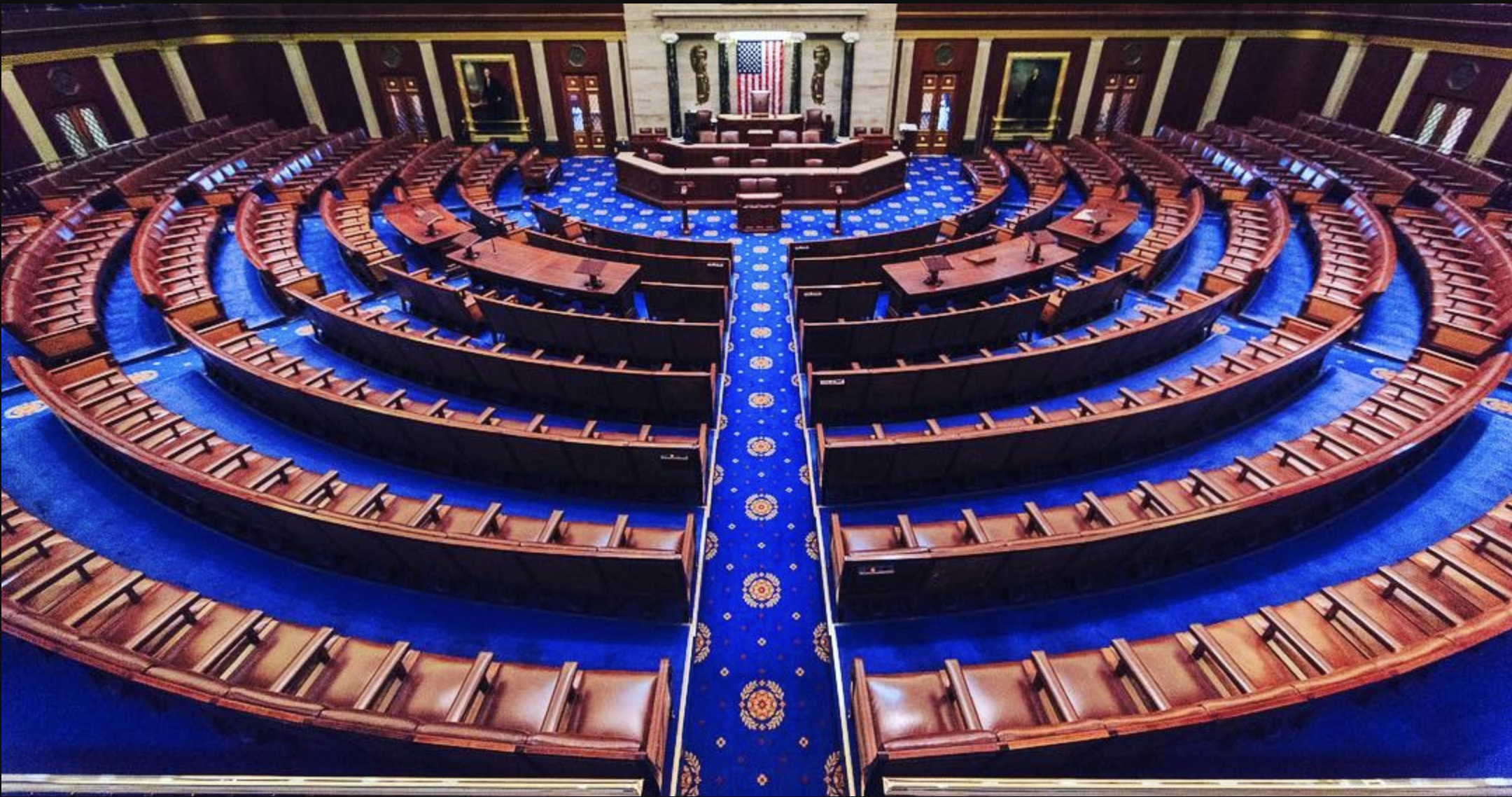

Since 1911, the U.S. population has tripled, but the number of House seats has remained stagnant at 435. Today, one House member represents around 761,000 Americans. This is far higher than the founding fathers’ expectations. It’s time for the U.S. to consider expanding Congress again.

One of the most appealing arguments for enlarging the House is that it will increase American political efficacy rates. Political efficacy refers to the sentiment that one’s political actions — such as voting and contacting congressional representatives — have real impacts on government decisions. Political scientists agree that political efficacy rates are an excellent indicator of the health of a democracy, with high political efficacy rates being associated with “more positive views of government across realms.” Any boost in political efficacy would be welcome for the longest running democracy on Earth.

Unfortunately, according to a 2022 Pew Research Center poll, only 27% of Americans say the American political system allows them to have a fair amount of influence on politics. One-third of U.S. citizens, across party lines, feel politically alienated. Furthermore, America is suffering from historically low public trust in government. In 1964, 77% of Americans believed that the U.S. government would do what was right most of the time. In just six decades, that number has dropped significantly, to a mere 22%. With an increasingly polarized political climate, it is nearly impossible for one person to represent the diverse views of 761,000 fellow Americans. Therefore, it is natural for Americans to assume that they are not being represented. In fact, it’s more than natural. It’s true.

Thankfully, more representatives in Congress is a possible solution. Research shows that in proportional representation systems, voters are likely to have stronger political preferences, which enhances political efficacy and increases voter participation. More representatives would lead to smaller districts with fewer number of voters which leads to individual voters having a bigger say in the representative’s decisions. Emailing your representatives, participating in canvassing, or phone-banking could have a much greater impact in the result of the election. Therefore, with more representatives, citizens would be better represented; lawmakers could focus more on doing right by their constituents.

More representatives would lead to greater diversity in Congress as well. Although racial and ethnic diversity in Congress continues to increase, there’s still a great deal of work to do to make Congress look like the country it serves. For example, the House has an average age of 58, much older than the American median age of 38.8. Despite this fact, 94% of incumbent House members won reelection in 2022 — due, in part, to the powerful incumbency advantage.

Newly created seats will not be burdened by this same issue of incumbency. By establishing fresh, unheld seats in the House of Representatives, room will finally be made for young, diverse politicians who will bring equally new and diverse ideas to the table.

Critics of expanding the House argue that a step toward greater direct democracy will only complicate the already convoluted Congress, exacerbating the legislative backlog. Yet, other nations with lower ratios of representatives-to-constituents clearly demonstrate that larger representative bodies can be not only as functional, but potentially even more productive than smaller ones. The British Parliament has 215 more members than the House of Representatives, even though the U.K. population is roughly one-fifth of the U.S. population. Germany has 709 Bundestag members. France’s National Assembly has 577 deputies, still higher than the United States. Yet, many of these bodies were substantially more productive than the United States Congress. The 117th Congress only passed 27 bills in 2023, compared to 57 in the UK and 201 in the second session of the Canadian parliament.

Other countries’ legislatures prove that more representatives doesn’t necessarily lead to political chaos. In fact, more representatives often leads to more productive legislatures. Global knowledge, technology, and governmental institutions have evolved significantly over the past century. It’s time for the number 435 to evolve as well.

There have been numerous attempts to reshape the House of Representatives, one of which was the very first constitutional amendment proposed to the United States Constitution. In 1789, James Madison proposed 12 amendments to the Constitution in response to Anti-Federalists’ concerns about giving too much power to the national government. Ten of them were ratified by the state legislatures, becoming the Bill of Rights. One of the two remaining amendments was ratified in 1992 as the 27th amendment. which forbids changes to the salary of Congress members from taking effect until the next election.

However, the first proposed amendment is still not ratified by the states to this day. The Congressional Apportionment Amendment lays out a mathematical formula for the number of representatives. If the Congressional Apportionment Amendment passed, we would have more than 6,000 representatives today, as opposed to the 435 with seats in 2024. However, the amendment only passed in 11 states, and it remains in the void as one of six unratified constitutional amendments — alongside the Equal Rights Amendment and the D.C. Voting Rights Amendment.

More recently, the 2023 REAL House Act, sponsored by Rep. Earl Blumenauer, D-Ore., would increase the number of voting House members to 585 after the 2030 census. Since only the 1929 Permanent Apportionment Act currently bans expanding the House, Blumenauer’s proposed legislation could nullify the law with a simple majority vote. The REAL House Act is just one of the many proposals for expanding the House. Although experts argue for different types of reform such as the Wyoming Rule, adding 139 seats, or the cube root law, adding 258 seats, there is an increasing consensus that enlarging Congress is a necessary step toward a more representative democracy.

Democracy stems from the Greek word “demos,” meaning people. Needless to say, a democracy relies on the power of the people. Therefore, it is essential that elected officials are capable of representing the will of their constituents. One of the most simple but effective ways to make a government more representative is electing more delegates.

Abraham Lincoln famously called democracy a “continuous experiment.” Maybe it’s time to experiment with enlarging the U.S. House of Representatives.