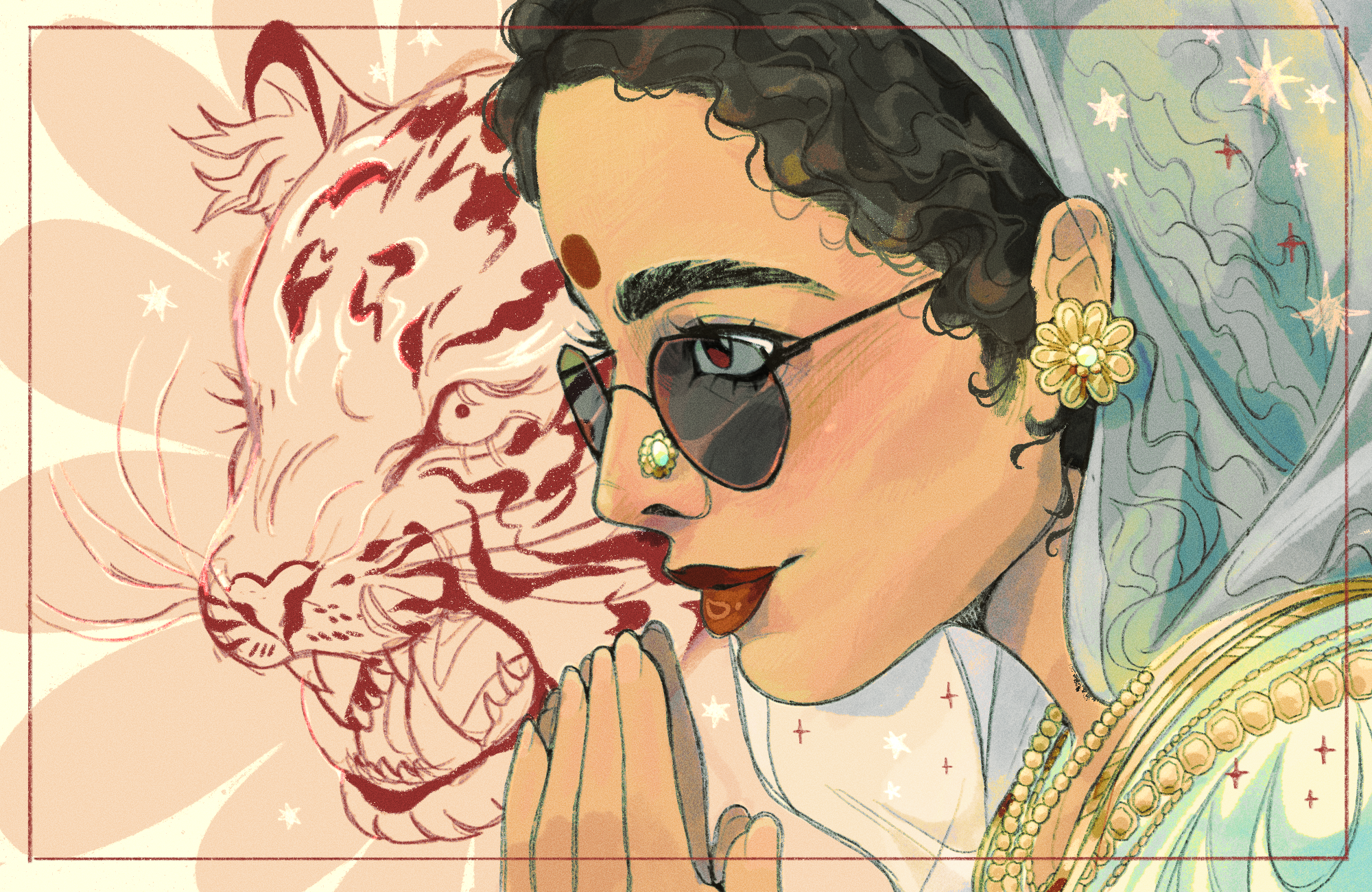

A petite lady wearing dark shades saunters to the mic at a feminist meeting in Mumbai’s Azad Maidan sports ground. She introduces herself as Gangubai Kathiawadi, a social activist and madam of a brothel in the Kamathipura red-light district.

“Everyone here probably has a job,” she begins. “Those with intelligence sell their intellect; our business is of the body, so we sell our bodies. Why is only our profession seen as immoral? You all lose your dignity once, and it’s gone. We lose our dignity night after night; it never ends.”

This is a scene from the eponymous film “Gangubai Kathiawadi,” a film from India’s Hindi-language Bollywood film industry inspired by the life of Gangubai Harjeevandas, an activist and sex worker who, in the 1960s, lobbied for sex workers’ rights. Her story is one of great tragedy, marked by trafficking and assault, but also one of triumph, as she became the de facto leader of Kamathipura and protector of its sex workers.

The film, directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali, has intricate sets and dramatic lighting — an ideal Bollywood package. However, it also manages to take Gangubai’s story seriously.

“Gangubai Kathiawadi” effectively humanizes sex workers, advocates for their rights, and shares the story of a stalwart activist, making it one of Bollywood’s most moving biopics. But, to make room for dramatic songs and monologues, “Gangubai Kathiawadi” oversimplifies the story of sex workers in India and focuses too narrowly on an individual story. Though impressive, the film highlights Bollywood’s ongoing struggle to balance gritty storytelling with the industry’s classic grandeur.

The History of Sex Work in India

Sex work has been embedded in Indian culture for thousands of years. The devadasi and tawaif systems of sex work have been prominent in the subcontinent for centuries.

In ancient South India, devadasis were teenage girls dedicated to serving the deity Yellamma. They would spend their lives leading worship and dancing in the temples while caring for the premises. While devadasis were often of higher status within the temple context, many came from lower castes and relied upon patronage from temples and wealthy elites for their livelihood. Patronage also implied sex work, and devadasis’ autonomy over their bodies was limited. The profession grew more stigmatized and exploited over the years, especially under British colonial rule, which targeted their patrons. Today, despite being outlawed in 1947 under the Madras Devadasi Act, the devadasi system continues in certain parts of South India, though less widespread than before.

While the devadasis were prominent in religious life in South India, the tawaifs held a place of importance in North India’s courts, marking another distinct but equally complex relationship between patronage, performance, and power. Tawaifs, who served as sexual partners to the ruler and his courtiers, wielded considerable political and social influence in North India. Central to Mughal culture and even more powerful during the period of Mughal decline, tawaifs were treated as entrepreneurs and cultural idols.

Like Japanese geishas, tawaifs contributed significantly to the thumri form of music and mujra form of dance, theater, Urdu literature, and the teaching of etiquette. The process of decolonization led to the disintegration of the princely states and the abolishment of the landlord system, which provided tawaifs with patronage. So, the tawaifs were forced to turn to bar dancing in metropolitan cities, where they often faced abusive dynamics.

These, of course, were not the only systems of sex work in India, but their decline over time represents a trend. Throughout the 19th century, British officials established state-regulated brothels, with sex workers recruited from rural families and paid by authorities. As British power grew in India, the public sentiment toward sex work, more specifically, interracial sex between British men and Indian sex workers, grew more negative, and efforts were made to remove state-run brothels from normal community life.

An example of one such effort is the Contagious Diseases Acts which were in place throughout the 1860s-1890s and required sex workers to undergo compulsory medical examinations to check for venereal diseases. Likewise, the Cantonment Acts governed sex work in military areas; initially, registered sex workers were allowed to operate under strict surveillance, and later, they were barred from entering the premises, eventually being restricted only to red-light districts.

Plot Analysis

In the 1950s, Ganga, played by actress Alia Bhatt, dreams of becoming a Bollywood superstar. Her boyfriend dupes her into coming to Mumbai with him to pursue this dream but instead throws her into a brothel in Kamathipura.

After being brutalized by a local goon, Ganga finds an ally in her boss, Rahim Lala, who vows to protect her. Within nine years, Ganga became madam of the brothel, earning the title Gangubai Kathiawadi, or “Madam Gangu of Kathiawar.” She runs for district president, and despite facing political challenges from a rival, she wins with the help of Rahim.

As president, Gangu protests against a local Catholic school trying to force sex workers out of the area. She enrolls the children of Kamathipura in the school, paying five years’ worth of school fees. Still, the nuns, prejudiced against the sex workers, throw the children out again, labeling them as harmful to the school environment.

This led Gangubai to make a speech in Azad Maidan, which was so popular that it got her a meeting with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to urge him to secure the rights of sex workers to equal treatment and education.

“Gangubai Kathiawadi” tries its best to balance Bollywood’s flair for the dramatic with an honest portrayal of a marginalized group’s fight for dignity, and it performs better than most, including Padmaavat, another historically-based Sanjay Leela Bhansali film that faced legal troubles for fabricating details and passing them off as historical and negatively portraying certain religious groups.

In fact, several activists praised “Gangubai Kathiawadi” because of the respect given to the protagonist and the sensitive topics it broached with tact. The publication Feminism in India lauded the film’s conversations about consent, intimacy, and sisterhood among sex workers.

The film, on the face of it, is an earnest effort to tell the story of a marginalized community and sheds light on a noble figure who isn’t well-known in India; it is a far cry from the traditional Bhansali film platforming historical narratives of kings and queens.

Part of this comes from Alia Bhatt’s performance as Gangubai; she brings much-needed emotional depth and sincerity to the role. The cinematography also deepens the film’s message. The lighting brightens in scenes where Gangubai is campaigning for the betterment of sex workers and dims in moments of oppression, hopelessness, and, curiously, love.

However, in choosing to center one woman’s dramatic rise, the film brings awareness to real struggles—especially the stigma faced by sex workers’ children, the denial of dignity, and the challenge of gaining political representation—but leaves out other systemic factors that the broader sex worker movement continues to confront such as sexual health, transgender rights, and the politics of brothel madams. It’s almost as though the filmmakers found it easier to champion a single charismatic figure than to grapple with the messy realities of sex work. By doing so, they dilute what could have been an even more eye-opening systemic critique.

Sex Work in India Today

Today, voluntary sex work is legal in India, though this does not include brothels and public solicitation, and sex workers are entitled to equal rights. The law is vague on the definition of sex work, and sex workers continue to face social stigma. This results in the denial of basic human rights for sex workers and their families. Female sex workers struggle to access healthcare, are abused, exploited, targeted by the police, and their children are often harassed.

Much like Gangubai, many activists’ work focuses on getting legal and societal recognition for sex workers, which is the first step to legal progress. Despite the work of these activists, there are still very few public resources available to sex workers, especially with regard to sexual health. India has some of the highest rates of sex trafficking, mostly internal and caused by economic disparities. To pay off debts, poor tribespeople often have to resort to trafficking themselves.

The most important message is that sex workers are not subhuman, and they are not devoid of the ability to give consent. Ayeesha Rai, a sex worker and activist with the Veshya Anyay Mukti Parishad collective, said in an interview with The World that “adult women in sex work have never been treated as adults, almost as if they did not have the ability to consent about their own work, about their lives.”

For the government to effectively stop human trafficking and empower sex workers, they first must treat them as humans and understand their basic needs.

Granted, “Gangubai Kathiawadi” isn’t a documentary; it’s a larger-than-life Bollywood film intended to do numbers at the box office. However, it does highlight a key issue in India and attempts to change perceptions of sex workers in Indian society. While there is a critical need for more nuanced representations of marginalized communities in Indian cinema, Gangubai is a solid first step for Bollywood.