“Afghanistan Fiasco Raises Hard Questions for Europe” ran a New York Times headline eight days after Kabul collapsed in the face of the Taliban’s unrelenting offensive in Afghanistan. CNN editorialized that Europe was now contending with America’s “departure” from the “world stage,” and analysts worried that the U.S. was shirking from its NATO commitments.

That same rhetoric — hysteria that American foreign policy has turned on its head — recurred more recently, when French foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian raged against a new trilateral security pact between the U.S., the U.K., and Australia, castigating the move as a “stab in the back,” and French President Emmanuel Macron furiously recalled his country’s ambassador to the United States, a sharp blow from America’s oldest ally.

These sensational newsbites detract from the underlying cause behind these flare ups between friends: a slow, but perceptible, reassessment of American strategic needs and objectives. The Obama Administration began embracing a “pivot to Asia” approach to America’s foreign policy, a trend which continued during the Trump Administration, with its Indo-Pacific Strategy aiming to elevate Asian allies, and has now accelerated under President Joe Biden.

It is not news that President Biden is prioritizing Asia: At the beginning of his tenure as president, Biden packed his team with Asia experts, and hosted Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga as the first foreign leader to visit the White House. Redefining China as the U.S.’s chief foreign policy concern and Asia as the principal arena of America’s strategic objectives is also common sense because China poses unique and growing political and strategic concerns. China’s expanding economic might, its aggressive military posture, and its abuse of the world’s economic system and international trading rules demand American attention. A tough-on-China stance is popular among Americans and is one of the few issues that bridges support between Democrats and Republicans. Policymakers can easily sell an assertive policy towards China, either as a liberal concern about Chinese human rights abuses, or using nationalistic rhetoric about China’s threat to America’s status as the world’s sole superpower.

Today’s age demands that the U.S. must shift from an imperialistic foreign policy, where America’s primary military commitments were in the Middle East and its closest allies were mostly European, to a new bipolar era, where Asian allies and multilateral groups like the Quad –– a cohort including the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia –– reign supreme, and the United States focuses on military preparedness in the Pacific region. This shift necessarily implies a reorganization of American priorities, which is an inherently difficult process. Friends will feel abandoned as old causes that were held dear for decades decline in importance.

Withdrawing from Afghanistan will allow the U.S. military to prepare for possible conflicts in the Pacific and to uphold its Asian commitments. The evacuation was conducted poorly, and better exit plans should have been established before leaving, but the fundamental choice to remove American troops, leaving Afghanistan vulnerable to a Taliban onslaught, was a reflection of the calculation that America’s interest in Afghanistan is outdated. While better planning could have softened the blow of America’s exit by allowing for more evacuees and avoided the damage to America’s reputation caused by their chaotic retreat, the pain incurred by abandoning Afghanistan’s government was inevitable.

Worries that American foreign policy is in decline following the Afghanistan debacle is misplaced. The opposite is true: America now rationally categorizes the Pacific region as more important than the Middle East. Instead of being bogged down in endless Mideastern wars with ambiguous goals and shifting objectives, American diplomatic and military resources can be more sharply targeted towards Asia.

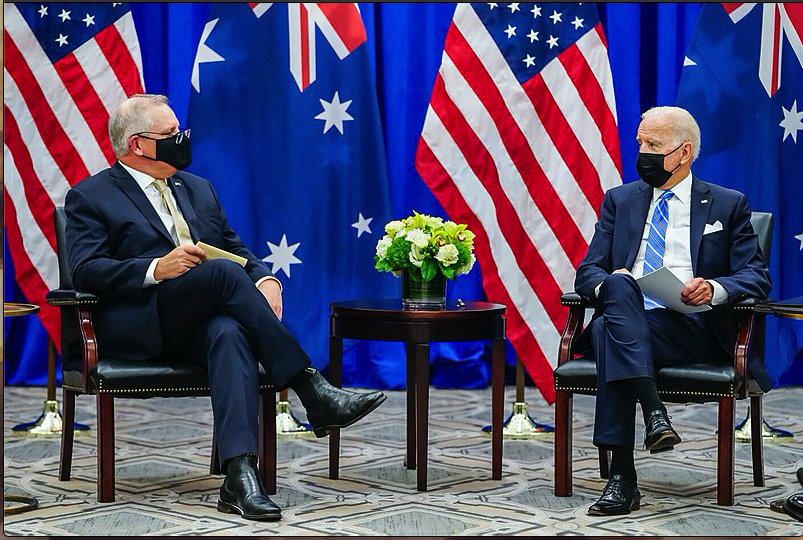

AUKUS — a new defense agreement between the U.S., the U.K., and Australia — reflects this change too. The controversy over AUKUS arose when the new deal, which provides Australia with American nuclear-powered submarines, effectively replaced a $90 billion contract Australia had signed with France to acquire diesel-powered submarines. Knowing that AUKUS would hurt France, President Biden pushed ahead with the trilateral agreement: In this new world order, the U.S. must value its presence in the Pacific more than its friendship with France. The whole affair could and should have been handled more gracefully — the Biden Administration should have courteously conferred with France, which remains a valuable ally and an active figure in the Pacific too — yet America’s outlook on its allies is fundamentally evolving from a Eurocentric model to an Asia-focused template.

The shifting tides should not spell the end to America’s relationship with Europe, nor should it produce excessive political turmoil. While America seeks close alliances in Asia, America’s historic friendship with European countries will still be important for a host of issues — from climate change, to containing Russia, to nonproliferation, and to handling Asia itself. The U.S. should undoubtedly better conduct its foreign policy to avoid crises like its shambolic exit from Afghanistan and prevent ill-feeling like the irritation engendered in the AUKUS tumult.

The pivot to Asia is bound to be painful, but it need not be superfluously excruciating. The long-talked about pivot is now in full force; the question is how to limit the collateral damage that pivoting will inevitably cause.