For centuries, the United States, a country built on the premise of religious freedoms, has been home to people of all faiths, beliefs and traditions. This ideal is evident and central to the founding of the country and the personal stories of Americans, as reflected by the decisions made by early English settlers fleeing religious persecution in the 1600s all the way up to my own Indian, Hindu grandparents moving to America for a better life in the late 1980s. While those on the Mayflower and my grandparents did not have the most in common objectively, they did hold the shared belief that in America, they could experience the freedom to practice their religions as they see fit. Yet, to one Hindu in particular, former 2024 Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy, interrogation about his Hindu faith as an impediment to his presidential qualifications was boundless.

After the Iowa caucuses earlier this week, Vivek Ramaswamy dropped out of the Republican primary race, endorsing Donald Trump for the presidency. Though the Republican primaries will progress without him, his attempt at the White House as a Hindu-American son of immigrants is significant. Certainly, Vivek Ramaswamy was not the conventional Republican presidential candidate. In a GOP increasingly dominated by Christian cultural conservatism, Ramaswamy’s Hindu faith is an outlier; it makes his campaign worth examining under this specific context.

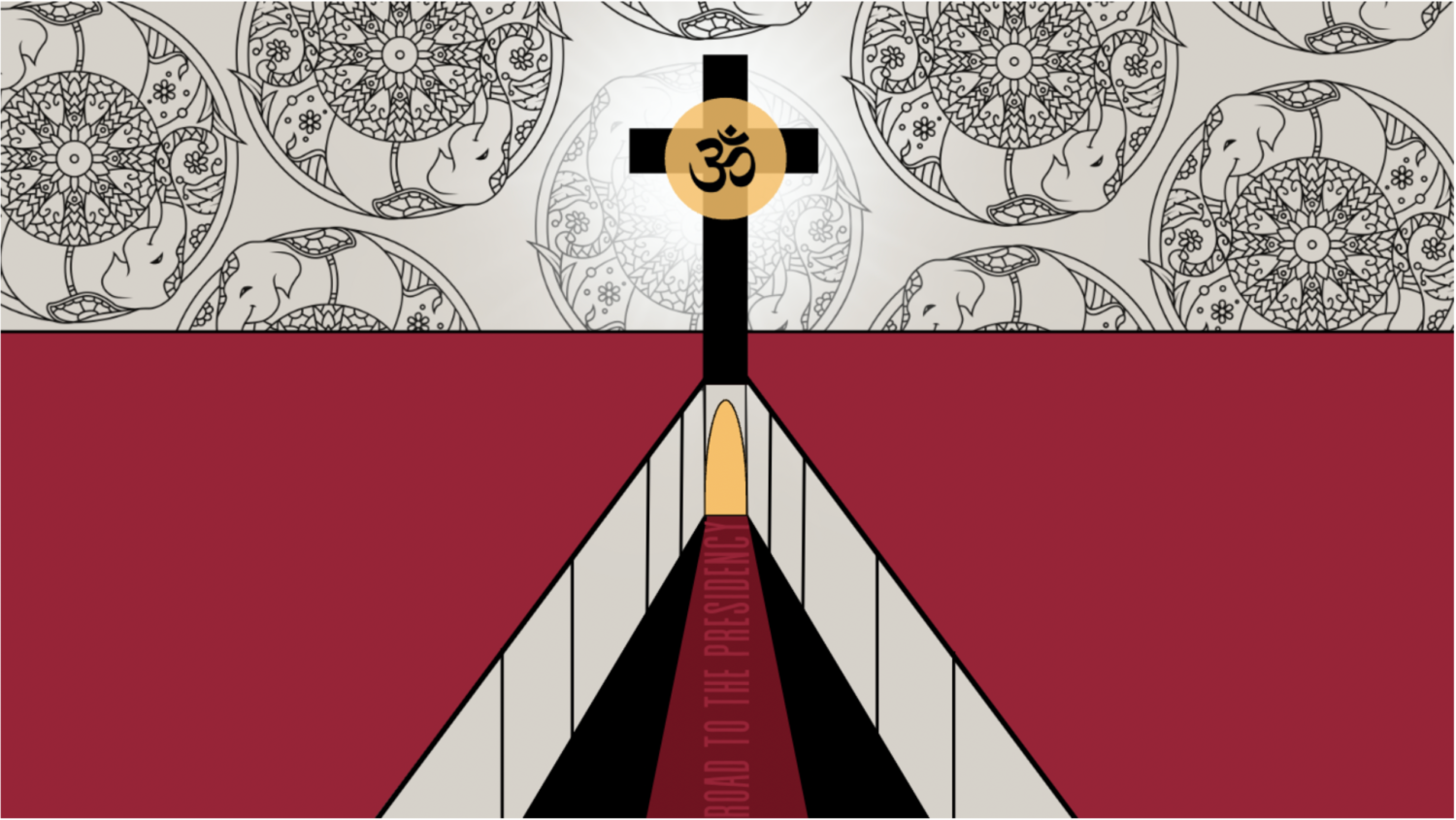

To most Christian conservatives, even before hearing his policies, Ramaswamy’s religion itself made him an unfit president. To this population, Hinduism is foreign and alienating, yet these are the people Ramaswamy needed to appeal to during his campaign. The success of his election resided in the hands of these voters, no matter how religious stereotypes may impede democracy. Therefore, in Ramaswamy’s pursuit to earn the seat of the United States presidency, he modified and equated his Hindu religion to the religious beliefs of the GOP’s large evangelical base.

Perhaps in anticipation of the religious questions he expected to be asked, Ramaswamy built his campaign upon his Ten Truths, his political decree, beginning with the clause: “God is real.” He especially bolstered this statement when asked questions on religion during the campaign trail. Ramaswamy, though he frequently affirms his Hindu beliefs, preferred to draw on Biblical stories and his fundamental belief that the United States was founded on Judeo-Christian values in his responses. Along with other conservative advocates of this viewpoint, Ramaswamy’s campaign was built on the basis that Judeo-Christian values are integral in preserving the country’s moral and ethical identity, especially emphasizing individuals’ natural rights.

Earlier in his campaign, Iowa voters asked Ramaswamy to elaborate on his religious values and views with the question, “Your first line says, ‘God is real.’ What God are we talking about?” After a campaign day filled with repeat faith questions, Ramaswamy was quick to establish a connection with his deeply Christian voters, insisting that “I’m a person of faith. Evangelical Christians across the state are also people of faith.” He often furthered his connection to Christianity by sharing his familiarity with the Bible and stories of growing up attending a Catholic school, even adding anecdotes of winning religion awards while at St. Xavier High School in Cincinnati.

When Ramaswamy could not evade answering questions about Hinduism through witty Biblical references, he resorted to drawing comparisons and establishing commonalities between Hinduism and Christianity, stating that “As we say in the Hindu tradition, God resides in each one of us. In the Christian tradition, you say we’re all made in the image of God.” More generally, it appears that Ramaswamy portrays Hinduism and Christianity as one, and pits them against other religions in the United States, declaring that “religions like ours, [unlike] new secular religions” have persisted through time.

Evidently, Ramaswamy artfully selected pieces of his faith that appeal to his voter base, “taking great care to show a certain aspect of Hinduism without talking about mysticism and polytheism, which are core aspects of the religion,” according to Karthick Ramakrishnan, founder of AAPI Data and a public policy professor at the University of California, Riverside in an interview with AP News. Ramakrishnan’s remarks are echoed by Ria Chakrabarty, policy director of Hindus for Human Rights in the same AP News interview when she states her concerns with Ramaswamy packaging “Hinduism in the family values mold, and talking about it as a monotheistic religion to appeal to the Abrahamic faiths.” Though Hinduism is one of the most welcoming religions, with immense amounts of flexibility for followers, there are still some fundamental truths of the religion that Ramaswamy overlooked in his appeal to his Christian conservative voter base. These actions, while spreading one kind of “shared-faith” message to those who could benefit Ramaswamy in politics, also spread a message of possible ingenuity to Hindu-Americans in the United States.

As a Hindu Indian-American, daughter of immigrant parents, it is disappointing to see my religion curated and presented in one political light in an effort to appeal to a monolithic community. Ramaswamy fed into this harmful messaging, but I believe he did it because he viewed these blended, “socio-politically correct” takes on Hinduism as his only path forward to winning the presidency as a Hindu candidate. It’s an added cherry on top that his identity, life story and religion supposedly vindicates the GOP of the notion that the United States is not a racist country. In an interview with The Associated Press, Ramaswamy almost perniciously flaunted how his Hindu beliefs enable him to be “an even more vocal and unapologetic defender of [religious liberty] precisely because no one is going to accuse [him] of being a Christian nationalist.” In fact, Ramaswamy tactically positioned himself in this balance of being just Hindu enough to be well-received by the GOP and also seen as a strategic choice to protect and bolster the GOP’s reputation. Regardless, this attempt fell short.

Certainly, the larger discussion on religious representation is not novel, yet to me, a young woman a part of a religious minority here in the United States, this instance does feel novel and critical as an opportunity to make space for Hindu Americans, and more broadly South Asians, in politics. It is no surprise that Americans hold Indian Americans and other South Asians to the model minority myth and stereotypes in an effort to explain our success and, dare I say, overrepresentation, in medicine, engineering, and other skilled professions. Why does this robust support and belief in competence not extend over to politics and positions of power and influence in government?

Now, let it be known that I do not share Ramaswamy’s politics or assert my confidence in his leadership. He was never fit to be the President of the United States. He claims climate change is a hoax, believes affirmative action to be a “cancer on our national soul,” supports abortion bans, and thinks racism is “not a top 50 problem” — all perspectives that I believe can only come from a place of realized, yet inexcusably weaponized, privilege. Still, the line of questioning he faced regarding his faith is non-democratic in a country that prides itself on its freedom of religion and separation of Church and State. When other politicians of more widely-known faiths are rarely asked about their religious beliefs, it feels as though those who questioned Ramaswamy’s religion often did so with the motive of equating his cultural and religious identity to inabilities, so as to ultimately bar him from political power.

Nevertheless, it is the truth that Ramaswamy’s religion is novel to the masses of America. Hindus only make up 1% of the country. This number itself was enough to subject Ramswamy to lines of questioning regarding his faith, as it was and will be the case when other politicians break norms. Conspiracy theories regarding President Barack Obama’s birthplace and citizenship, along with Islamaphobic comments on Rep. Rashida Tlaib’s Muslim identity and even questions about another GOP presidential candidate Nikki Haley’s Indian heritage, reflect similar instances where people in the minority work toward positions of political power and in the process are bogged down by harmful, weaponized lines of interrogation.

Amidst all these questions, I do take note of Ramaswamy’s decision to remain steadfast in his religion, saying “I’m a Hindu. I was raised Hindu. We raised our kids in the same tradition as well” when the opportunity presents itself. Ramaswamy, almost self-laudingly, suggests, “an easy thing for me to do being a politician to follow this track is shorten my name, profess to be a Christian and then run,” — a clear jab at Haley. Regardless, this route is the personal choice of other South Asian American candidates, and made it such Ramaswamy was the only Hindu presidential candidate in the 2024 election. While noting his disapproval of Ramswamy’s political views, Indiana University political science professor Sumit Ganguly finds him to be “gutsy for not hiding his faith or converting to Christianity for political gain.”

As the Republican party primaries continue without Ramaswamy, the principle of his Presidential run is applaudable. While Ramaswamy is not my pick for Hindu representation in politics, he is one of the few spotlighted figures with political success thus far. In states with small Hindu populations, notably those in the center of the country, Ramaswamy’s Republican campaign was people’s only exposure to Hinduism. He has made an impact. Whether Ramaswamy acknowledges this truth or not, a widespread American perception of Hinduism rested heavily in his hands.