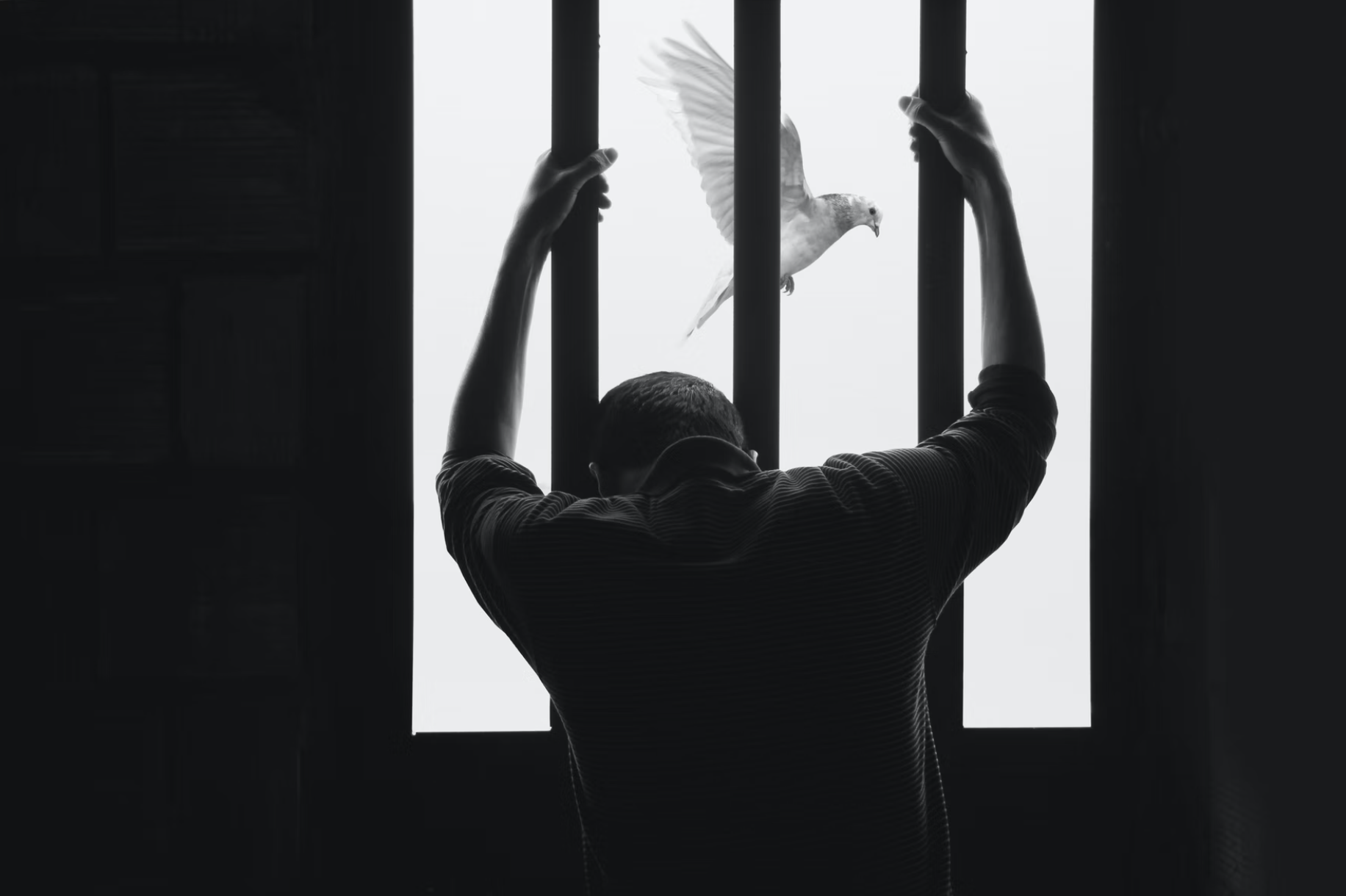

The United States claims to be “the land of the free,” yet its prison system says otherwise, representing a long history of oppression toward people of color. The United States prison system is one of the largest in the world, with American prisoners making up one quarter of all incarcerated people worldwide despite only constituting 5% of the world’s population. The legacy of slavery in America manifests through an incredibly exploitative carceral system in which Black people are still heavily controlled and exploited to generate profit for private entities against their will. The system of prison labor in particular forces people to work in inhumane conditions in a way that mirrors the attributes of slavery in America. Slavery and anti-Blackness are deeply ingrained in American institutions, and prison labor is just one of the thinly veiled systems used to perpetuate it.

The Foundations

Formal slavery in America saw its end with the 13th Amendment, which was passed in 1865. The 13th Amendment states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” This amendment outlawed the practice of slavery as it existed more than a century ago. The caveat, however, was that involuntary servitude remained legal in situations when it constituted the punishment for a crime, thereby allowing the institution of slavery to continue under another name. To this day, prisoners in America are forced to work against their will in jobs they do not want, which by definition is involuntary servitude, or slavery.

Still, the condition of prison labor is not a “loophole,” as it is sometimes labeled. This piece of the amendment was written intentionally as a way to continue the oppression of Black people once slavery was no longer a politically viable option following the end of the Civil War. The Union did not enter the war with the intention of ending slavery, as Abraham Lincoln was no abolitionist, nor did he consider himself to be one. The Emancipation Proclamation was a political tactic to undermine the power of the Confederacy, a key example of how Black freedom has repeatedly been instrumentalized in service of ulterior motives. According to Tryon P. Woods, an associate professor of Crime and Justice Studies at the University of Massachussetts, slavery has always been a cultural institution first, not an economic one. He told the HPR, “The reason for the slave’s existence was to establish who’s a human being and who’s not a human being.” The end of slavery in America, therefore, not only left labor shortages but also created a power imbalance that White people in America were not ready to give up, hence the creation of the prison system. There was no concrete prison system in America prior to the end of slavery. Black codes, which policed almost everything Black people did, meant that it was much easier for them to be brought into the criminal justice system. The first real prisons in the country were built in the South after the end of the Civil War, and to this day they have contained Black people at disproportionate rates.

After the Civil War, one of the first ways in which prison labor manifested was in the system of convict leasing. Prisoners, who were majority Black, were able to be leased by private entities for their labor. Much of this labor went to plantations, creating a very similar scenario to slavery in which White overseers were using forced Black labor in their fields. This system only served to enrich private enterprise and expand the control of the American government, as the people who were actually doing the work faced incredibly high death rates and did not see any benefits. Not only did this system clearly harm prisoners, but it also made it more difficult to later obtain safe and well-paying jobs as a free worker, meaning that Black people had very few pathways to economic success after the war. One prominent example of how the prison system in the South mirrored slavery after the war is the Angola plantation, which was converted into a prison. Prisoners were forced to work the land in much the same way that they were when it was a private plantation, and they were housed in what used to be slave quarters. Although slavery was supposedly outlawed at this point, the institutions of forced labor and oppression towards Black people were still alive and well, just under different names.

Despite much of the oppression in the American prison industrial complex being rooted in slavery, mass incarceration of Black people reached new levels in the 1970s and 1980s. The beginning of the War on Drugs in the early 1980s played a major role in the spike in Black imprisonment, even though actual crime rates dropped in the ‘70s and ‘80s. In the aftermath of the civil rights movement, the government had a particular interest in maintaining racial control. It turned to the War on Drugs, putting into place policies which have led to the state of mass incarceration today.

Prisons Today

Prisons in America today continue to incarcerate people at incredibly high rates, especially Black people, and perpetuate oppression in their communities. Today there are over 2 million people in prisons across the country, which is a 500% increase over the past 40 years. On top of this, 5 million more people are under some type of community supervision. Black people make up about two-thirds of the prison population, although they are just over 14% of the total American population. Black men are also six times as likely to be imprisoned as White men, with around one-third of Black men being expected to serve a sentence in their lifetime. In 2016, the Council of Criminal Justice also published a report stating that Black men generally serve longer sentences than White men charged for the same crime. The United States has 639 incarcerated people for every 100,000, while the country with the next highest rate, El Salvador, only has 566. This is all evidence of how America over-imprisons its minorities, moreso than any other country in the world.

The oppression, however, does not just exist in denying people their freedom. The United States also exploits prisoners for their labor, again mirroring the ways in which African Americans were exploited under slavery. Statistics on prisons can often be unclear and highly contested, but somewhere between 10 and 50% of prisoners perform some sort of labor while serving their sentences. The types of work prisoners perform vary greatly. They can be anything from general upkeep of the prison — including maintenance, laundry, or food services, which is the most common — to producing goods to be distributed outside of the prison. A small portion of prison laborers work for private manufacturers as well.

Although prison labor is often technically optional, prisoners are very easily exploited because they still have to pay for their day-to-day necessities — often at higher costs — and do not have the opportunity to look for different work elsewhere. Because of this, any job that is offered is often better than having no job at all. In some places, people can be threatened with solitary confinement if they refuse to work as well. This system of labor proves to be highly profitable for private prisons. Although these prisons only make up a small portion of prisons across America, their standing allows them to have a disproportionate influence on prison policy in America, allowing them to perpetuate the harm they are causing.

Prisons are able to save on spending by having inmates perform many of their upkeep duties, yet the government is still making a profit off of their labor. It is estimated that the American prison system makes around $500 million per year just from prison labor. Prisons sell extra goods for profit and export the goods prisoners produce at extremely low costs. Many of these products are for the government, such as signage or license plates. Additionally, prisoners earn incredibly low wages, and in some states earn nothing at all. The average minimum wage for inmates in America is 93 cents per day, nowhere near a liveable income. Joseph Lascaze, an organizer with the New Hampshire ACLU, described to the HPR how prison costs can become astronomically high, while prison wages are incomparably low. This, he said, is how prisons can oppress not only inmates, but also their families and communities, as they are forced to send money in order for imprisoned people to support their basic survival. Lascaze said, “Why is it that for 10 minutes, to talk to my family, or my nephew, or a loved one, it costs three dollars, and I’m going to get charged that $3 whether I talk the full 10 minutes or not?” This question reveals how difficult it is for inmates to do basic things, such as staying connected with their families. At the average prison minimum wage, it would take more than three days to afford just this one $3 conversation. It is unsurprising that it can be so difficult for formerly imprisoned people to rejoin society when they and their loved ones are deprived of so much.

Despite doing so much service while in prison, felons face incredible discrimination even once they are free. This includes decreased access to housing, education, public services, and voting. Perhaps the most significant and detrimental form of discrimination they face, however, is lower opportunity for employment. Many of the services inmates perform while they serve their sentences are not available as paid jobs once they leave, meaning that all of their hard work and training cannot help them once they are out. Difficulties in finding employment lead formerly incarcerated individuals to face many hardships and result in higher rates of recidivism. The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics states that 76.7% of former prisoners are arrested again within five years of their release. Recent studies, however, have shown that higher rates of employment reduce this risk. Lascaze says, “We shouldn’t have questions involving criminal conviction records be a disbarment from someone getting job interviews, or being able to effectively get a job they’re qualified to do.” He describes how a program in New Hampshire offering beautician classes to inmates has had a positive effect as it allows people to gain skills that they can use outside prison. He explains that one of the few jobs available in prison is being a barber or a beautician of some kind, so it is very important that these skills can be transferred and not let go to waste.

Prison labor provides a difficult situation because there will always be a significant power imbalance present no matter what. People’s freedom and ability to make choices about where they work or where they shop are taken from them, leaving them at an extreme economic disadvantage. Consent forms, fair wages, comparable hours to free workers, and health and safety measures do not always exist in prisons, allowing labor to become dangerously close to slavery. Many labor regulations do not apply to imprisoned people, and as such, there are no real protections in place against forced labor.

The Way Forward

It is undeniable that the United States has created an incredibly oppressive system for its imprisoned population. In order to ensure that laborers within the prison system are treated fairly, it is imperative that concrete protections be created for a fair, liveable wage, acceptable working hours, and protection agreements. Imprisoned people should also be consistently protected under United States labor laws, and should always have a path to trial for forced labor. Without this, inmates do not receive their basic human rights.

Purely supporting prison reforms, however, can be detrimental overall as all it does is improve the prison system, the very thing perpetuating White supremacy. Woods said, “Any improvement to the way the system happens, to the way the system carries out its practices, can strengthen the system of control overall by limiting any alternatives to that system.” Therefore, just protecting workers in prison is not enough to cut ties with slavery. America must rethink the role its prisons play in society in order to truly overcome the remnants of slavery and Black oppression in the system. Prison should not be a way to punish America’s most disadvantaged and place a permanent roadblock in their path to recovery, but rather it should rehabilitate people and help to reconcile them with society. Restorative justice should play a much larger role in prisons. In the context of labor, this would manifest in treating prison workers fairly, but also creating a system in which the labor they perform while serving time builds a path to full time employment once they are freed, such as the New Hampshire beautician classes program. The ultimate goal should be ensuring former inmates have a higher quality of life in such a way that they avoid the issues that caused them to end up in prison initially.

As it stands, America’s prison system, especially in the realm of labor exploitation, has incredibly dangerous implications given its history of slavery. When a country disproportionately imprisons a racial minority that was once subjected to forced labor, the question stands of whether that system is really in the past, or if it is just reimagined in the present to fit our modern sensibilities. As Lascaze says, the prison system “take[s] advantage of the freedom they can monopolize.” The control they have is about profit, but it is also about power over specific groups of people. Moving forward, we must rethink what it means to be a prisoner, or a person, for that matter, in America. Exploiting people purely for profit is a road we have been down before, and one we cannot afford to continue following.

Image by Hasan Almasi is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Interviews Editor