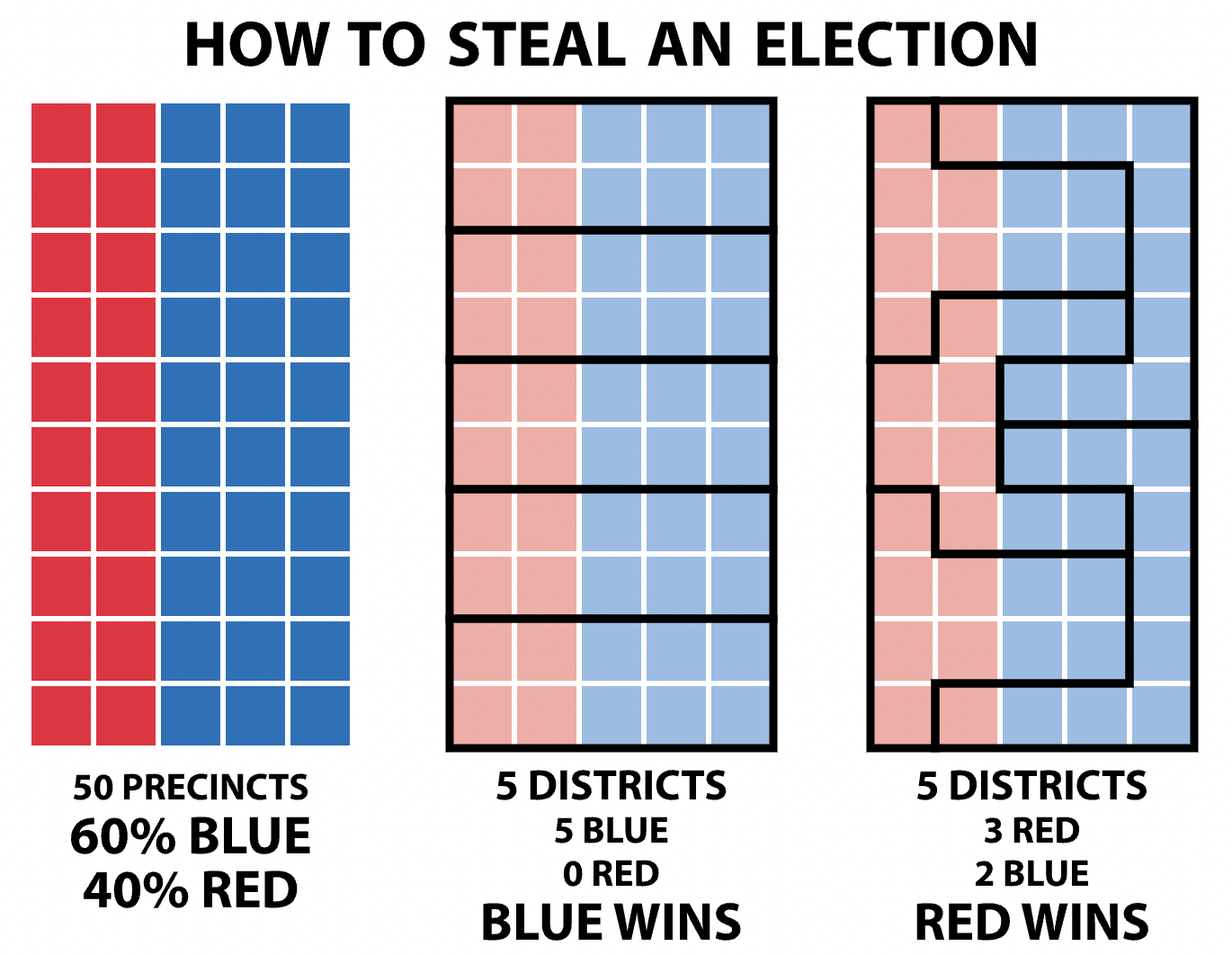

The principle of “one person, one vote” is a myth in Georgia. As a resident of the Peach State, I see the gap between the ideal of equal voting rights and the reality of widespread disenchantment with the electoral process. Georgia’s state legislature has made redistricting a partisan tool, manipulating congressional districts to effectively predetermine the outcome of elections — a process known as gerrymandering. This should not be a political process, as the purpose of redistricting is to allocate populations to sensible geographic districts.

In a state that is roughly split 50-50 between Republicans and Democrats, racial gerrymandering has led to an unequal distribution of candidates, with only one out of 14 congressional districts offering a competitive race for the political parties. Georgians cannot voice their referendum on elected officials since the congressional boundary lines have been drawn to ensure a 9-5 Republican advantage, making 13 districts relatively partisan. Meanwhile, Georgia’s federal elections have trended toward Democratic wins, most notably with President Biden’s historic 2020 victory, which marked the first time the state has chosen a Democratic candidate for the presidency since 1992. In this same election cycle, Georgia sent two Democratic senators to Washington. With the growing diversity and size of the Atlanta suburbs, the Republican Party has resorted to gerrymandering to maintain their supermajorities in statewide representation.

Although progress has been made in many states to combat racial gerrymandering, it remains a prevalent redistricting tactic frequently upheld by conservative courts. If Georgia’s federal voting patterns are shifting, the state’s congressional representation should reflect these political transitions. Gerrymandering prevents this: the redistricting process has been manipulated to maintain a GOP advantage in both the state legislature and in Georgia’s congressional delegation. In doing so, the Georgia legislature denies voters their right to decide who represents them.

The effects of gerrymandering go beyond just the partisan composition of state delegations; the procedure challenges fundamental characteristics of democratic culture regarding freedom and choice. When electoral maps are drawn to entrench incumbents and avoid competitive races, elections become a “mere ritual to verify the predetermined result,” discouraging Americans from engaging in politics and producing apathy.

This manipulation of electoral boundaries not only entrenches partisan advantages but also amplifies racial inequalities, a strategy that continues to be legitimized by conservative courts.

In many southern states, there is often only one district where a sizable minority population makes up the majority of voters, despite a large minority population state-wide. Public interest and activism against the practice have soared after the 2019 Supreme Court decision to limit federal courts from blocking this infringement on American democracy. The ruling barred federal courts from ordering states to draw new maps on account of partisan biases, setting a much stricter standard of what violates the “one person, one vote” principle or adequate evidence of racial gerrymandering for a map to be redrawn. Therefore, a federal court cannot attempt to “reallocate political power between the two major political parties.” It can, however, decide cases of population inequalities within districts and racial discrimination.

While federal courts are now more limited in redistricting decisions, the Supreme Court continues to make rulings in various gerrymandering cases. However, the decisions have proven to be inconsistent in their approach to fair representation. In 2023, the Court delivered a win to anti-gerrymandering activists, ruling that Alabama must draw a second majority Black district under the Voting Rights Act. The map in litigation had a single majority African-American district even though Black voters make up 27% of the state’s voting-age population.

Yet, the Court does not always side with civil rights leaders. In a 2024 decision, the Supreme Court rejected the argument that South Carolina’s congressional map was biased against minority voters. According to the majority opinion by Justice Samuel Alito, the NAACP failed to prove the district lines were drawn based on racial factors, as partisan concerns appeared more likely. Yet, 30,000 African-American residents of Charleston were shifted out of their home district through gerrymandering. Conservative courts continue to protect states like South Carolina, allowing them to avoid implementing nonpartisan redistricting practices. While some rulings, such as the one in Alabama, have weakened the extent to which racial gerrymandering occurs, the practice remains a cancer in the American political system.

Georgia voters experiencing vote dilution were also not offered any form of justice in the court system. While new majority Black districts were drawn in the state Senate and the state House, Republicans looked at other parts of the state to increase their voting power and balance these alterations. The 7th Congressional District in suburban Atlanta was made more favorable for conservatives. This is because the Voting Rights Act shields minority voters but not the “tinkering [of] Democratic-held districts with white majorities or where no ethnic group is in the majority.” While not as brazen as South Carolina’s redistribution of voting populations, Georgia legislators carefully adjusted district lines to maintain political power.

The three cases previously noted demonstrate the unpredictable nature of the United States judicial system, specifically when cases involve voting rights and disenfranchisement. A more consistent response to these disparities has been found in independent commissions across the country. For instance, in Michigan, the GOP-drawn map relied on diluting the African-American vote in Detroit to increase Republican seats across the state. The suburbs of Oakland and Macomb were combined with parts of Detroit to help the Republican Party gain a higher proportion of their likely voters and carry the congressional seats. However, the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) combatted racial gerrymandering by allowing similar communities to be together. For example, the 6th, 13th, and 14th Districts are “now set to be in the suburban areas of Oakland County and Macomb County [to] increase urban representation.” A truly proportional map was formed by allowing the MICRC to make the redistricting decision rather than the state legislature.

So what can be done in the Peach State, my home, Georgia? Perhaps a similar redistricting reform ballot initiative proposed in Michigan could change the tide for us and the rest of the Deep South. These proposals are supported by majorities of members of each political party, and are effective in screening for partisan maps since commissioners and legal experts are responsible for reviewing the fairness of district lines drawn by mapping experts. A proposed ballot initiative in Ohio suggested using a 15-member citizen commission with five Democrats, five Republicans, and five independents. A similar structure could be proposed in Georgia and other states, with districts still drawn by a biased legislature.

While the recent Supreme Court decision in South Carolina was frightening for our democracy, independent commissions remain successful in remedying hope for fair representation. Racial gerrymandering has been dealt numerous blows in places like Alabama, but it remains a key threat to society’s bid for fair rule and accountable politicians. Georgia, too, stands at the crossroads, as ongoing legal challenges attempt to formulate an outcome similar to the Supreme Court order for Alabama to redraw its biased districts.