“Would you get a COVID vaccine if one was released in the near future?” I asked Myla Kreider, of Palmyra, Maine. “Absolutely not,” she responded. Jenny Hall, of Albion, Maine, had the same response. “I just feel like there’s not enough data, and I don’t know what the long term effects would be, or the efficacy,” she told the HPR. Unexpectedly, neither Kreider nor Hall is anti-vax. Their children have received the full vaccine schedule.

These women are not alone. Some rather shocking polls have been released recently: In September, Pew reported 49% of Americans would not get a COVID-19 vaccine, an 80% increase from their May poll. In October, CNN reported 45% of Americans would not get a COVID-19 vaccine. The anti-vax movement has seen a resurgence in recent years, but its scale gave no indication of such a massive rejection. As we inch toward a full year of this pandemic, the promise of a vaccine has been painted as the light at the end of the tunnel. But a vaccine does not help us reach herd immunity if Americans refuse to receive it.

Although we can frame the current issue with the ongoing anti-vax movement and the increasing politicization of science, in order to address skepticism about the COVID-19 vaccine specifically we must understand what makes it different. Namely, the group is more diverse, and they have a better argument. Trust in public health experts and in science as an institution rests precariously on the way COVID-19-anti-vax is handled. That leaves us asking, in true 2020 fashion: What now? We must consider and provide individualized messaging for each type of COVID-anti-vaxxer, but more importantly, we must maintain a high level of transparency and clarity to leave the pandemic with networks of trust intact.

The Old Anti-Vax

Religious anti-vaxxers existed even before the first true vaccine in 1796. With the campaign against the smallpox vaccine, the group expanded to those with anecdotal evidence of harm or lack of trust in medicine. As vaccines became more heavily regulated and potentially mandated, some Americans declared them an affront to personal liberty (as did some British citizens).

Anti-vaccination sentiment rises and falls. After a report claimed the pertussis vaccine caused 36 neurological problems in the 1970s, there was a massive decrease in uptake and a severe outbreak in Britain. In response, the government implemented financial incentives for doctors who vaccinated a quota, and released a reassessment of vaccine safety. The combination successfully increased vaccination rates to effective levels.

The most recent anti-vax surge was catalyzed by Andrew Wakefield’s now-retracted publication in “The Lancet” which claimed a causal link between the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine and autism. The U.S. vaccine injury tribunal found, based on research and the testimony of high-profile scientists, that the proposed link between vaccines and autism was not credible. However, the petitioners were unconvinced by what they saw as a single powerful establishment, the government and scientific establishment, squelching those willing to speak out against injustice. Celebrity endorsement increased the fervor. Subsequent declining vaccination rates caused measles outbreaks and resulted in California’s mandatory vaccination law.

Financial incentives for doctors and mandates, although perhaps ethically questionable, seem to have been effective in combating anti-vax sentiment. Only presenting scientific facts, on the other hand, has been less successful. As Anna Kirkland states in her analysis of credibility in the MMR trials, science “does not have a magical power to change minds,” and often results in a knee-jerk hardening of previously held beliefs. Instead, effective pro-vaccination messaging shows graphic injury, particularly to children, which could be prevented by vaccination.

The New Anti-Vax

Since old anti-vax rhetoric — minimizing the disease threat, claiming the vaccine causes illness or does not work, and claiming the vaccine is part of a conspiracy — is resurfacing with respect to the COVID-19 vaccine, we might be tempted to respond with pro-vaccine messaging that has worked in the past. However, we must adjust for two reasons: The people are different, and the process is different.

The People

There are, of course, the familiar anti-vaxxers, who spoke up as early as February with concerns about a mandatory vaccine. There are also new groups. One is connected to far-right extremism and conspiracy theories (about the virus and otherwise). The other, termed “vaccine-hesitant,” is more surprising. It includes members of the opposite demographic — highly educated, liberal, not libertarian — who are concerned about the safety of the expedited vaccine development process, especially under President Trump. A Pew poll supports the existence of both new categories. While a majority of those unwilling to get a vaccine are Republicans, 42% of Democrats agree with them, and unwillingness to vaccinate is tied to lack of confidence in its safety.

Parting COVID-anti-vaxxers into two groups which slot neatly into our current party split is easy, particularly in light of the overt politicization of the issue during both presidential campaigns. On the right, President Trump promotes conspiracy theories. He said the virus will “go away without a vaccine,” claimed that hydroxychloroquine is an effective treatment, and suggested Americans inject disinfectant. On the cautious-left, Kamala Harris said “if Donald Trump tells us to take [a vaccine], I won’t,” and Chris Wallace pointedly asked Joe Biden if his campaign was contributing to the widespread fear of a vaccine.

Off the debate stage, in the lives of real Americans, the issue is more complex than red against blue. Some fall into a “middle ground,” making their own risk assessment about the vaccine, politics aside. Hall said “I feel healthy. I feel that I’m not immunocompromised. So if I’m going to get this virus, I think I would have a chance to fight it — as opposed to getting the vaccine,” which she worries might have unknown adverse effects. Hall is otherwise pro-vaccine, and she does not support Donald Trump.

Kreider holds a similar view: “I think you’ll see a lot of people that will be supportive of [a vaccine] because there are a lot of people that are very afraid of COVID. And it’s not that I’m not afraid of the disease — I think it needs to be taken seriously, and I think there are precautions that we need to hold.” However, she believes the vaccine is “far too rushed,” and she made it clear that individuals should be able to make their own choices relating to the virus. “Do I [not wear a mask]? No. Do I think people should be damned because of it? No!”

The Process

Having identified who is concerned about the vaccine, we can turn to what there is, or is not, to fear.

Operation Warp Speed, the collaboration between various departments of the federal government and industry, impacts the speed of development but not the speed of approval. “Rather than eliminating steps from traditional development timelines, steps will proceed simultaneously,” the Department of Health and Human Services website states, which “increases the financial risk, but not the product risk.”

The change in rigor of requirements for approval would come with an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). An EUA allows use of unapproved medical products during a public health emergency when there are no alternatives. EUA requirements are based on a risk-benefit analysis, the specifics of which for this case were recently debated and eventually published. The most contested factor was the required follow-up time, how long vaccine companies must monitor vaccinated individuals before the EUA is approved. Follow-ups for a normal vaccine run at least 6 months, and often up to 3 years.

The report specifies two months (also recommended by experts), which at the time of publication took the promise of a vaccine before election day off the table. That should increase public confidence. So should the fact that the committee session reviewing the vaccine materials will be almost entirely open, excluding possible proprietary information related to manufacturing.

That being said, public health experts are asking ethical questions about an EUA, and some have stated outright that we should proceed under expanded access (usually used to make treatments available to very ill people, notably during the AIDS epidemic) rather than EUA status. Two of the leading vaccines are gene-based, a totally new technology that has never been used in an FDA approved vaccine. Anti-vax individuals are backed by evidence more than ever before. Which begs the question: Could they be right?

Looking Forward

Let’s go back to basics. Pro-vaccine social norms matter. Vaccinations work best as a tool to reach herd immunity, not an individual preventive measure. When a population reaches the herd immunity threshold, there are so few people who can contract the disease that it spreads very slowly. This protects people who have chronic illness, are too young or old to be vaccinated, or whose vaccine was not effective. Thresholds typically fall between 70% and 90%. One projection of the herd immunity threshold for COVID-19 is 66%, but many experts say we do not know enough about COVID-19 to make a conclusive statement.

If we rely on vaccination to reach herd immunity, we must convince more people to vaccinate than are currently willing. For the old anti-vaxxers, graphic injury-focused messaging worked. Unfortunately, that will likely prove ineffective here. The vaccine must be taken by many who would likely experience asymptomatic COVID-19, who would face a fatality rate below 0.05%. Compared to commonly vaccinated for illnesses such as meningitis, which has a fatality rate of 10% and symptoms like limb loss and brain damage, COVID-19 is simply less scary for most age cohorts. Influenza is the most similar commonly vaccinated-for illness, but the uptake is low, just 45% in 2017-18. And the flu vaccine itself is not the subject of public doubt.

If convincing individuals to vaccinate is the right thing to do, how would we do it? Andrew Heinrich, of the Yale School of Public Health, said sequencing will be critical in an interview with the HPR. He suggested offering the vaccine to vulnerable communities first, such as health care workers and individuals from hardest-hit geographical areas, who will “view very differently the prospect of getting a vaccine because of the urgency their community feels.” As others see these groups vaccinated, Heinrich believes trust in the vaccine will grow. This strategy also mitigates the moral dilemma, because there will be more time for the vaccine to gain a positive track record before the unwilling are urged to take it.

If major hesitancy remains after people start getting vaccinated, we should consider the four sects of COVID-anti-vaxxers individually and target messaging to each.

First, the “old anti-vaxxers” could be a lost cause. Giving a group which already did not trust the system renewed (and more legitimate) reasons for their beliefs does not bode well, especially when traditionally effective messaging will not suffice. The good news is that with a 90% effective vaccine, a fringe anti-vax group should not disrupt our ability to reach herd immunity.

Second, for the “vaccine-hesitant,” focus on the new president and the relative safety of the vaccine. Also, add reminders of the social responsibility to save lives, current social norms around pandemic behavior (much like the initial lockdown messaging), and already firmly held beliefs about why vaccination is the right thing to do.

Third, the “conspiracy theorists” might respond well to an appeal to economics. While perhaps they do not believe in COVID-19, they do believe lockdowns have taken a massive economic toll on the nation. Heinrich suggested public health officials explain that “this is what we need to do to get back to work— [many people] might acquiesce under that circumstance.” In addition, a reminder of how the speedy vaccine process represents the best of American ingenuity and economic prowess (Pfizer’s headquarters are in New York, Biontech’s Massachusetts) might strike a nationalist chord. Or, posing vaccination as a statement of American toughness might do the trick. If these people do not fear the virus, they should not fear the vaccine, either.

Fourth, the “middle ground” group requires clear communication of convincing data showing the vaccine makes sense for them. They, too, might respond well to “getting back to work.” Finally, this group would likely appreciate feeling heard by decision makers, so that public health decisions seem less broad-stroke paternalistic and more common sense. Kreider believes that in her home state, Maine, “shutting down is very, very harmful and shutting down without having a good, solid plan is not good for people.” Politicians need to think through any future shutdown plans, she concluded.

What if we convince these groups, but issues with this vaccine destroy the already tattered trust in public health officials and the scientific process? Andy Slavitt, former acting administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, put it this way: “Done right, vaccines end pandemics. Done wrong, pandemics end vaccines.” This is why, no matter what techniques we use to convince people to receive a vaccine, they must be accompanied by straightforward information.

When I asked Hall what she could tell me about the EUA, she said, “I do not know much about it at this point. I’ve done a little bit of research, but I don’t know exactly everything that’s entailed and what their research is.” The FDA’s new guidelines are public, but they are not designed for a layperson. Now and when the vaccine is released, we need simple, honest discussion of what scientists know and what they do not. That, not partisan blustering, is what builds and maintains public trust in science, and what allows it to function in its highest capacity to improve our health and our lives.

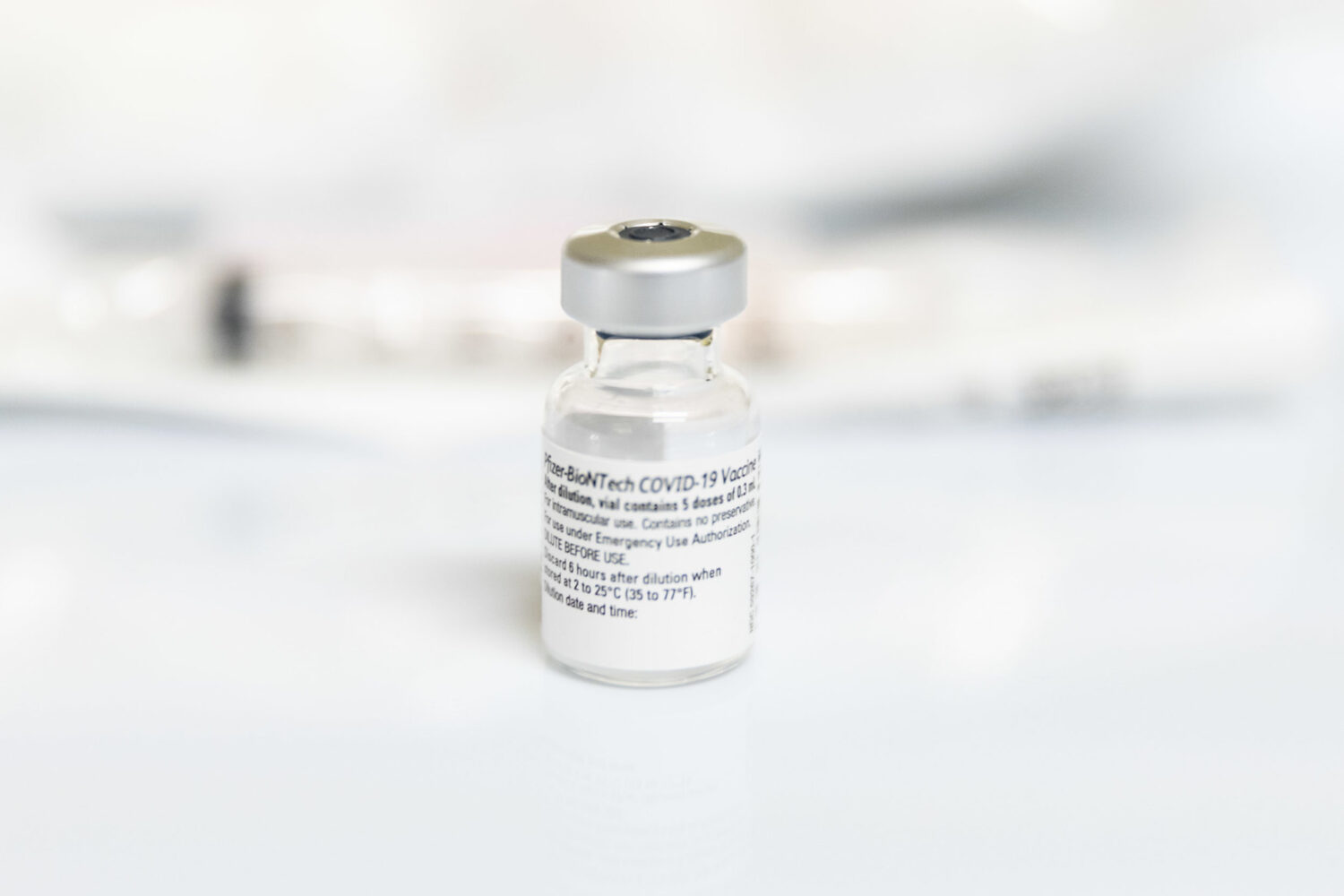

Image Credit: “COVID-19 immunizations begin” by Province of British Columbia is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.