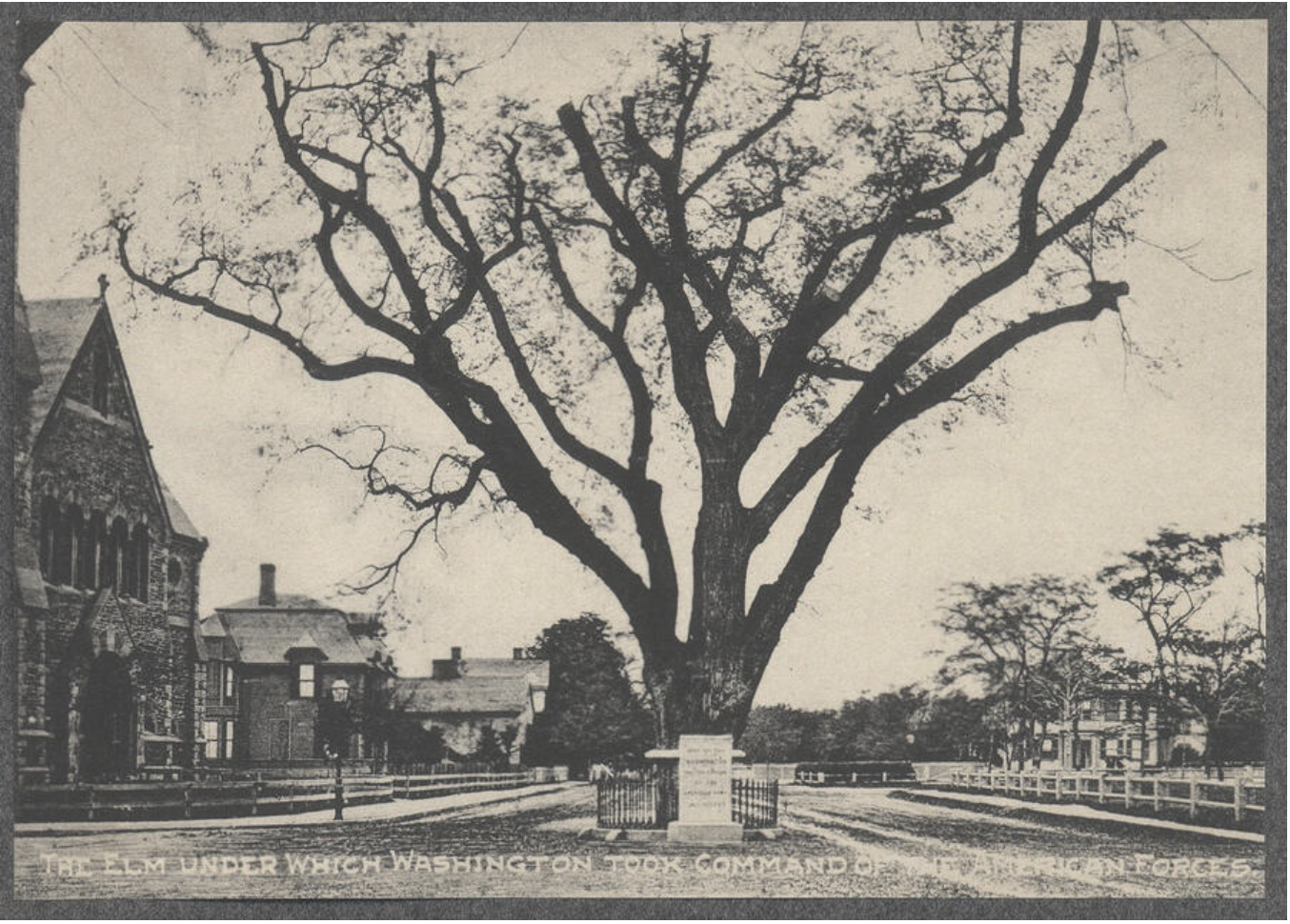

In Cambridge Common, the large public park next to historic Harvard Yard, a large elm tree stands with a small metal fence around it. Under the tree is a large gray slab, almost headstone-like, that reads:

Under This Tree

WASINGTON

First Took Command

of the

AMERICAN ARMY

July 3rd, 1775

For much of Cambridge’s history, this tree, the Washington Elm, held tremendous significance in the city’s consciousness, and in the nation’s as a whole. Legend has it that iconic American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who lived just up the road, wrote the words for this monument.

Cambridge residents gathered around the tree at the start of the Civil War. During World War II, a piece of the tree was given to the president of Peru as a symbol of American strength. Saplings and grafts from the original tree have been planted all across America, from Olympia, Washington to Oakland, Maryland to Austin, Texas.

Today, most of my Harvard classmates, even most of my friends who study Government or History, have never heard of the tree — even though it’s right across the street from their classes. The ones who have certainly couldn’t tell you its intricate, fascinating story. They’re not alone. For the most part, the Elm has faded into the mulch of history.

The Elm’s story is a towering reminder that at a time when the United States is reckoning so intensely with the monumental legacy of the Civil War, both figuratively and literally, Americans seem to have paid less attention to monuments to the Revolution.

Why? It’s unclear. Perhaps the Revolution’s ideological battle is just not as relevant to today’s national issues as the questions that resulted in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Perhaps the war was just too long ago.

Or perhaps, as the Elm’s story actually suggests, the Revolution’s legacies have just gotten a bit harder to see.

Sprouting: The Early History of the Washington Elm

The Washington Elm in Cambridge Common today is not the real, original tree.

The real Elm fell over sometime in 1923, when workers were trying to trim pieces of dead wood off of the top of the tree — ironically, to keep it from falling over.

The exact date of the tree’s demise is unclear. Harvard’s records list the tree as coming down on Oct. 26 of that year, but a contemporary issue of the New York Times claims that it happened on Aug. 13th.

The Elm was estimated to have been somewhere between 204 and 210 years old, and it was definitely on its last limb. Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum newsletter said that the tree was so dilapidated, sitting in the middle of the road near electrical wires, that it was “for a long time a menace to the public.”

The City of Cambridge tried valiantly to save the tree for many years. However, its position on an island in the middle of Garden Street made it especially vulnerable to car exhaust. If traffic didn’t kill it, the librarian at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum told the HPR, Dutch Elm Disease would have taken it out a few years later.

After the original tree fell over, a sapling of the iconic elm was planted in the Common by Vice President Charles Dawes on Apr. 19, 1925. That tree is the one that stands in Cambridge Common today. It is located within the boundaries of the park, likely to prevent the traffic-based damage that plagued its parent.

On July 3, 1925, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Washington’s taking command, President Coolidge gave a speech in Cambridge not far from the tree.

Standing Tall: The Elm, Cambridge, and Harvard

The Elm was the gravitational center of Cambridge for generations.

In fact, some believe that legendary preacher George Whitefield, a leading figure of the Great Awakening religious movement, gave a speech in 1746 underneath the tree which eventually became known as the Washington Elm — 29 years before George Washington arrived.

Jared Sparks, the President of Harvard from 1849 to 1853, is the most notable proponent of this theory. In his diary, Sparks makes reference to a man who “heard Whitfield preach in the open air under the tree which is now known as the ‘Washington Elm.’” Others, however, claim that Whitfield’s speech was actually given under the Elm right next to Washington’s tree. Regardless, the Elm was clearly a central fixture in Cambridge colonial life long before Washington arrived.

In the aftermath of the Revolution, the Elm remained relevant. In fact, the most unique development in the history of Cambridge’s relationship with the Elm happened on the afternoon of Apr. 27, 1861.

At that time, the Cambridge Chronicle reported, Cantibrigians had “suddenly awakened from a dream of security and found [themselves] in a war that [seemed] destined to take its place among the great events of the world.” Civil War was looming.

On that particular afternoon, unplanned and unprompted, “almost everybody in the streets appeared to be traveling towards one point — the Washington Elm,” the Chronicle reported. Businesses were suspended while the city held an impromptu meeting under the historic tree, and all of Cambridge deliberated on how best to help the Union prevail.

“The venerable elm was decorated with ancient regimental standards, and a shield of liberty, and draped with flags,” the Chronicle wrote. Both Massachusetts state symbols and a Star Spangled Banner were put among the branches. The Elm became the star of the festivities, a beacon of civic and national unity during uncertain times. With the Union facing an existential threat, Americans in the 1860s fell back on physical monuments to the history of their nation — in Cambridge, no monument was more tangible than the Elm.

During the ensuing Civil War, the Elm became associated with even more classic American traditions. Most notably, in 1864, when the Harvard University Base Ball Club was formed, its inaugural practices were on the Common right next to the Elm.

36 years later, the Elm remained a symbol of American pride, albeit slightly more in Harvard’s orbit. In the summer of 1900, Harvard welcomed a group of Cuban teachers to campus for a summer school program that was designed to push pro-American propaganda on Cubans, since Cuba had recently come under American control after the Spanish-American war. On July 4 of that year, the teachers “paraded” through the Yard and to the Common, where they posed for pictures in front of the Elm and listened to a patriotic speech.

When General Baron Tamemoto Kuroki, head of the Japanese Imperial Army in the Russo-Japanese war, visited Harvard on May 23, 1907, the Elm was a stop on the tour. These two events suggest that at the turn of the century, the Elm was key to Cambridge’s conception of its place in American history. More broadly, they also suggest that the Revolution was inseparable from America’s understanding of its own history.

Composting: The Elm’s Death and Local Memory

The Elm’s passing in 1923 triggered a wave of nostalgia throughout Cambridge.

Many of the city’s residents were distraught. Some grieved in strange ways, including one man wrote to the New York Times to suggest that “chemists, surely, could preserve [the Elm] from decay.” He even suggested “trimming [the tree] down and coating it in heavy, impervious paints, or a possible masque of white cement.”

Others were more enterprising. The Cambridge Parks Department’s annual report from 1924 states that on the day that the tree toppled, hundreds of amateur souvenir hunters arrived, all vying for a part of the tree. Incredibly, the report claims that one woman brought along a saw, which she “threatened to use … on anyone who dared to prevent her from getting a piece of the wood.”

After dispersing several other (less violent) souvenir hunters, the city government took over the distribution effort. Motivated to make the tree’s death “an object lesson in patriotism for the whole country,” the city distributed about one thousand pieces of the venerated elm across the nation. The tree’s main trunk was divided up and sent to the governors of each of the 48 states — with the most important piece going to Washington’s estate at Mount Vernon.

Today, chunks of the original Elm are all over the nation. The Henry Ford Museum in Michigan has one. Somehow, even Harvard’s arch-nemesis in New Haven got one. However, many of the tree’s fragments have stayed close to home. Cambridge City Hall features several chunks of the Elm’s hallowed wood. Most years, at least one Cantibrigian discovers some of its hallowed wooden remains in an attic or garage, the group History Cambridge told the HPR. Even the city’s seal contains a large drawing of the tree that is the same size as city hall.

Of course, Harvard’s libraries also harbor several pieces of the Elm. Harvard’s most famous pieces of the tree have been carved into a picture frame and a book cover that feature beautiful engravings of the Elm.

Harvard held so many pieces of the tree that it was willing to give some away. When Peruvian President Manuelo Prado visited the university in 1942, he was presented with a piece of the original Elm by Cambridge Mayor John J. Corcoran, a gesture that abounds with historical and diplomatic significance. Since this visit was during World War II, the gift was likely meant to represent a piece of America that the Peruvians could take back with them. (In fact, Prado was the first sitting South American President to ever visit the United States, according to The Harvard Crimson.)

In the same year, a mile and a half down the road from the Common, Cambridge opened what is today the second-oldest public housing project in the country, and named it after the tree: The Washington Elms.

Today, just across the street from the Common stands the Sheraton Commander hotel, named for Washington’s taking command of the Continental Army under the Elm. The columns at the entrance of the building were inspired by the architecture of Mount Vernon. The hotel also has a statue of the general outside, labeled without his name — the caption simply reads, “The Commander.”

Blossoming Anew: The Propagation of Washington Elm Descendants

As its status grew as a landmark, the Washington Elm’s influence spread far from its roots in Cambridge.

In 1902, the University of Washington in Seattle planted a scion of Cambridge’s Elm on the university’s campus; today, there is still a descendant of the tree on the school’s campus. Apart from Cambridge, UW is probably the most proud keeper of a Washington Elm descendant. In fact, UW Magazine once claimed that the Elm currently in Cambridge Common was a result of grafting their tree in Seattle, but this claim seems unlikely because the article’s dates don’t line up with other timelines.

Regardless, the University of Washington started a trend: Washington Elm grafts, scions, saplings, and clones were planted all across America in the early twentieth century. In the 1930s, Harlan P. Kelsey, of East Boxford, Mass., sold what he claimed to be descendants of the Elm. Kelsey claimed that pieces of the original Elm were grafted and planted in front of the Wellesley Public Library, about 12 miles from Cambridge Common, which were then grafted by Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum. Some of those second grafts wound up in Kelsey’s hands. His company would then graft the trees for a third time before sending dozens of them to sites around the country.

One such tree was placed in Bratenahl, Ohio, just outside of Cleveland. Bratenahl’s Historical Society was kind enough to send the HPR the materials that came with their original copy of the Elm. Interestingly, the promotional materials that the town received with their sapling said that “probably no tree in the world was or will ever be more well-known and revered than the Washington Elm.” Hyperbole, probably, but it’s nevertheless an interesting insight into the degree of prestige that the tree held in the early 20th century.

The village of Bratenhal planted their tree by their local public school in 1931, and it’s now been dead for over 30 years. Even when it was living, Bratenahl forgot about their tree; they placed a plaque next to it in 1968 to prevent forgetting again.

One afternoon, I used Google to look for other cities and towns with Washington Elm descendants; after a few hours of searching, my list was quite long. Most of the trees were planted in the 1930s, often with help from local Daughters of the American Revolution chapters. Many were planted in 1932 to commemorate Washington’s 200th birthday. It is unclear how many of them are connected to Kelsey’s company.

At least three state capitals had Elm descendants planted on their grounds. Olympia, Washington still has a tree that is closely related to the University of Washington’s tree described above. There is another in Carson City, Nevada. Austin, Texas removed its tree in 2000 due to “storm damage and advanced decay.” The Texas State Preservation Board, which managed the tree, could not be reached for comment. Though not a capital, the legendary Golden Gate Park, which lies next to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge, also has a descendant of the tree.

A Washington Post article from 1929 claims that a woman, Mrs. Dorsey, gifted descendants of the Elm to historic Washington-related sites, including Mount Vernon, Valley Forge, the governor of Maryland’s residence in Annapolis, and Washington College in Chestertown, Md. Unfortunately, it is uncertain whether any of these locations actually received a tree.

Like in Bratenahl, schools were a popular spot to plant Elm descendants. At least four were planted at public schools in the Chicago suburbs. As of 2011, Northern Arizona University’s Elm was still standing, though it was threatened by European Elm Scale, a deadly insect infection. The University of Tennessee’s flagship campus at Knoxville had an Elm that was cut down by the Department of Transportation in the early ‘90s to make way for a highway.

Other Elm descendants lie in less visible places. One sits in a parking lot in Loveland, Colo. Another can be found next to a hospital in Oakland, Md.

Importantly, several “Washington Elms” around the country claim no relation to the Cambridge tree at all, instead espousing their own connections to our first President. Palmer, Mass., has a “Washington Elm” that the Commander supposedly rested under. So do Lexington, Mass., and Hohokus, N.J. Perhaps the American psyche just loves associating our first president with trees.

Decomposing: The Elm’s Disappearance from Memory

Remarkably, despite all of this history, the Washington Elm in Cambridge disappeared from the city’s collective memory by the middle of the 20th century. Indeed, the last time that the words “Washington Elm” were casually included in a Harvard Crimson article was 1950. In that article, the site where the tree once stood was used to orient the reader: “The driver rolled slowly over the spot where the Washington Elms once stood, and wheeled on into residential Cambridge,” wrote John J. Sack ‘51.

Since then, the tree has only been mentioned twice in the Harvard Crimson. Once, last year, it was referred to as “the elm where Washington had taken command of the Continental Army,” suggesting that the name recognition of the term “Washington Elm” has evaporated from campus. The other mention, in 2016, mentions the tree in passing and incorrectly tells its story.

The campus newspaper echoes a broader trend that I observed while preparing this project: Nobody knows about the Elm. When Harvard undergraduates in two different seminars, each consisting of 12 students, were asked about the Elm, not one student said they had heard of the tree.

Most of my politically- and historically-inclined friends didn’t know about the Elm. Most of my professors didn’t, either. Many were shocked to learn the Elm’s story, especially since it allowed them to understand the namesake of the Sheraton Commander hotel that they often passed by.

Today, at the Sheraton Commander, the hotel’s staff still tells incoming guests that the hotel is named after Washington because of his taking command across the street. Even the receptionist at the front desk, however, didn’t know the details of the Elm’s story when I asked a follow-up question.

The Elm’s reputation has faded outside of Harvard, too. In 1960, a group of disabled Boston veterans presented a gavel made out of the Elm to President Eisenhower. This was undoubtedly a lovely gesture. However, the information that the group included about the Elm was very inaccurate; for one, they claimed that a windstorm blew down the original Elm in 1936, 13 years after the original tree actually died. This misunderstanding shows the extent to which the Elm had faded from popular consciousness today.

Incredibly, the only substantive reference to the Elm’s story after 1950 can be found in an old Western television show. “Death Valley Days” released an episode in 1957 (partially based on a true story) titled “The Washington Elm,” where a Boston native dreamed of grafting the tree and bringing it out to Washington state.

Shady Stuff: Controversy Surrounding the Washington Elm

The history that I’ve presented so far is woefully incomplete. The original Washington Elm, the one that fell over in 1923, has a big secret. Despite being the subject of presidential speeches, diplomatic missions, and generations of Cambridge community activities, it’s not the tree under which Washington took command of the Continental Army. In fact, there never was such a tree.

The only written account claiming that General Washington took command of the Continental Army under the particular tree that stood in the Common until 1923 was the so-called “Diary of Dorothy Dudley,” which was proven to be a forgery sometime in the 1800s. Once the Diary was disavowed, there were no remaining primary sources that actually linked Washington to the one particular tree that became known as the Washington Elm.

It is a verifiable fact that George Washington arrived in Cambridge sometime on the evening of July 2, 1775. He set up his headquarters in a house a quarter mile away from Harvard’s campus. That house, later occupied for years by poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, is now a National Park Site. General Washington spent nine months in this headquarters, which “began his transformation from a Virginia gentleman to the key nationalizing figure of the Revolution and the Early Republic,” according to the National Park Service.

However, NPS reports now suggest that Washington formally took command of the Continental Army at some point on the evening of July 2. The following day, July 3, was his first day in Cambridge, which he spent introducing himself to the Army and inspecting the troops. “Over the nineteenth century,” an NPS report explains, “descriptions of Washington’s first full day in Cambridge gradually became more elaborate, with the commander-in-chief reviewing the full army — or a large portion of it — on Cambridge common.” In reality, he did this inspecting in several small groups. There was no large ceremony under a tree.

The ensuing controversy caused quite an uproar among the tiny circle of Cantabrigian historical aficionados in the early 20th century. Those who loved the Washington Elm’s legend clung to the myth.

Watson Grant Cutter, the vice president of the Cambridge Sons of the American Revolution, took it upon himself to write out his entire family history in a 10-page bound book — still available in Harvard’s Widener Library reserves — concluding that the words on the tablet were true based entirely on his family’s oral history. His primary piece of evidence was a letter from his aunt saying that the community gave “no thought of questioning” the legend, and therefore it was true.

Not to be outdone, the crowd that wanted to prove that the Elm’s story was fake decided to up the ante.

In 1925, Cambridge resident Samuel F. Batchelder wrote to the White House, urging President Coolidge to “blast fiction with facts” and clarify the Elm’s status as a falsehood during his forthcoming July 1926 address commemorating the 150th anniversary of Washington’s taking command.

Remarkably, President Coolidge responded. He declined “to enter into such a controversy,” the New York Times reported. In his speech on July 3rd, 1926, Coolidge made no reference to the Elm at all. The legend would live, at least for a little longer.

Eventually, of course, the truth won out. Every historian that spoke with the HPR said that the Elm’s legend is indeed a myth.

Deep Roots: Reflecting on the Elm’s Meaning

The Washington Elm was important even before the founding of our country, was the center of Cambridge for at least a century and a half, had its progeny propagated all around the nation — and then was completely forgotten. Why?

Was it forgotten because the original tree is dead? That may be a part of the reason. However, the Elm continued to hold outsized influence after its death, including the propagation frenzy of its descendants and the gifting of its pieces to dignitaries. The tree did not lose prominence immediately following its death.

Moreover, the tree still appears intact based on the signs in Cambridge Common today, so its death seems less physically important today than it may once have been. None of my classmates who were familiar with the present tree were even aware that the original was dead.

Was it forgotten because its story is fake? I don’t believe so: If the other, more famous legend about Washington and a tree (the old cherry tree, of course) proves anything, a tree need not be real to become an important piece of American history. Even though the so-called “Washington Elm” did not actually play a part in Washington’s taking command of the Continental Army, the tree incorrectly identified as the Elm remained important until the early 20th century because other people thought it was important.

Has Washington’s influence as an icon faded from our national memory? This seems unlikely, since his estate at Mount Vernon averages a million guests every year, making it the most popular historic estate in the nation. Washington himself also remains the most popular Founding Father.

Greater Boston is absolutely saturated with historic sites and monuments; have we been desensitized to the Elm’s legend by living among so much other rich history? At first glance, this theory sounds plausible. A friend of mine once lived a block away from a hidden Revolutionary-era grave for British soldiers for almost three months without realizing it.

However, this saturation has been true for generations of Bostonians. It makes no sense that we’d only be overwhelmed by our Revolutionary history now.

Instead, there are two other reasons that seem most likely to me.

First, the type of nationalism that the Founding Fathers invoke has come into question. As Americans have come to terms with the racism and oppression inherent in our history, many have begun to reject the “Great Man” theory of history, the idea that a few “Great Men” are responsible for most events. Instead, historians have focused more attention on the role of larger structural forces and traditionally untold voices.

This movement is particularly strong in Cambridge. In fact, the 118-year-old Cambridge Historical Society recently rebranded itself as History Cambridge in an effort to become “less stuffy, less exclusive, and embrace more of the history of all of Cambridge,” Program Director Beth Folsom told the HPR. The organization’s new informal motto, Folsom said, is that “Everyone’s an expert on their own Cambridge history.”

Indeed, the idea of venerating Washington becomes far less appealing when one considers his status as a slave owner and a fierce elitist. Washington’s complicated identity and moral standing may help explain why many Cambridge residents demonstrate less enthusiasm toward Washington’s history at the tree.

Second, Harvard may overshadow the Elm in today’s America. As college admissions have become more competitive over time, increasing numbers of high school students and parents have started to tour universities. Harvard has become a landmark unto itself, and the university’s landmark status may have replaced the Elm’s noteworthiness.

The timing of this model is somewhat accurate: the Harvard Visitor Center opened in 1962, just a decade after the Crimson’s last mention of the Elm, to cater to the increasing numbers of tourists who come to visit the University along with prospective students. Today, thousands flock to Harvard’s campus every day — and almost none visit the Elm.

That said, both of these theories fail to explain why the Elm completely disappeared from Cantibrigian consciousness. One can be skeptical of President Washington without disavowing the significance of a historical landmark like the Elm — even if the landmark is fake. Moreover, today’s tourists could just as easily want to see both Harvard and the Elm on a trip to Harvard Square.

All told, it appears that there’s still no perfect explanation for why the tree has faded from memory. The true cause of the Elm’s disappearance may never be fully known.

—

Despite its disappearance from contemporary consciousness, I was reminded of the tree’s importance upon returning to its site.

Cambridge Common is still the gravitational center of Cambridge’s history. New monuments have been added several times over the last few decades, including a monument to the Irish Potato Famine in 1997.

Most importantly, a memorial to Prince Hall, an African-American leader during the Revolutionary era, was dedicated in 2010. Hall pointed out the hypocrisy of a war waged for independence by people who kept others enslaved. The memorial to Hall was placed right next to the new Elm, a reminder of the ways that the founders of this country failed to live up to their ideals. The memorial’s symbolic location, and its wonderful design, are powerful.

The Hall memorial reminded me that the history of the Revolution is still baked in our nation’s DNA, whether we think about it or not. We’d do well to embrace this history, remember it, and learn from it.

As much as we try to ignore the past, its roots run deep.