This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

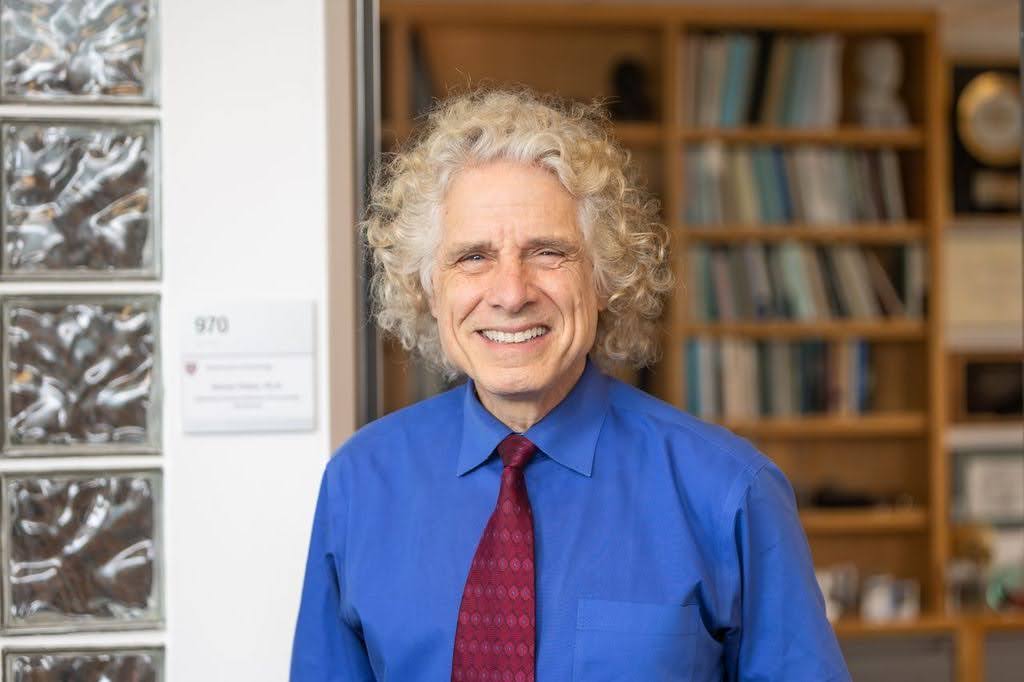

Professor Steven Pinker is the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology at Harvard University and was named one of TIME’s 2004 “The 100 Most Influential People in the World Today.” He has been an outspoken critic of the pro-Palestinian campus protests and Harvard’s response to the Hamas-led attack on October 7th. Pinker sat down with The HPR to discuss his views on the protest restrictions on free speech, institutional neutrality in the aftermath of October 7th, and the administrative reaction to the pro-Palestinian encampment.

Harvard Political Review: In a 2023 interview with the New York Magazine, you agreed that a multitude of your colleagues “share your viewpoints but don’t speak out as publicly as you do.” What would you say are the main factors holding faculty back from speaking out about the war in Gaza? And what can be done – if anything – to reduce the barriers preventing them from taking a more public stance?

Steven Pinker: Well, my comments weren’t specifically about the war of Gaza, but just on academic life in general, where surveys show that large proportions — sometimes majorities — of both professors and students are reluctant to express opinions. The cause is the fear of consequences that can range from censorship to outright dismissal. There are many instances documented by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, so the fears are not ill-founded. And the remedy would be to establish a policy that professors and students are entitled to express controversial opinions. They’re called on to defend them. They may have to defend them against criticism. They [the students and faculty] don’t have a freedom against being criticized, but they should have a freedom against being censored, punished, or intimidated with defamation and unfounded accusations of bigotry.

HPR: In the recent past, can you recall any specific instances of censorship at Harvard or at other universities that were related to the Israel-Palestine conflict?

SP: I’m not talking about the Israel Palestine conflict, and I did not say that there were instances of people who were censored for talking about the Israel-Palestine conflict. I was talking about academia in general.

HPR: This past year, the Foundation of Individual Rights and Expression ranked Harvard last in its 2024 College Free Speech Rankings. Even before the publication of those rankings, you led the formation of the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard. Why do you believe Harvard scored abysmally for its campus speech climate? And what action steps have the Council on Academic Freedom implemented or planning to implement to improve this?

SP: I don’t take the last place finish literally — the counting and the scoring are not that precise — but it does indicate that there is a problem. Even if Harvard were in 20th-to-last place or 40th-to-last place among almost 200 universities, it would be an abysmal showing. The ranking came from a combination of a number of incidents, such as the disinvitation of the feminist literary scholar Devin Buckley because of comments that she had made about transgender women being housed in women’s prisons, the hounding of Carole Hooven and the false accusations that she was a transphobe based on comments that she had made in an interview that, biologically speaking, there are two sexes, the attacks on Tyler VanderWeele and calls for boycotts of his classes and for him to be fired based on the discovery that he had co-signed an amicus brief in 2015 against the Obergefell decision to make same-sex marriage legal in all 50 states, as well as surveys among undergraduates saying that a majority of them felt that they did not feel free to express their opinions in class, and paradoxically, a large proportion said that they would be fine to use force to shut down a speaker — so it was a combination of a number of incidents with the survey results.

The Council on Academic Freedom is devoted to three goals: Academic freedom, civil discourse, and viewpoint diversity. We have been involved in a number of activities. We have sponsored public events in which the concept of academic freedom and its various implications are discussed and debated. We have pushed behind the scenes for meeting with university leaders to express widespread opinions on institutional neutrality, which, just the week before the last, was adopted as a Harvard policy under the name “Institutional Voice.”

Likewise, we have expressed our concern about mandatory diversity statements in hiring for faculty positions. And, a couple of days ago, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences announced that they would no longer require them for job applicants. We have expressed letters of concern over the non-enforcement of regulations against heckler’s vetoes — that is, protesters who disrupt events to prevent speakers from expressing their views, or invade a faculty-student dinner against regulations on time, place, and manner of speech. We have consulted with individual faculty members who have felt that they’ve been persecuted, for example, in climate surveys that are vague ways of discrediting faculty member without any specific charges, such as harassment or bullying.

HPR: In the past, you have criticized Harvard for not doing more to uphold the First Amendment, and you have argued against criminalizing “deplorable speech” such as hate speech. However, you have also written that Harvard should have shut down the pro-Palestinian encampment, which encampment organizers defended as a peaceful exercise of free speech. How do you reconcile those two viewpoints?

SP: Oh, because free speech doesn’t mean that I get to break into your apartment and spray graffiti on your walls, or to stand outside your apartment with a sound truck blaring propaganda at 3 a.m. First Amendment jurisprudence has long recognized that free speech is not a license to use force to break the law nor to infringe on other people’s rights. And so restrictions on time, place, and manner have always been tightly interwoven into defenses of free speech, otherwise they could collapse in absurdity. For example, if a professor offered to trade grades for sex to a student, he would not be able to defend himself on the grounds of free speech. Or if someone threatens to kill someone, that too would not be protected under the First Amendment or any reasonable definition of free speech. So both crimes are inherently committed through speech, like extortion and harassment.

Reasonable restrictions on time, place, and manner, have always been a part of defenses of free speech. Now, restrictions on time, place, and manner themselves have to be carefully delineated and defended; otherwise, they could be a pretext for suppressing speech. And the usual threefold test is: Are they content-neutral? That is, do they apply regardless of what the protesters are actually saying? Are there alternative means by which those opinions can be expressed? And is there a rationale for the restrictions? That is, do the restrictions serve some legitimate institutional purpose? In the case of the encampment, the argument for shutting it down passes all three time, place, and manner restrictions. Namely, it has nothing to do with the content of what the protesters are saying, although I think the content is deplorable, but that’s not by itself a reason to shut it down.

Do the restrictions serve an institutional purpose? And the answer is clearly yes. Blaring music and slogans chanted over bullhorns interfere with the ability of students to study and administrators to do their jobs. By expropriating university commons for a partisan cause, they [the protestors] brand the entire university as seemingly complicit with that particular opinion, as opposed to alternative opinions. For example, flying a Palestinian flag from the Harvard flagpole or putting a keffiyeh around John Harvard tells the world that Harvard is sympathetic, if not in agreement, with one particular viewpoint, despite the fact that many people at Harvard vehemently disagree with the protesters.

And are there alternative means for the protesters to express their opinions? Well, sure, they could hold signs, they could pass out leaflets, they could screen films, they could hold public events. There’s no shortage of ways of expressing their opinion that fall short of actually taking over areas of the university that belong to everyone and commandeering them for their own particular cause, which many members of the Harvard community disagree with.

HPR: In an article for The Boston Globe, you named examples of alternative actions that student movements could take, including “write articles, post manifestos, hold events, show films, or request meetings with university leaders to make their case.” Pro-Palestinian students have carried out these actions multiple times. However, the Harvard Undergraduate Association indefinitely postponed a student referendum about Harvard’s investments in the West Bank, the administration refused multiple times to meet with Harvard Out of Occupied Palestine, and the university suspended the Harvard Undergraduate Palestine Solidarity Committee. How would you recommend that the pro-Palestinian movement protests Harvard’s involvement with the Israel-Palestine conflict and effectively communicate their message?

SP: The right to protest doesn’t mean the right to coerce — that is, if Harvard does not agree to their demands, then Harvard doesn’t agree to their demands. You can’t always get what you want. You can make your case, but you do not have a right to coerce people into acceding to your demands or agreeing with you. You have a right to make your case, and other people have the right to disagree with you.

Now, the suspension of the Palestine Solidarity Committee is something the Council on Academic Freedom actually looked into. Rakesh Khurana, the Dean of the College and who made that decision, he made the case that this was viewpoint-neutral. That is, Harvard had regulations against student groups affiliated with outside groups, and that it had been applied to other student groups, and that there was also a moratorium granting university recognition of student groups, which also applied, by the way, to an undergraduate affiliate of the Council, the Harvard Undergraduates for Academic Freedom. And they too were told that they were not allowed to declare themselves a Harvard group for the time being. So that was a matter of concern.

I guess it’s impossible to prove that it was viewpoint-neutral, but Khurana made the case and we’ve found no reason to challenge that case. But I think that the students can reasonably request meeting with university officials, and, in fact, they were eventually granted one. They met with Alan Garber. But if the idea is well, “you didn’t do what we said, so we have the right to continue to make campus life miserable until you accede to our demands,” then the university has a reasonable case for saying “no, we cannot be coerced.” You can make your best argument, but if you fail to convince people, then that does not give you the right to try to coerce them and to accede your ultimatum.

HPR: Shortly after the end of the encampment on May 14, the Administrative Board placed at least 35 students involved with the encampment under academic sanction, including thirteen seniors who were barred from graduating. Vetoing their decision, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) voted to let the 13 seniors receive their degrees, but the Corporation overruled FAS’s decision. How do you view this disagreement between the Harvard administration, FAS, and the Corporation? What implications and significance, if any, do you think the Corporation’s dismissal of FAS’s decision holds for the faculty’s right to academic freedom?

SP: It doesn’t seem to me it’s the faculty’s academic freedom because they weren’t expressing an opinion, although it could be relevant to the students’ academic freedom. I think a lot would depend on the facts of exactly what the infractions were against the students, of whether they violated regulations that were already on the books, and whether the Faculty of Arts and Sciences has the jurisdictional right to overrule the Board. And I’m not up on all of those facts, some of which have not been made public. I think the general point, though, is that disciplinary proceedings ought to be far more transparent and open. I think Harvard probably overinterprets the FERPA Act and probably keeps disciplinary proceedings, both against students and faculty, more confidential than they have to.

I think they ought to be brought into the open both to ensure that there are no miscarriages of justice and to also serve the purposes of discipline, one of which is to deter illegal behavior by others. So the answer to your question is, it really depends on a lot of the facts that I don’t think are out there. I think that if those particular students specifically breached university regulations, and if university regulations say that you may not receive a degree if you have been reprimanded, then that would be okay. But if it was an ad hoc decision and it was not principled, then that would not be okay.

HPR: On January 2, former Harvard University president Claudine Gay announced her resignation following an arduous period of backlash over Harvard’s response to the Hamas-led attack and her testimony at the congressional hearing on antisemitism. What are your thoughts on her resignation? And from your perspective, how could she, as well as other university leaders, have responded, if at all, to the conflict and the tensions on campus?

SP: Well, it was a complex case, but I think she attracted too much blame for conditions that were not under her control. For example, her notorious answer to the question “would a student who advocated genocide be punished under campus speech codes?” She correctly answered — that they would not be because Harvard does respect the freedom of speech, including advocacy of violence, as long as it’s not incitement to imminent violence. On the other hand, the response looked ludicrous, simply because Harvard had such a dismal policy of respecting free speech rights before her testimony. So, in the face of the most egregious case imaginable — advocating genocide — she became a First Amendment absolutist. In the context of Harvard actually punishing and shutting down far more innocuous speech, it was a regrettable performance, but it was in the context of Harvard’s dismal track record, that it looked so ridiculous.

Let me just backtrack: Another problem is that a lot of the heat that she attracted came from the statements that she had made following October 7th that seemed to be too late and too wishy-washy. This is one of the rationales for a policy of institutional neutrality, or, as Harvard calls it, “Institutional Voice.” Mainly, when university officials are called on to make statements, inevitably they will offend some portion of the university community, which is why they should get out of the business of making those statements in the first place. And if Harvard had had a policy of institutional neutrality at the time, then she would have been off the hook, because you could just say, “our office just doesn’t do that.” Without such a policy, the failure to issue a statement was itself a statement that got her into trouble, and that was another example of something that she was blamed for. That was part of the institutional culture at Harvard before she even assumed the presidency.

Now, that’s completely separate from discoveries of plagiarism. And that was a problem in the sense that even though the acts of plagiarism that she did commit were, I think, rather minor, nonetheless, they would have gotten one of our students expelled. I mean, I’ve seen it happen. And so it was untenable to have the president of a university violate policies that — in the case of students — would have led to severe consequences. It would make it very hard to enforce Harvard’s own policies on plagiarism. That was completely separate, of course, from her congressional testimony or the statements that came out of her office.

HPR: Since you started teaching at Harvard in 2003, this campus has witnessed multiple other protests and occupations associated with the pro-Palestinian movement and other movements. From your perspective, what do you see as the main differences between the Pro-Palestinian protests and encampment and previous campus protests?

SP: Well, I personally think that the restrictions have been enforced in previous campus protests such that the policy was applied in a content-neutral manner. I wasn’t at Harvard at the time, but if I were I would say that they should have enforced the rules precisely because their failure to enforce might be seen as a precedent to all manners of protest, including increasingly disruptive ones. Now the question is, does the past squeamishness on the part of university officials and the president set a precedent that ought to be enforced in perpetuity? I think probably not.

There may have been extenuating circumstances at the time. I believe that President Neil Rudenstein was about to leave office, and he didn’t want to create a huge scandal just days before leaving. So he kicked the can down the road, and it seems to me that that shouldn’t be seen as binding the university till the end of time. That if it was a mistake not to enforce them then, then as long as there is a policy going forward that will be enforced in a content-neutral way, then that’s what the university has to do. It can’t be bound by every mistake or weaseling out of a difficult decision that predecessors may have done in the past.

HPR: You mentioned content-neutral protest regulations, are there any other regulations that you think were enforced for past protests but not for present ones?

SP: I don’t think my knowledge of Harvard history would be deep enough to answer that question.

HPR: How would you describe the health of the dialogue and the discussions around the war between Harvard affiliates with different perspectives? Do you see the balance of dialogue as evenly distributed between pro-Palestinian, pro-Israeli, and other perspectives, or does it shift in a particular direction?

SP: I think it’s not good, there’s a lot of misinformation and blurring of issues. For example, the humanitarian case against the way in which the war has been waged by Israel, which has been completely conflated with whether the state of Israel should be wiped off the map. The protesters had slogans like “from the river to the sea,” and they showed maps of Israel with all of the Israeli cities obliterated and replaced by Arabic names. This is with no discussion whatsoever of what a single state in the Israeli territory would look like. What would happen to the 7 million Jews who currently live there? Would they be expelled? Would they be massacred? Would they live as a Jewish constituency in an Arab state — something that does not exist anywhere in the world? Would it be a democracy? Would it be a theocracy run by Hamas?

The fact that students at the world’s most famous university are pressing these demands without any kind of explanation as to what their case consists of speaks to a failure of the intellectual quality of the dialogue. As are various sources of misunderstandings, such as prior to 1967, Gaza and the West Bank were not part a Palestinian state, they were actually controlled by Egypt and Jordan, respectively — facts that seem to be lost in the protests.

And on the other side, I think there are legitimate criticisms of the way that Israel has been waging the war in Gaza. Do they have a plan for what would happen if they managed to defeat Hamas? Who would actually run the Gaza territory? What would be the long term viable arrangement, both in the West Bank and Gaza? Those questions though are very often raised in editorials in The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Ironically, that kind of debate is not what has been carried on with the anti-Israeli protesters. It’s a blanket denial of the possibility that the country should exist with no discussion of what that act would actually imply for the millions of people living there, or what the state would be.

So I think it would be extremely valuable if Harvard had more events or dialogue on the history of the Arab-Israeli conflict, fact-checked people making arguments on both sides without calling for the elimination of the other. Perhaps a model for that is the set of events that Tarek Masoud at the Kennedy School has had over the past year, where he has grilled advocates on both sides of the debate, pressing them to justify their views. I think what Tarek did was admirable, and we definitely need more of it.

Senior Culture Editor