According to the staff of the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the phrase “White nationalist” is relatively new by linguistic standards since it only started to appear in print during the first half of the 20th century. The concept of a state by, for, and populated with White people by design, however, is much older within the United States. For instance, the Naturalization Act of 1790 — among the earliest immigration laws in the United States — extended a path to citizenship to “any Alien being a free white person” after a two-year residence while not giving that same path to members of other races. Later on, the Oregon Black Exclusion laws of the 1840s prohibited free Black Americans from entering the northwestern territory, and the Immigration Act of 1917 banned the vast majority of immigration to the United States from Asia. The concept of the United States as a White nation is woven into the earliest legal fabric of its identity. It is by no means a new idea.

What might be legitimately more novel are the attempts to crystallize the U.S.’s role as a White ethnostate, or at the very least to designate part of what is now the United States as such a state. These attempts go further than the restrictive immigration policies of yesteryear. Formal proposals like the Northwest Territorial Imperative or informal propositions like those put forth by the likes of Bradley Dean Griffin, Jason Kessler, and Jeff Schoep are mainstays of the far-right ideology of the present day, but their aims are different than those of before. For them, a White ethnostate is a state founded on their belief in the superiority of and an imagined threat to “Whiteness,” White people, White Christianity, and “the West,” and that anything not sufficiently in those categories is to be denigrated. To quote possibly the most infamous 21st-century White nationalist, at least before his apparent about-face in 2020, Richard Spencer stated in a 2013 interview stated that his vision “is a new society, an ethnostate that would be a gathering point for all Europeans.”

Putting aside the fact that a “unified Western culture” is less of an intrinsic identity and more of a modern invention, a White ethnostate is quite literally a rehashing of Nazi ideology for America. Yet there is more to it than that. It is not just that the nationalistic plans of these people are morally reprehensible. A White ethnostate in the 21st century would fail. And it would fail spectacularly.

Obstacles to Independence

To begin with, founding a White ethnonationalist state on current American soil would prove to be a nearly impossible task. There are, theoretically, two ways by which such a nation could gain legal rights to the land on which to found their country: by legal secession or by force. Legal secession has been argued within the American legal system before, most notably in the 1869 Supreme Court case Texas v. White. By a 5-3 majority, the court’s decision was clear: States cannot secede from the union. No meaningful challenge to that ruling has come up in the past century and a half since it was decided, and it is relatively unlikely that the Supreme Court as it stands today, even with its conservative bent, would be willing to uproot that particular precedent.

A slight variation on the above idea might be a new entrant into the United States that is designed for White people. This would be similar in design to Oregon’s original status, specifically after the Black Exclusion laws were passed. Perhaps this is what Patriot Front founder Thomas Rousseau meant when he wrote, “A nation within a nation is our goal.”

Unlike wholesale secession, the partition or formation of a new state from an existing state within the Union is legal and has precedent, with examples like Vermont, Maine, and most notably West Virginia, provided that there is the “Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.” However, such a plan would necessitate a change in legislation to allow stronger borders between states, which is unlikely to be approved today as it would violate Supreme Court precedent, and getting Congress or any individual state on board with this plan is equally implausible.

A White supremacist may argue that “nations within nations” already exist in the United States in the form of Indigenous nations and reservations, which are treated as somewhat separate entities from the U.S. federal system. However, there is a difference in kind here. The Indigenous nations were not newly established states with the intention of excluding outsiders by design; they are better understood as legal recognition of preexisting nations that existed on the American continent before the U.S. was founded. It is difficult to argue that an exclusionary construction should be treated with equal sovereignty to a marginalized nation, especially predating the United States.

That leaves the option of taking the land for a White ethnostate. True, there are military aspects to many White nationalist organizations, but trying to fight the U.S. military in any capacity on home soil is a nearly insurmountable task. It is quite literally playing with fire; the state could not be founded by force.

Obstacles to Success

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that the barriers to creating the White ethnostate described above are surmounted. Let us suppose that through some means, whether rhetorical, legal, or martial, a White ethnostate is founded on American soil. Even if we waive all these issues, the state in question would still fail.

To begin with, an ethnostate of this design could not live up to the economic power and productivity of the previous United States. It is a well-documented fact that a significant portion of the U.S.’ economic prowess and growth can be ascribed to the amount of immigrants we let in, the vast majority of whom are people of colour. From the very beginning, the United States’s economy was built on the backs of immigrant and native-born people of colour, and to eliminate non-White people is to make a huge economic mistake which will have devastating effects on the proposed ethnostate finances.

Furthermore, a state of this design would not only struggle to get on its feet economically — especially if it is trying to replicate the U.S. — but also it would likely struggle to receive the aid and collaborations of other nations as well. The United States would be in direct opposition to such a state and would exercise its power as such, just like it did during the Civil War to the Confederacy. This fact, combined with a foundation of such uniquely racist principles, would likely result in the state being virtually unrecognized by the international community as a whole, specifically by the United Nations.

The State’s Mission is Its Own Worst Enemy

Beyond the political fallibility of such a project, it is important to recognize that the culture of a White ethnostate within America would sow the seeds of its own collapse as well. Central to the beliefs of White ethnonationalism is a sense of White supremacy and racial purity; after all, what is the point of creating a state for White people if White people are not something to be cherished? It was David Eden Lane, popularizer of the Northwest Territorial Imperative plan for an ethnostate, who argued, “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for White children.” In such a state, Whiteness, unsurprisingly, must be protected, in this case from a perceived threat of extinction, at all costs.

A movement and a nation built on the exclusion of the other must always find new others to exclude. When the “us” in an “us vs. them” mentality is something as nebulous and frankly modern as “Whiteness,” this constant search for the “other” can prove self-destructive. When the original other is expelled, the energy is pointed at those deemed “not sufficiently White.” In the past, such groups have included Jews, Irishmen, Italians, Catholics, and so on. Eventually, such a state becomes an ouroboros: A snake that eats its own tail until nothing is left and the ethnostate collapses under the weight of its own struggle for purity.

White ethnonationalism is more than just an ethical nightmare. It is an idea that, if attempted, would face incredible obstacles at every single turn. The legal, financial, national, and systemic issues that would plague such a proposal outweigh the current ability to implement that proposal. We must remain vigilant, but in the grand scheme of racism in America, this particular facet is not likely to go far.

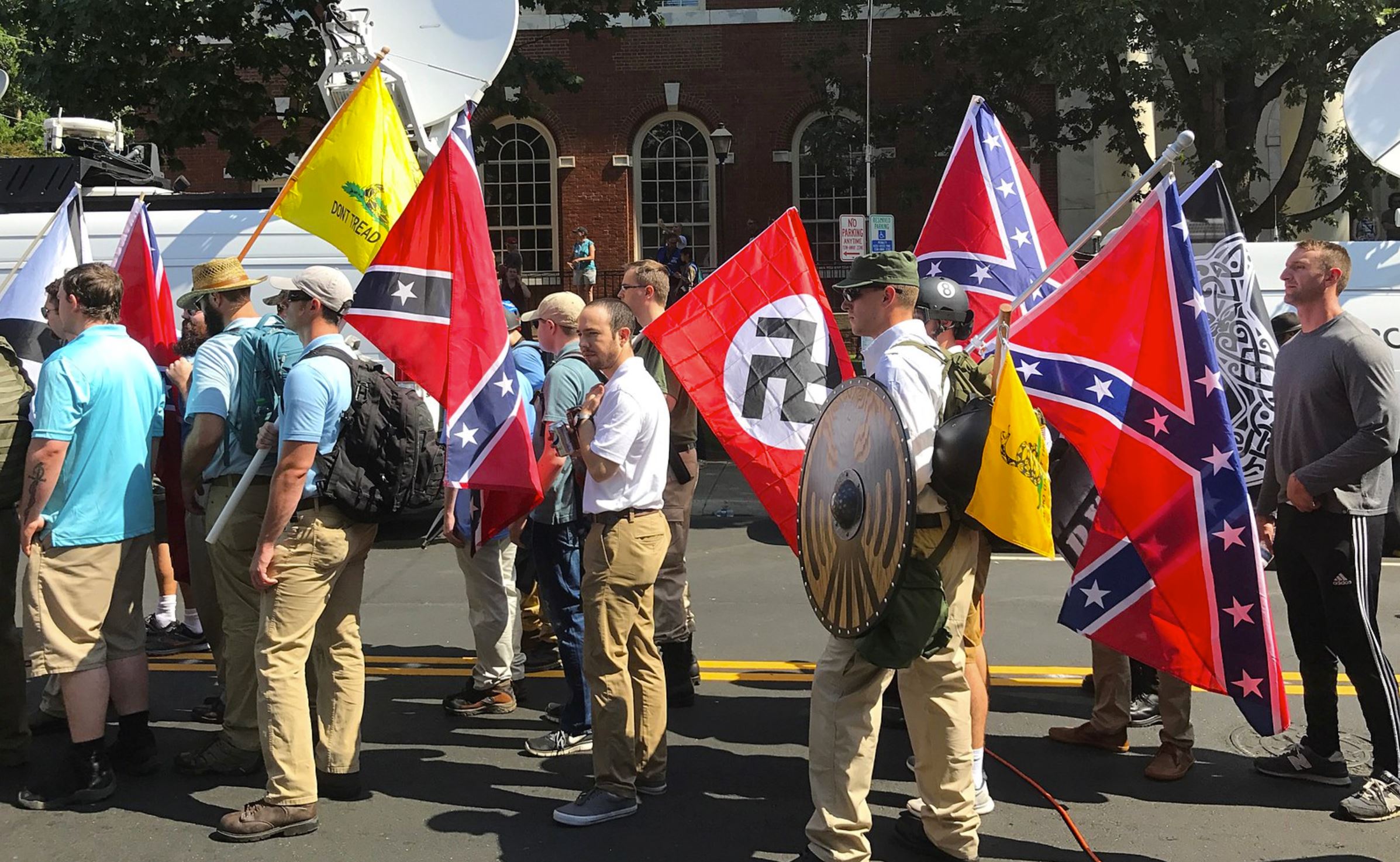

Image Credit: “Charlottesville ‘Unite the Right’ Rally” by Anthony Crider is licensed under CC BY 2.0