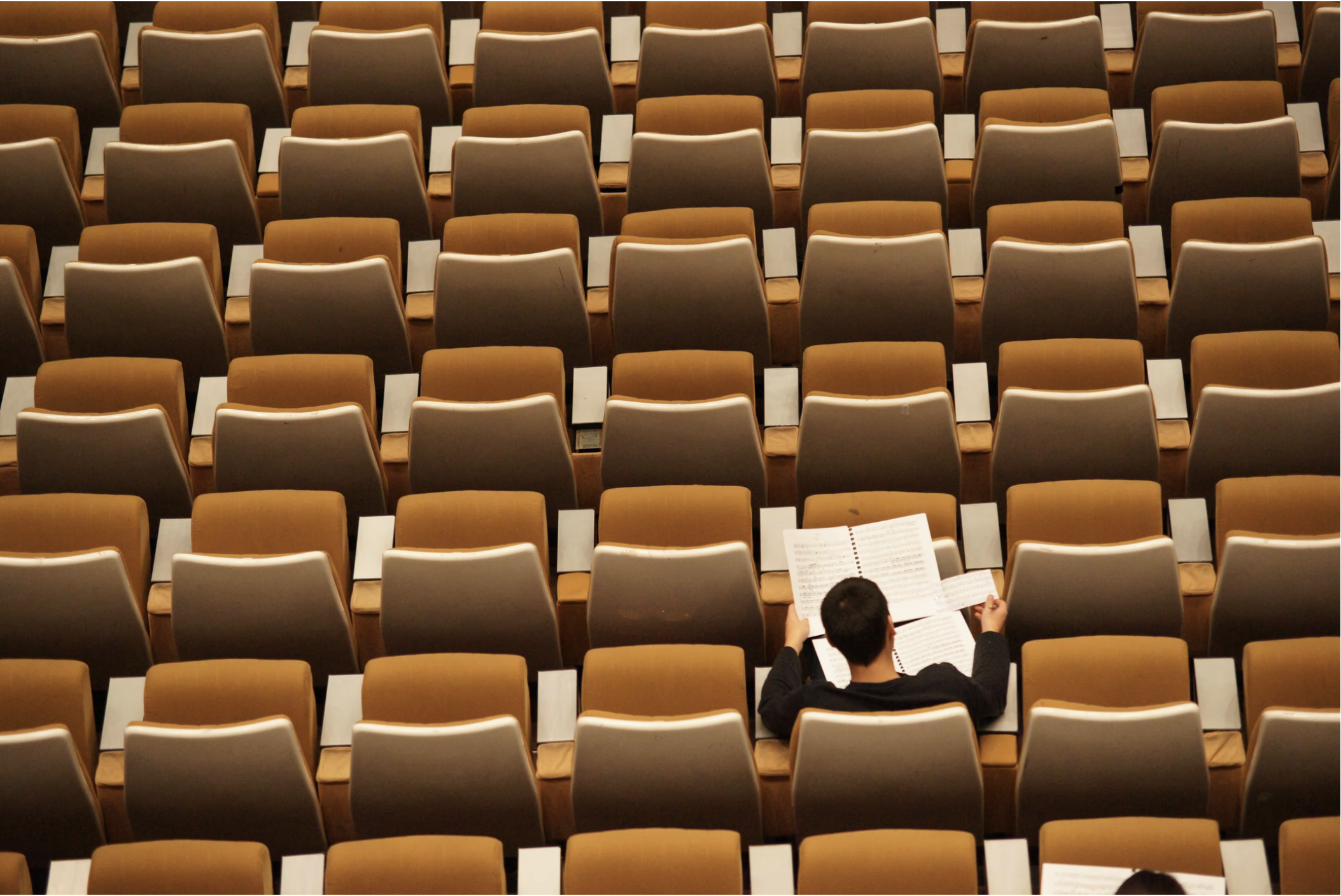

As an influx of undergraduate students poured into Cambridge in August, Harvard celebrated the on-campus return of its majority-vaccinated undergraduate population. Well into our first semester of fully in-person instruction since March of 2020, campus life has now been revitalized in full force. With a bustling activities fair, packed lecture halls, and a variety of athletic and social events, my first semester of college has felt remarkably normal thus far. Though I am grateful to have a relatively stable on-campus experience during my freshman year, I have often found myself troubled when hearing friends say things like “Now that the pandemic is mostly behind us…” or, “since things are starting to get back to normal…” and, “in our new post-pandemic world…”

COVID-19 infection rates may be declining on campus, but beyond the Harvard gates, the pandemic is far from over. With the Delta variant gaining traction around the world, along with the persistence of vast disparities in vaccine access between higher and lower-income countries, the pandemic has already taken more lives this year than it did in the entirety of 2020. Although Harvard has implemented a variety of excellent pandemic safety protocols — including required vaccinations, frequent testing, and an indoor mask mandate — make no mistake: we are not immune to the dangers of the coronavirus, and some members of our community are at much greater risk than others.

The word “pandemic” is commonly perceived as a scientific term created to quantify the extent of a disease’s prevalence, but it also bears a subtle narrative arc with a beginning, rising action, conflicts, main characters, settings, climax, and ending. For example, in the case of COVID, many might recall “the beginning” as that week in mid-March when schools closed and Tom Hanks announced that he had contracted the virus. Our memory of the “rising action” is likely to include the onset of panic-buying and nationwide toilet paper shortages. As for the “conflicts” and “main characters,” elected officials sparring over the merits of mask-wearing might come to mind, along with the White House’s daily press conferences featuring budding protagonists like Dr. Anthony Fauci and Dr. Deborah Birx. In terms of “settings” and the “climax,” you may recall witnessing harrowing news footage of New York City streets lined with refrigerated morgue trucks bearing corpses from hospitals at capacity. While there is likely a broad consensus on the contents of each aforementioned point in our pandemic’s narrative arc, our conception of “the ending” has proven divisive.

Today, data displaying falling worldwide coronavirus case rates may offer the impression that the pandemic is coming to an end. However, a fixation on the total number of cases fails to consider that those who continue to contract the virus generally belong to the most vulnerable groups in society. In spite of the fact that COVID has often been hailed as “the great equalizer,” reality has proven quite the opposite. Infection rates and death tolls have disproportionately impacted already marginalized groups, such as African Americans, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, and most prominently, immunocompromised individuals and residents of countries with stalled vaccine rollouts.

While many Harvard students understandably feel eager to experience the full range of in-person social life they missed out on last year, many student gatherings have blatantly disregarded COVID-safety protocols, endangering the most vulnerable members of our community in the process. Despite Harvard’s vaccination mandate, immunocompromised individuals and those yet ineligible for the vaccine are still at extreme risk in the event that they contract the virus. In turn, we all must adopt a greater sense of personal responsibility in the interest of protecting the most vulnerable among us. We must also exercise a far greater degree of compassion and awareness when discussing the wide-ranging impacts of this global tragedy. While some had the privilege to be able to embrace the pandemic as an opportunity to engage in much-needed rest, relaxation, and personal growth, many others among us experienced an unprecedented level of suffering and upheaval.

When contemplating our current crisis, there is certainly no shortage of topics that may prompt fear, concern, and despair. However, the pandemic has laid bare the harsh reality that this global suffering has not been distributed evenly. I understand the value of seeking solace in silver linings during difficult times, but as I hear many of my fellow students praise the pandemic as a gift designed to force us to reshape our values or slow down and step back from the busyness of our everyday lives, I have grown increasingly skeptical of the practice of searching for silver linings in this global catastrophe — one in which suffering has been unjustly distributed, harming racially and socioeconomically marginalized groups the most. When I hear these types of comments, I am often reminded of a poem by Harvard alum Clint Smith, in which he writes, “When people say, ‘we have made it through worse before,’ all I hear is the wind slapping against the gravestones of those who did not make it.” The poem goes on to inform its audience that “Sometimes the moral arc of the universe does not bend in a direction that will comfort us. Sometimes it bends in ways we don’t expect & there are people who fall off in the process.”

More Americans will die from COVID tomorrow than died on 9/11. The same goes for the next day, and if current projections hold, also for the day after that. When you decide to attend a packed, unmasked party, when you decide to take off your mask in a crowded space, when you decide to disregard COVID-safety protocols and shirk your weekly testing cadence, you are making the choice to be a complicit party to each and every one of those deaths. If we believe the pandemic to be over simply because our lives have regained a semblance of normalcy, we may not immediately see the impacts, but the disease will continue to ravage other communities, and the most vulnerable members of our society will once again bear the burden. In the words of historian Jim Downs, “pandemics end when we stop caring about their victims.”

Historically, the stories of infectious diseases have mirrored the longstanding inequities and shortcomings of their social contexts. However, our responses to such outbreaks need not reflect the same attitudes. As we proceed with our first full semester on campus, we must consider what we owe to those who did not make it. Be compassionate. Wear a mask. Stick to your testing schedule. Don’t just do it because it’s required — do it for the people you may never meet, in hopes that they, too, might make it. It’s what we owe to those that didn’t make it.

Image by Philippe Bout is licensed under the Unsplash License.